Unbundled, untied & un-mutualized: The road to fiduciary

One of the biggest trends in the sale of life insurance is the increasing demand for standards of care. Should all life insurance advisors be held to a fiduciary standard? Or is a suitability standard still acceptable? And how did we get to this point? Let’s take a look at the chain of events that resulted in advisors becoming more vulnerable to claims of negligence and bad faith.

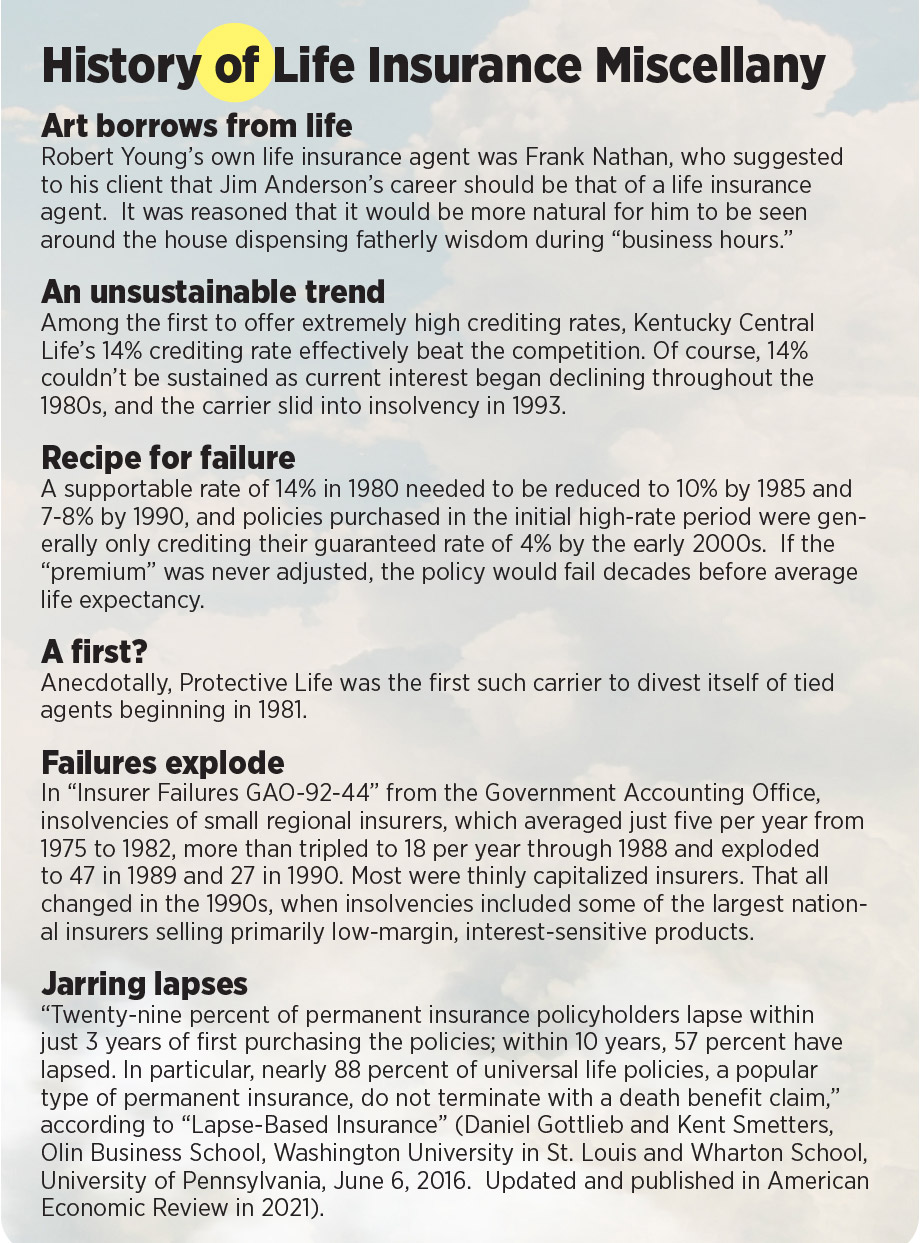

Baby boomers will remember the popular “Father Knows Best” TV series that debuted in 1954. In the series, “Father” was a life insurance agent. Robert Young, the actor who portrayed “Father,” Jim Anderson, on TV gave voice to The American College’s founder Solomon Huebner’s admonition that a life insurance agent should be viewed as a professional, in the same way as a lawyer, accountant, engineer or clergyman. And that’s how Jim Anderson appeared to millions of mid-1950s viewers.

The satisfaction rating of life insurance agents has been in decline ever since.

When you follow the “Game of Life Insurance” path from the first U.S. life insurer, formed in 1759, through the proliferation of proprietary indices used since 2021 to enhance the appearance of indexed universal life policy illustrations, readers can begin to see a pattern of movements forward — and backward — of the issues that increasingly put insurance agents in peril of complaints and lawsuits about their sales actions and activities.

