The Power of Persuasion — with Lynne Franklin

Lynne Franklin’s experience as a social worker taught her everything she needed in order to survive in the business world. That started her on a path of answering the question: “How do you get others to do what you want?”

Franklin’s journey took her from positions such as a reporter for a weekly banking publication to jobs with public and investor relations agencies to starting her corporate communications and marketing practice — Lynne Franklin Wordsmith — in 1993.

A self-described “neuroscience nerd,” she studies how the brain works, how this affects the choices people make, and how to create communications that move their minds to action. A professional speaker and trainer on persuasive business communication strategies, Franklin works with entrepreneurs and business leaders.

Franklin is the author of Getting Others To Do What You Want. In this interview with Publisher Paul Feldman, she describes how we can do a better job of connecting with clients to get them to say “yes.”

Paul Feldman: I love the title of your book: Getting Others To Do What You Want. How do we get others to do what we want?

Lynne Franklin: Well, first, because I’m a neuroscience nerd, I study all the boring brain research. And then I try to figure out what this means in the real world to help us do a better job of connecting. If I had to boil it down, I’d say I fast track leaders to be seen, heard and promoted.

All of this is about figuring out ways to better connect with other people, to make sure that your message lands in a way they can see it, hear it and feel it. And then to help them make a good decision about whether what you propose is what they ought to do. So it’s not just my opinion. It’s based on science.

Feldman: Where do we start?

Franklin: We start with knowing who other people are. It’s one thing to want to know more about yourself and how you are in the world, but it’s a little hard to sit across the table from somebody and figure out who they are.

