Hiking the ‘tax max’ could solve the Social Security problem, expert says

It often seems that the solution to the Social Security funding problem is Washington, D.C.'s unicorn. In other words, it doesn't exist.

A panel of experts assembled by the American Academy of Actuaries disagreed Wednesday. The answers are actually quite numerous and obvious, the experts said. And Congress will eventually adopt one or, more likely, a combination of them.

"Fear not about Social Security going away. That's not going to happen," said Stephen Goss, chief actuary at the Social Security Administration. "The challenge is for Congress to come up with ways to either bring down the scheduled benefits, raise the tax revenue coming in, or some combination of the two, which they have always done in the entire history of this program."

The panel discussion highlighted day two of the AAA's 2024 Annual Meeting.

Unless Congress acts, Social Security’s primary trust fund will be depleted in 2033, according to a 2024 report by the trustees. When that happens, each beneficiary will see their benefit cut immediately by 21%.

Lawmakers have known for decades that Social Security’s finances are unsustainable. The program an estimated $23 trillion short over the next 75 years, a gap between projected inflows and benefit payments that continues to grow. Yet, the last major adjustment to the Social Security program came in 1983 when Congress addressed both short-term financing needs and long-term challenges.

Prior to that, lawmakers regularly updated the program’s tax rates, tax base, benefit amounts, and other policy parameters, the Bipartisan Policy Center noted earlier this year.

Tax base dwindling

There are common misconceptions about why the Social Security fund that supports retirees through monthly checks is running short of money. It is not because Americans are living longer, Goss said. The biggest reason is the shortage of taxable income, he explained.

Social Security is funded through a payroll tax of 6.2% paid by both employers and employees (for a combined 12.4%) up to a certain level, known as the taxable maximum. Self-employed workers pay the full 12.4% tax. The SSA adjusts this limit annually to keep pace with the average wage index. In 2024, earnings up to $168,600 are subject to the Social Security tax.

Between 1983 and 2000, earnings for the wealthiest Americans "grew a lot faster than earnings levels for lower earners," Goss noted. The top 6%, the ones with earnings above the taxable maximum, grew by 62% over that 17-year period, he said, while earnings by the lower 94% grew by 17%.

"That really is the primary reason why we're falling short now relative to what we were expecting back in 1983," Goss said.

Among the presidential candidates, Democrat Kamala Harris supports applying the Social Security tax to higher incomes. Republican Donald Trump has not endorsed specifics regarding Social Security, but pledged to not cut benefits.

Raising the 'tax max'

Joel Eskovitz is a senior director of Social Security and savings at the AARP Public Policy Institute. Raising the revenue is the most immediate need, he explained. Changes to benefits, like raising the retirement age, will take decades to kick in and change the actuarial assumptions.

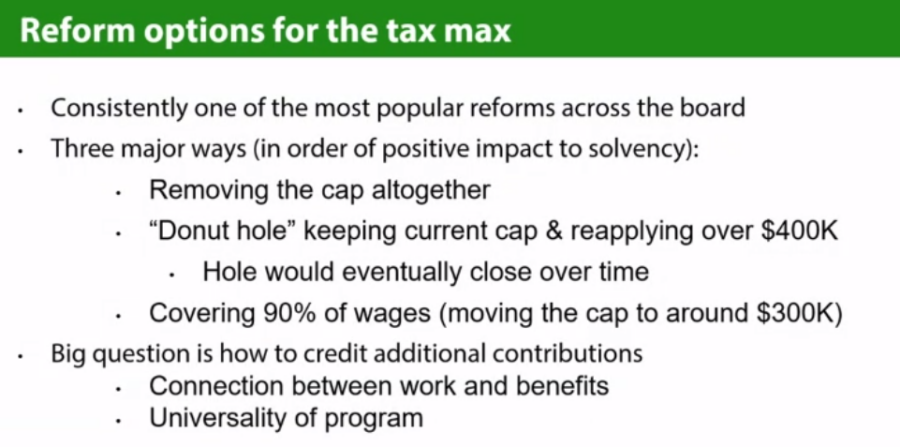

Raising the earnings minimum for the Social Security tax is usually the most popular solution to the revenue problem, Eskovitz said.

"Six percent of people earn above the cap, and so obviously people always love a solution where they don't have to pay more," he said.

Beyond that, "there's an inherent fairness issue there," Eskovitz said. Many people are shocked to find out that while they pay into the Social Security system from every paycheck, not everyone does.

"There are people who've stopped paying in, if you're a millionaire, in the first quarter," he said. "There's always those stories about people who stopped paying in after the first week of the year."

Emerson Sprick represented the Bipartisan Policy Center on the panel. The BPC floated a Social Security proposal eight years ago, noted Sprick, an economist and associate director of economic policy at the nonprofit organization.

The BPC's "balanced package of benefit adjustments and tax increases" would have made Social Security fiscally sustainable and boosted income in retirement for the lowest-earning workers, the organization has said.

Since Congress did not act then, a different answer is needed today.

"The important thing to think about in thinking about Social Security reform is not what any individual provision does, but rather what collection of reform provisions put together in a politically realistic way, which is the biggest challenge, does both for the long run solvency of the program and for the distribution of income," Sprick told the AAA audience.

© Entire contents copyright 2024 by InsuranceNewsNet.com Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reprinted without the expressed written consent from InsuranceNewsNet.com.

InsuranceNewsNet Senior Editor John Hilton has covered business and other beats in more than 20 years of daily journalism. John may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @INNJohnH.

MassMutual to shut down insurtech subsidiary as Haven brand fades

Tariff hikes could cause GDP to fall, economist says

Advisor News

- Main Street families need trusted financial guidance to navigate the new Trump Accounts

- Are the holidays a good time to have a long-term care conversation?

- Gen X unsure whether they can catch up with retirement saving

- Bill that could expand access to annuities headed to the House

- Private equity, crypto and the risks retirees can’t ignore

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- New York Life continues to close in on Athene; annuity sales up 50%

- Hildene Capital Management Announces Purchase Agreement to Acquire Annuity Provider SILAC

- Removing barriers to annuity adoption in 2026

- An Application for the Trademark “EMPOWER INVESTMENTS” Has Been Filed by Great-West Life & Annuity Insurance Company: Great-West Life & Annuity Insurance Company

- Bill that could expand access to annuities headed to the House

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

Life Insurance News

- Judge tosses Penn Mutual whole life lawsuit; plaintiffs to refile

- On the Move: Dec. 4, 2025

- Judge approves PHL Variable plan; could reduce benefits by up to $4.1B

- Seritage Growth Properties Makes $20 Million Loan Prepayment

- AM Best Revises Outlooks to Negative for Kansas City Life Insurance Company; Downgrades Credit Ratings of Grange Life Insurance Company; Revises Issuer Credit Rating Outlook to Negative for Old American Insurance Company

More Life Insurance News