Largely evolving from the 1905-06 New York Armstrong Investigation, the industry had settled into selling life insurance to millions of Americans through industrial insurance (so-called debits involving the weekly payment of premiums with nickels and dimes) as well as through local, insurer-operated life insurance agencies. Those drawn to the industry for a career in insurance sales were vetted, completed a “Project 100,” and if accepted, received product and sales training from the agency — selling only for that insurer. The fictional Jim Anderson was a graduate of the process, as was I when I first entered the industry in 1967 as a senior in college.

In general, there was a strong ethic around prospecting, selling, servicing and compensation, the latter largely supported by compensation in the form of a “55 and nine 5s” commission structure, encouraging post-sale service by the agent who sold the policy. By the late 1980s, there were more than 2,000 life insurance companies in the U.S, but barely 10 years later, the number of carriers had declined to slightly fewer than 750, most often reduced through carrier acquisition or absorption of blocks of in-force policies.

Unbundled: A new development

1978 ushered in the most dramatic paradigm shift the industry had experienced in more than 200 years: the development of unbundled life insurance products. Featuring “transparent” elements of expenses and credits, these current assumption life products (almost immediately renamed universal life) allowed the customer to “pay what you want, when you want.” In the marketplace, this quickly transformed to “pay as little as you want, as infrequently as you want.”

In reflection, this paradigm shift occurred almost exclusively because of two external elements in the late ’70s and early ’80s. There were high interest rates because of an unprecedented level of inflation. This was the period with the introduction of a personal computer and printer that could display the extremely low calculated “premiums” one could pay when a 14% crediting rate was projected over a lifetime (yet, only momentarily sustained).

Before the UL Pandora’s box was opened with current assumption designs, whole life policies — with their guaranteed premiums on cash values, and death benefits — didn’t require a policy illustration to convince the customer to buy. UL, on the other hand, was sold almost exclusively via a printed policy illustration that took, for example, the current crediting rate of 14% and used that rate to calculate the resulting cash value accumulations and the premiums to sustain the policy — to age 95 or 100. Few agents (and still fewer customers) recognized the fatal flaw of policy illustrations: Instead of sustaining for the next 40-60 years of average life expectancy, the current crediting rate would almost immediately begin falling (declining to the typical 4% guaranteed rate by the early 2000s).

Regulators would later require the term “premium” be used to describe the illustrated contribution to support the policy out of fear that agents would otherwise call it an “investment.” Billions of dollars were disgorged by the industry through class action lawsuits in the early to mid 1990s, in large part due to the industry’s failure to understand and communicate how the policies really worked.

Undone: Policies lapsed or were replaced

Roughly five years after UL was introduced, the percentage of new whole life policies in the marketplace had plunged from mid-40% (the rest was term insurance) to 18%, and UL had escalated to achieve whole life’s former status as the biggest “seller” of lifetime death benefit products. Although this unprecedented level of disintermediation could have made sense to many consumers who weren’t interested in paying any more for their life insurance than they had to, declining crediting rates would cause many (if not most) policies to lapse or be replaced — due to projected policy failure long before life expectancy.

Untied: Training and supervision suffered

In part because of UL’s much lower profit margins as compared to those of the industry’s mainstay whole life products, prominent carriers as early as 1981 began withdrawing from the decades-old system of “tied agents” and local insurance agencies.

The unintended consequences of untying would have an enormous impact on “ethics” in the sale of life insurance. Training — and especially local supervision — were often the first benefits to be lost as more and more carriers divested themselves of the “agency system.” The process of untying product “manufacturing” from distribution was accelerated in the late 1990s by such carriers as Transamerica, Pacific Life and Franklin Life.

Unexpected: String of carrier failures

While there had been at least one notable carrier failure in the 1980s, many in the industry were shocked to learn of the July 1991 failure of Mutual Benefit Life, which was founded in 1845. This failure followed the failure of the less-traditional Executive Life just a few months earlier. The dominos continued to fall as the industry experienced the failures in 1994 of Confederation Life, Monarch and Kentucky Central.

Where did the agents go? The new industry of general brokerage agencies was greatly enhanced by agents (now independent brokers) seeking a “home” for sales support, access to multiple insurers, and especially high, negotiated commissions.

Some distressed carriers were able to avoid the pain and notoriety of failure by being acquired by other companies. The largest of those occurred when The Equitable became AXA in 1991 (not a good year for the industry).

Mergers included MassMutual absorbing Connecticut Mutual; the merger of Home Life with Phoenix Mutual; MetLife acquiring The New England and, later, GenAmerica (which included General American Life); Prudential’s reinsurance treaty with The Hartford; and MassMutual’s acquisition of the in-force policies (and many career agents) of MetLife’s U.S. individual life operations.

On the “plus” side of all of this, the existence of state-run guarantee associations ensured that death claims (and annuity payments) were able to continue, even in the face of unprecedented financial stress on some life insurance carriers.

Unmutualized: Transformation to publicly owned

In this saga of the devolution of the life insurance industry, the other shoe was dropped when life insurance companies that dated back 150 years or more shed their identities and operating procedures as mutual companies and transformed themselves into publicly owned companies.