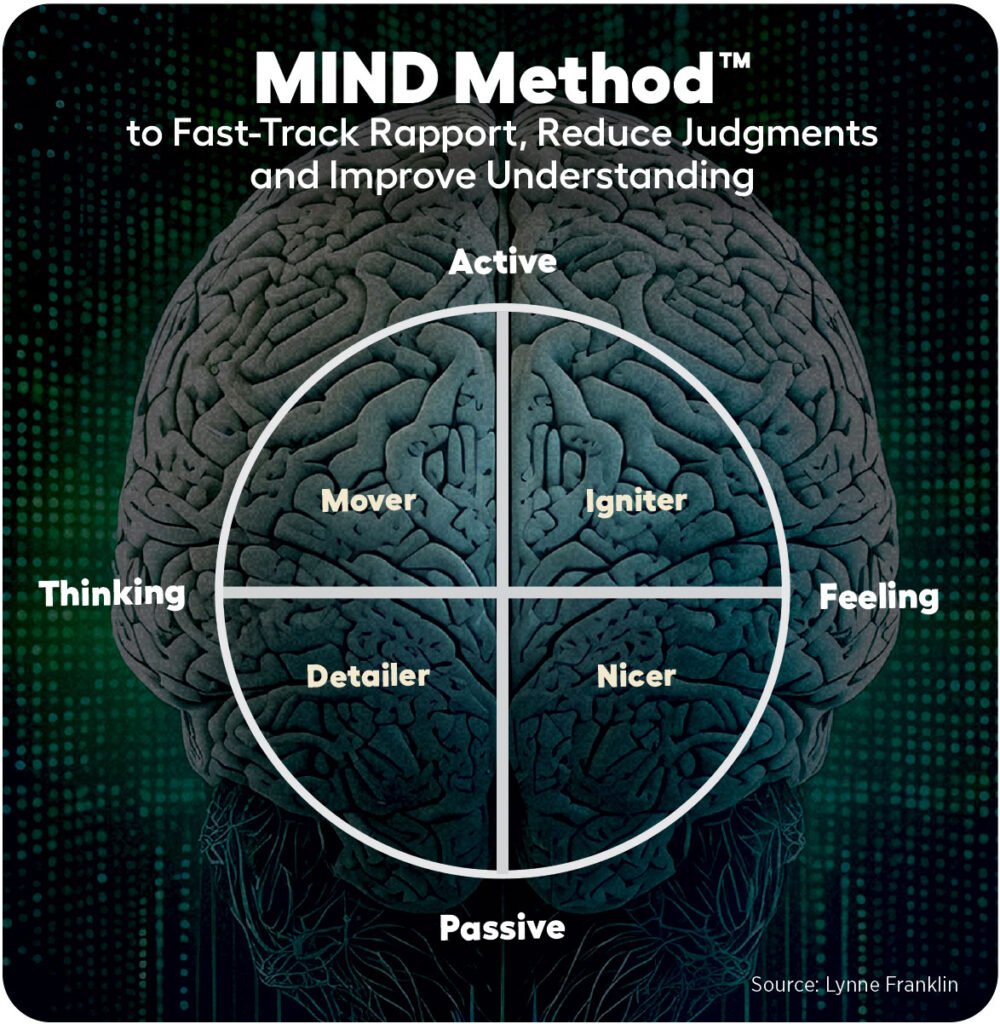

I have my own four-quadrant system. The acronym for it is MIND. In this instance, “M” stands for movers. These are the people who want to get stuff done, and want to be “large and in charge” and in control of the situation. What they’re mostly afraid of is not being in charge and not being in control.

“I” stands for people who are igniters. They want to ignite, change and lead change, and have people follow them and be inspired by them. What they’re afraid of is that people will not follow them and will not see the contribution they make.

Then we have “N,” which is for nicers. These are people who want everybody to be involved and play well together. What they are afraid of is being excluded.

And finally, we have “D” for detailers. These are the people who cannot get enough information. Detail is where they live. What they’re afraid of is making mistakes. They figure the more details they get, the less likely they are to make a mistake.

You can sit across the table or Zoom or anywhere, watch how people are and figure out which of these are their primary styles.

Feldman: Once you’ve figured out who they are, what can you do with that knowledge?

Franklin: You decide how you will present the information you have to share with them in a way that is most comfortable for them. So, for example, if we’re talking about the movers, these people want just enough information to be able to make a decision. If we’re talking about the detailers, the absolute opposite is true. They want as much detail as you can give them. If we’re talking about the igniters, these are the people who want to get information in a way that shows how they can inspire others and get others to follow them. And if we’re talking about nicers, they want to see how everybody can work together to get to where we want to go as a group.

It’s about having this basic understanding of how people operate. The truth is, we all have all four of these characteristics. But we have a primary style. By observing what people are saying and doing, you can figure out which of these characteristics is their primary style. Then you have a clue of how best to share the message that you want to deliver to them.

Feldman: That makes sense. Let’s say you’re with somebody who is a mover. How do you connect with a mover?

Franklin: What you want to do is present enough information to show them how they can make a good decision. Don’t give them a whole lot of information. Just give them enough, because you want them to know that the decision is theirs.

One thing you can watch for is whether they show any indications through their body language — whether they’re showing any nervous tics, whether they’re not making eye contact with you anymore, or whether they are checking their phones or doing something else. At that point, you know you’ve gone on too long.

When you see signs like that, stop and ask them, “Do you have any other questions?” Or you can ask them, “What can we do to move this forward on your behalf?” Movers are the people who are used to being leaders.

Feldman: If you recognize that your client is an igniter, how do you work with them?

Franklin: If you’re dealing with an igniter, you want to show your appreciation of them. You indicate that you’ve heard what they have to say, that you’ve been listening closely. You appreciate their viewpoint. And as a result of understanding what their viewpoint is, this is what you recommend for them to get to where they want to go.

Once again, you look for those nervous signs that someone is not paying attention to you. If you observe any of those signs, you know it’s time to move on.

Feldman: What about nicers? How do you work with them?

Franklin: Nicers will sit there and smile at you all day long! These people are afraid of conflict. They are not going to ask you questions about things because they don’t want to be perceived as being pushy or not being nice. So you need to show them how what you propose helps them meet their goals. And those goals are usually community based: What do they want for their family? What kind of legacy do they want to leave? Listen carefully to what they say they want to have in community, usually with their family. Then talk to them using “If I were you” statements. Because nicers often won’t ask questions. They are afraid of conflict. So you can say to them, “If I were you, I’d be curious about this,” and go in that direction to make sure you’re giving them enough information.

