When kittens go wild – how climate change is increasing loss

Who doesn’t love kittens? Well, the property/casualty insurance industry for one.

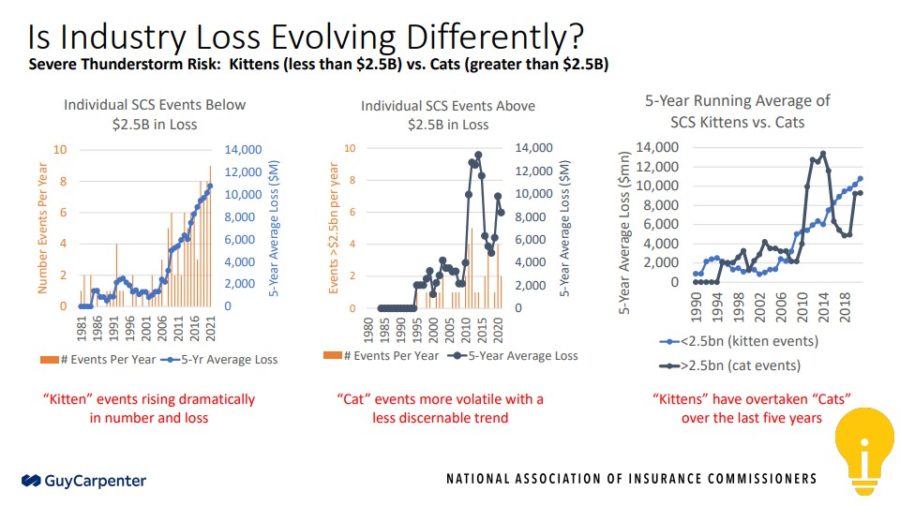

No, we’re not talking about those balls of fluffy fur with eyes. But in the parlance of Josh Darr, head of North American Peril Advisory, Guy Carpenter, kittens are smaller industry loss events, between $1 billion and $2.5 billion as opposed to catastrophic events, or cats, of more than $2.5 billion. Why would smaller industry losses be a problem? Because there are huge litters of little losses lately.

Darr explained in a session at the National Association of Insurance Commissioners’ 2022 Insurance Summit that thunderstorms and other smaller events have been costing the industry more money over the past several years, even with the historic catastrophic events grabbing the headlines in the past few decades.

As the number of kittens grows, we are seeing fewer cats – fewer wildfires and hurricanes making landfall – but those cats are huge.

In the chart above, the kittens are in the left graph, showing a steep increase over the past 15 years. The graph in the middle shows the cats, where single huge events can spike a year. Put together on the right, we see that kittens are costing more than cats, even with enormous losses with tornadoes, hurricanes and wildfires.

One of the immediate effects is a greater burden on insurers because the smaller events are not backed by reinsurers.

Weather events are growing more severe, but that is not the whole story. Exposure has grown with population sprawl. Decades ago, if a thunderstorm felled a tree in the woods, would an insurance agent hear about it? Not unless it fell onto a house or car, which is more likely today with suburban and warehouse sprawl.

But it’s not just more people in harm’s way, weather events themselves are packing a harder punch, mainly because of rising temperature.

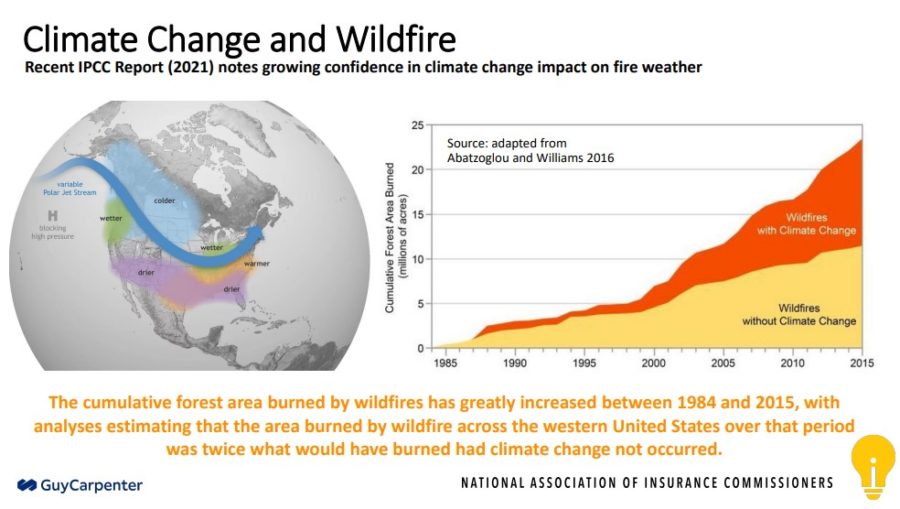

“The atmosphere gets hungrier for moisture the warmer it gets,” Darr said. Hotter air retains more moisture to drop in storms. That moisture is not where it needs to be out west, where lakes, rivers and forests are drying up, causing ripe conditions for wildfire.