Some of the biggest (remaining) names in the industry joined the trend: Prudential, MetLife, SunLife of Canada, John Hancock, Union Mutual, Phoenix and Principal all began focusing on the needs of the shareholder above the exclusive needs of the policy holder — the intended focus of mutual carriers. Other demutualizations ended in the outright disappearance of several carriers, including Central Life, Royal Maccabees and Provident Mutual.

When I became a life insurance agent in 1967, I was told that “mutual” was the way God intended life insurance! Something valuable has been lost in the ensuing years.

The transformation from death benefits to “§7702 Plan” sales illustrations promising tax-free income far in excess of earlier contributions to “the plan” is just one more way the life insurance industry of Solomon Huebner’s era has strayed from the primary duty to protect widows and orphans from economic ruin.

Add premium financing to the proposals promising “free life insurance” and, we assume, free retirement income. The result is potentially disastrous for the clients.

Understanding: Unrealizable promises

With the preceding narrative as context, it is not difficult to draw some important and informative inferences. Products transformed from guarantees to unrealizable promises in the late 1970s. Also during this time, the method of selling those products became largely based on policy projections that were inherently unable to measure the effect of the subsequent rise and fall of in-force crediting rates for UL, variable universal life and IUL.

Acknowledging that life insurance companies needed to stay profitable, they managed this by divorcing their tied agents, leaving those agents to join brokerage operations that were often unskilled in the training and supervision the industry previously provided to maintain high standards of market conduct.

Carriers demutualized or were absorbed into bigger companies (or simply failed). In the face of still-falling interest rates, the remaining carriers devised newer and more complex methods of attracting customers.

Compensation methods changed as well, often allowing a broker to be paid all the compensation they would ever receive for the sale of a policy “heaped” in the very year in which it was sold (disincentivizing policy service by the broker after the sale) and at commission levels “above street.” As far as it went, one could say that the industry stayed flexible and largely managed to survive a very stressful 40 or more years of economic change.

Unfortunately for those of us who have “seen it all,” much has been lost, and those losses have been particularly hard on clients. In an academic paper first published in 2016 and then updated in 2021, research conducted by professors Daniel Gottlieb and Kent Smetters of Washington University and The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania observed that nearly 88% of all UL policies ultimately would not sustain to the point of paying a death claim.

In those instances, any “gain” realized in the surrender of a policy would sacrifice the long-touted promise of tax-free accumulation and distribution of life insurance cash values.

Meanwhile, any gains would become immediately subject to ordinary income taxes — never mind the loss of the “inevitable gain of the life insurance policy held until death” — when a policy doesn’t fulfill that original intention.

The lifetime relationships pursued by the Greatest Generation’s Jim Anderson have today become largely transactional and “what have you done for me lately?” And in an often-used metaphor, the chickens are coming home to roost with an increase in civil and even class action lawsuits against agents and carriers.

As can be seen from the “Game of Life Insurance” timeline below, there are times of progress in the pursuit of client best interest and suitable sales — but also times where those aspirations are in decline. The efforts of The Society of Financial Service Professionals, the Certified Financial Planning Board, the New York State Department of Financial Services, the Department of Labor, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority have attempted to emphasize serving a client’s best interest and only recommending suitable products — those two standards sometimes positioned as a “fiduciary” duty.

When taken in the context of the 115 years since the start of the modern life insurance industry, there is progress.

Regulators regulate, but rules easily can be bypassed without a commonly agreed-upon ethos. The financial services industry’s awkward and tenuous move away from caveat emptor and toward fiduciary standards of care is a natural reaction to the issues reviewed herein. Let’s hope the efforts of these entities will prevail. Our clients are counting on us.

Richard M. Weber, MBA, CLU, AEP (Distinguished), is a 57-year veteran of the life insurance industry, having been a successful agent, a home office executive, a software designer, author of four books and more than 400 published articles, and an educator. He is the co-creator of Certified Insurance Fiduciary, an online program for advisors wanting to enhance the scope of their advisory services. He may be contacted at [email protected].

Who will benefit from prescription drug price regulation changes?

Not Your Parents’ Senior Market

Advisor News

- Mitigating recession-based client anxiety

- Terri Kallsen begins board chair role at CFP Board

- Advisors underestimate demand for steady, guaranteed income, survey shows

- D.C. Digest: 'One Big Beautiful Bill' rebranded 'Working Families Tax Cut'

- OBBBA and New Year’s resolutions

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- MetLife Declares First Quarter 2026 Common Stock Dividend

- Using annuities as a legacy tool: The ROP feature

- Jackson Financial Inc. and TPG Inc. Announce Long-Term Strategic Partnership

- An Application for the Trademark “EMPOWER PERSONAL WEALTH” Has Been Filed by Great-West Life & Annuity Insurance Company: Great-West Life & Annuity Insurance Company

- Talcott Financial Group Launches Three New Fixed Annuity Products to Meet Growing Retail Demand for Secure Retirement Income

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

- Tea Party to learn about Medicare changes

- Richard French: Social Security cuts

- New Evidence on the Growing Generosity (and Instability) of Medicare Drug Coverage

- Why drug prices will keep rising through Trump’s second term

- Rising health costs could mean a shift in making premium payments

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News