Feldman: That leaves us with detailers. How do you work with them?

Franklin: Once again, you cannot give them too much information. Be prepared to get lots of questions that drill down into the details.

You’ll also want to give them information that is printed, or you give them some kind of additional data they can access after the conversation is over. Because detailers are afraid of making a mistake, they use information to soothe themselves. They think, “The more information I have, the less likely I am to make a mistake.” Detailers will take a long time to make a decision versus a mover who will hear just enough information and then go ahead.

Feldman: One of the things you talk about is the Persuasion Cycle. Talk us through that.

Franklin: The Persuasion Cycle comes to us from Dr. Mark Goulston, who, among other things, does hostage negotiation and consulting for federal agencies. As Goulston was doing this kind of work, he started paying attention to the point when you know that people stop resisting you if they’re standing on a ledge and you’re talking them off the ledge. What’s that point? What’s the process of getting to that point? You need to take them from the point where they’re not going to jump off the ledge to where they step off safely.

He mapped out this cycle for us. I’ll look at the 10,000-foot view, and then I’ll talk a little bit more in detail about the different steps that are particularly applicable to us as people who are giving customers insurance and financial advice.

First, everyone starts at the top in resisting and our goal is to move people from resisting to listening to considering, from considering to willing to do, and then from willing to do to doing.

Neuroscience is why we start in resistance. Back in the days when we were in the jungle, our brains only had one job, which was to keep us alive. So, our brains were constantly standing on the horizon looking for physical and verbal risks and threats and trying to get us out of the way.

So, whenever you present a new idea to a current client or a prospect, part of their brain is asking: “Is this going to kill me? Am I going to get in trouble for doing this?” People automatically resist you. It’s like there’s an actuary living in their brain, and everything goes to the actuary first. How do we move people out of that? Here are the ways this applies to all four personality styles I described earlier.

The first thing you do is listen. There are two main types of listening. The first is listening to respond, which is hearing what is being said, processing that information, and then, while they’re speaking, you figure out what it is you’re going to say next. This is where we live most of the time, which serves us just fine. But when you’re trying to move somebody from resisting to listening, all you’ll get when you listen to respond is data. You’re not going to build a connection.

To move people along, we need to create a connection. So, you opt for the second type of listening, which is called “listening for understanding and empathy.” This means we’re not only paying attention to what it is that they’re saying, we’re also paying attention to their body language. Do they look nervous or frightened? We’re also paying attention to their tone of voice.

We’re paying attention to their emotions, so that we’re getting a picture of the whole person — not just what they’re saying. Concentrating on them takes energy. But it’s good energy because you’re picking up the entire picture of who this person is. Then, when it’s your time to speak, you can draw on so much more.

Most of us wander through our lives feeling chronically unseen and unheard, and when somebody gives us their entire attention and focus, we appreciate that. Then something else happens, and it’s called the rule of reciprocity. When we have given somebody all of our attention, sooner or later most people will notice this.

They really do want to hear what you have to say at that point, because you’ve listened so well to them. That’s how we move people from resisting to listening. We listen to them first.

Feldman: How do you move people from listening to considering?

Franklin: We start by asking good questions and paraphrasing what we’ve heard. Here’s the biggest mistake people make — especially those of us who are skilled in our areas in insurance and financial advising.

Listening to people, we kind of already know early on what it is that they need. We’re ready to jump into that. But we have not yet earned the right to do that because if we do that now, we will push people back into resisting.

This is why during the “listening” to “considering” phases, asking questions — paraphrasing what has been heard to make sure that we’re understanding correctly — deeper listening is important.

It’s when we have this kind of information, we can then start proposing ideas because the prospective clients are feeling that we’ve built up enough goodwill with them and we’ve shown them we’re paying attention. Now we have something to suggest to them.