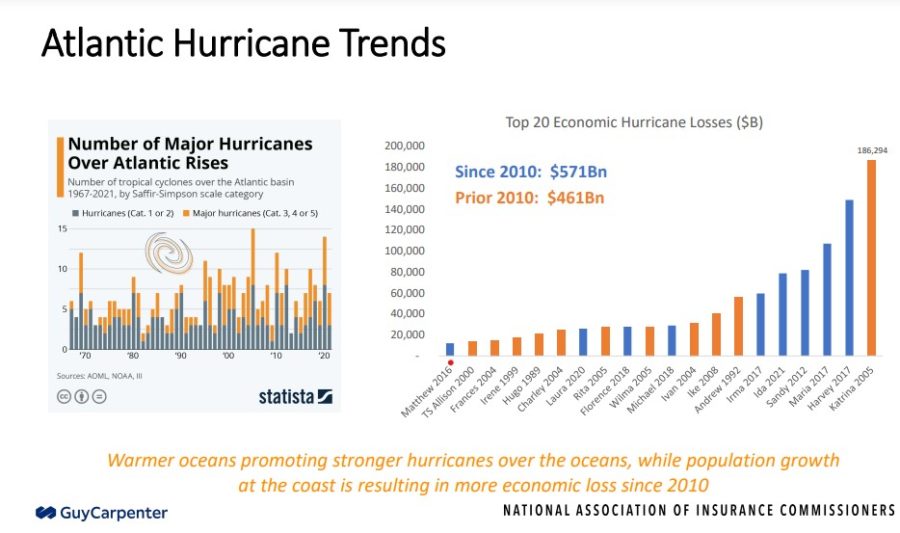

Here’s the kicker – there have been fewer hurricanes making landfall and fewer wildfires in the past several years, but they were doozies when they happen. Although the number of Atlantic hurricanes have increased, many have avoided landfall.

Hurricane Ida was a wowza

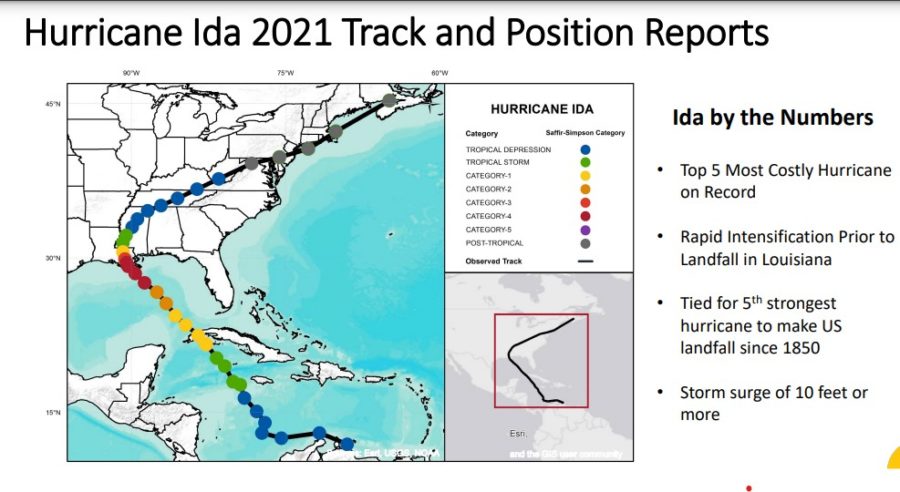

Hurricanes have been breathtaking in their destruction, but the focus is all on the landfall, with TV reporters leaning into the wind as the latest storm approaches shore. But that damage, while significant, is only the start of the story. Take Hurricane Ida for example.

Ida slammed into Louisiana in 2021 after intensifying from a category 1 to nearly a 5 in 24 hours, making it one of the fifth strongest storms to make landfall (there are a few contenders for the fifth strongest). The warmer water in the Gulf of Mexico contributed to that rapid intensifying, Darr said.

Storm surges were high and Louisiana’s land has been sinking, so that was an unfortunate combination.

“Ultimately, it was the top five most costly hurricane on record,” Darr said. “But it didn't all happen in Louisiana.”

Ida took a slow walk up the country, making a right toward the East Coast, gaining more moisture from a cold front along the way. New York City was stunned by the deluge, where people drowned in basement apartments and rivers ran down subway stairs. It was by far the top one-hour rainfall amount ever recorded in Central Park, hitting three inches in an hour. That was on top of the second highest just days earlier, when Hurricane Henri dropped two inches in an hour.

The damage spread from New York City down to Philadelphia, making Ida the fifth costliest storms of all time at $29.2 billion, but $7 billion of that loss was due to inland flooding in the northeast and mid-Atlantic.

Although the historic intensity of storms over the past decade is undeniable, there have been fewer storms making landfall in the past 10 years than in the average over the previous 30 years, Darr said.

The losses are greater now because of everybody who wants a piece of paradise next to the water, increasing not only they number of risk exposures but the property value of those losses.

When fires go wild

Wildfire is another dichotomy. Although there are fewer of them, they tend to be wide-ranging because of long-term drought conditions. Combine that with greater sprawl into harm’s way and we have the crisis out west.

Only three of the top 20 largest wildfires in California occurred before 2000. Three of the top fires occurred in just the past two years.

More than 50% of the largest wildfires have occurred in the past few years. To mix metaphors, the increase in dryness, heat and drought creates the perfect storm for wildfire risk. Add to that more ignition risk with more people living in those areas.

Warmer temperatures and erratic climate are key drivers to not just cats – catastrophic losses – but kittens as well. One global solution is to reduce carbon emissions from energy production by bringing on more green sources. The problem is getting that energy to the user.

“Our aging infrastructure certainly is impeding our ability at times to be a resilient society and effectively mitigate,” Darr said. “The power grid itself is increasingly unreliable due to transmission distribution lines getting older.”

As an example of the failing system, the enormous Dixie Fire that burned a million acres in Northern California earlier this year was caused by faulty PG&E transmission lines.

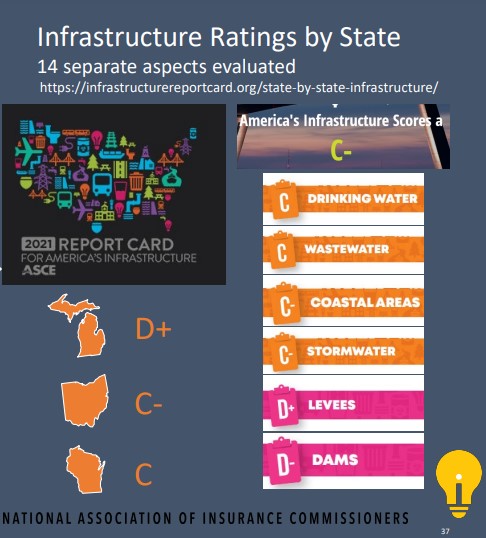

While dirty energy sources, such as coal, are being replaced by geothermal, wind and solar sources, among others, the power grid might not be able to handle it, said Darr, who showed an American Society of Civil Engineers infrastructure report card, although he said it might be harsher than he would be.

The ASCE gave the United States a C-minus overall, but dams and levees were the lowest on the list.

“If you're writing flooding in a state where your dams are D-minus or an F,” Darr said, “that might be something you want to consider as part of your overall risk tolerances in the way you think about flood, let alone what's happening with a future climate.”

Steven A. Morelli is a contributing editor for InsuranceNewsNet. He has more than 25 years of experience as a reporter and editor for newspapers and magazines. He was also vice president of communications for an insurance agents’ association. Steve can be reached at [email protected].

© Entire contents copyright 2022 by InsuranceNewsNet. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reprinted without the expressed written consent from InsuranceNewsNet.

Steven A. Morelli is a contributing editor for InsuranceNewsNet. He has more than 25 years of experience as a reporter and editor for newspapers and magazines. He was also vice president of communications for an insurance agents’ association. Steve can be reached at [email protected].

Nationwide, Ohio State team up for AgTech Innovation Hub

RMD strategies: Funding the ‘third trimester’ of life

Advisor News

- Todd Buchanan named president of AmeriLife Wealth

- CFP Board reports record growth in professionals and exam candidates

- GRASSLEY: WORKING FAMILIES TAX CUTS LAW SUPPORTS IOWA'S FAMILIES, FARMERS AND MORE

- Retirement Reimagined: This generation says it’s no time to slow down

- The Conversation Gap: Clients tuning out on advisor health care discussions

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- Great-West Life & Annuity Insurance Company Trademark Application for “EMPOWER READY SELECT” Filed: Great-West Life & Annuity Insurance Company

- Retirees drive demand for pension-like income amid $4T savings gap

- Reframing lifetime income as an essential part of retirement planning

- Integrity adds further scale with blockbuster acquisition of AIMCOR

- MetLife Declares First Quarter 2026 Common Stock Dividend

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

- New Findings from University of Colorado in Managed Care and Specialty Pharmacy Provides New Insights (Primary Care Physicians Prescribe Fewer Expensive Combination Medications Than Dermatologists for Acne: a Retrospective Review): Drugs and Therapies – Managed Care and Specialty Pharmacy

- Reports Summarize Health and Medicine Research from UMass Chan Medical School (Supporting Primary Care for Medically and Socially Complex Patients in Medicaid Managed Care): Health and Medicine

- New Findings Reported from George Washington University Describe Advances in Managed Care (Few clinicians provide a wide range of contraceptive methods to Medicaid beneficiaries): Managed Care

- Reports Outline Pediatrics Study Findings from University of Maryland (Reimagining Self-determination In Research, Education, and Disability Services and Supports): Pediatrics

- Rep. David Valadao voted to keep health insurance credits but cut Medicaid. Why?

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News