That moves them into the considering phase, which is when we can actually provide information to them. So don’t rush to create a solution. What you’re trying to do in this front part of the cycle is to create connection. You do that by listening, asking good questions and paraphrasing.

When they’re considering, you’re trying to answer their questions. Their questions get more specific about what it is that you are able to do with them or the solutions you’re proposing, because that moves them into willing to do.

And frankly, once they’re in the “willing to do” space, that’s a snap.

Agents and advisors know their offerings and the needs of this person they’re speaking with. That’s the easy part. So, it’s this whole front end of the cycle where we’re trying to get buy-in, moving people from “resisting” to “listening” to “considering” — that’s the toughest part.

You may end up thinking, after you’ve gone through this, that the person is in “willing to do.” And you get excited about this. OK, so now, we can actually make a difference for this person. But at that point you may end up with them saying, “Well, you know, I have to think about this,” or “I’m going to have to talk to my wife or my spouse about this.”

Here’s the thing about persuasion. Most of us think it’s a binary thing, that it’s a yes or no. It’s actually a process, which is what this whole Persuasion Cycle thing is about.

When people say what appears to be a “no,” that doesn’t mean “no,” really. It means they’re confused.

Feldman: How do you take that final step, so that they’re finally willing to commit?

Franklin: There’s usually something missing. We must be able to turn to them — and everybody will have their own language — and ask, “Is there anything I could have said or done that would have made it possible for you to say yes to this?” And then shut up. Because when we ask a person a direct question like that, most of the time people will be able to come back to us and say, well, you didn’t talk to me about this, or I don’t understand this. Then you can say, “My bad. Let me tell you a little bit more about that.”

There’s a sales coach by the name of Brian Tracy who calls this The Doorknob Close. And he says, when you ask this kind of question, 50% of the time people you thought were going to say no to you will say yes to you, because what you’re dealing with is buyer’s remorse. People are suddenly afraid of something that they don’t know, and if you can walk them through that thing that they don’t know, they’re more willing to say yes to it.

You can see that when you’re moving somebody from “resisting” to “listening” to “considering” to “willing to do,” instead of requiring people to make a quantum leap to say yes or no, you’re moving them along in this process. That’s what makes this great. It’s bite-size pieces rather than quantum leaps.

Once you get somebody to “willing,” and you know your customers well, you can take them from saying “yes” to “glad to do it.”

Feldman: So, would you call that persuasion?

Franklin: Let me give you my definition of persuasion. And it’s not like anybody else’s. Persuasion is presenting your ideas in a way that people can see them, hear them and feel them — and then make a good decision about whether what you’re proposing is what they ought to do. And if it is, then to say “yes” faster. And if it’s not, then to say “no.”

But along the way, you have built such goodwill with them that should they ever need what you do, they’ll come back to you. Or if they run into somebody else who needs what you do, they’ll refer you.

So being persuasive is not about getting everybody to say yes to you, because everybody shouldn’t say yes to you. It is actually about helping people make good decisions. Which means you’re never a salesperson. You’re an advocate on behalf of your current or prospective customers.

It’s not the hard sell. I think most people confuse persuasion with being manipulative. No, it’s all about helping people make good decisions because you listen well to what they have to say, and you play it back to them, and you show them what you can do and help them get to where they want to go.

It’s not sales. It’s persuasion.

It gives them a chance to make a good decision.

How tech will revolutionize health care and life insurance

Would you rather purchase items retail or wholesale?

Advisor News

- Goldman Sachs survey identifies top threats to insurer investments

- Political turmoil outstrips inflation as Americans’ top financial worry

- What is the average 55-year-old prospect worth to an advisor?

- A recession could leave Americans humming 'Oh, Canada'

- Market volatility driven by fear, emotion

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

Health/Employee Benefits News

- Latest state Dem hospital cost reform skips Econ 101 | HUDSON

- Bill would provide firms refundable tax credit for health-plan premiums

- Most Ugandans Lack Medical Aid Coverage and Worry About Being Unable to Afford Care

- Landry budget grows Medicaid

- GUEST COMMENTARY: We need a better system to pay for health care

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News