Hall of Fame, Fall of Shame: Marshall Faulk Loves Planning With Insurance

Professional athletes encounter a lot of the financial risks and rewards that come with big-money careers. Meet pro athletes who became financial success stories in their post-playing days — as well as a few who didn’t.

Why Athletes Are Going Broke

Pro athletes face many tough choices upon signing that first big contract. Some find out quickly that a million dollars doesn’t go very far.

It is a regular feature of being a rookie in the National Football League that at some point during training camp, the veterans will gather at an upscale establishment to eat a mountain of food — with the rookie getting the bill.

In one famous example, Dallas Cowboys rookie wide receiver Dez Bryant was stuck with a $54,000 bill for a team dinner in 2010.

It might fall short of hazing. It might be great for team bonding. And for some, it might be the start of a professional career filled with big paychecks and bigger bills.

“There’s absolutely this peer pressure part of it,” said Matt J. Goren, assistant professor of financial planning at The American College of Financial Services. “I have my family. I have my friends. I’ve got teammates. And everybody is telling me to spend a ton of money.

“If you have no frame of reference, how much is $50,000 for one dinner? That seems like a ton of money, but when all these other guys are doing it, maybe it’s not that much money. Maybe I can afford it.”

Professional team sports are filled with tales of reckless spending and absent financial planning.

Lack of role models is a big part of the problem, Goren said, along with many athletes coming from low-income, low-financial literacy backgrounds.

“You get these circumstances where these guys, even as high schoolers, such as Lebron James, are signing multimillion-dollar contracts,” he explained. “And you have no frame of reference for what you’re getting yourself into.”

Things are slowly changing, and progress is being made. Most pro sports leagues include financial literacy as part of rookie orientation. Likewise, major colleges that turn out a lot of athletes are offering financial literacy programs.

Meanwhile, athletes continue to make headlines for financial choices good and bad. Here are three such stories from each category.

Hall of Fame

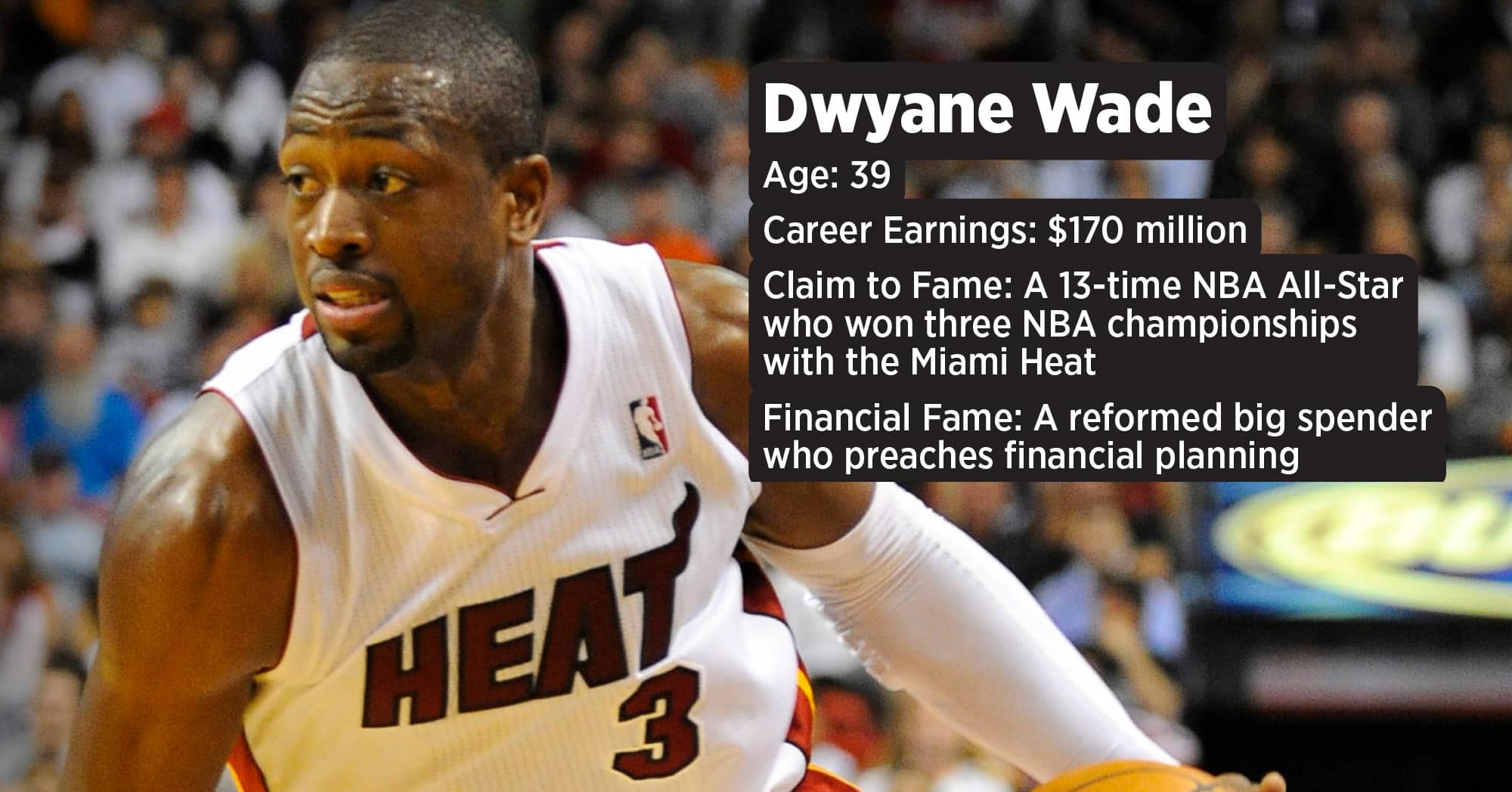

Dwyane Wade

Born in Chicago in the winter of 1982, NBA superstar Dwyane Wade did not have a happy childhood, and his early education was largely provided on the streets.

Dwyane Wade Sr. and Jolinda Wade separated when Wade was four months old and later divorced.

Wade lived on the South Side of Chicago with his mother and two sisters until he was 8. At that point, he moved to live with his father.

During interviews, Wade has described the difficulties of this period. His mother was on drugs, and he was surrounded by gang influences. The police raided their home when he was 6. His mother did time in prison, but today she is the pastor of a church in Chicago.

Two things saved Dwyane Jr.: his father and basketball. In his book, A Father First: How My Life Became Bigger Than Basketball, Wade credits his dad with stepping up to be a committed parent.

Once he sprouted to 6 feet, 4 inches, Wade’s basketball skills blossomed at Marquette University and during a long NBA career with the Miami Heat. But his early professional spending habits were not good. Wade has said his first big paycheck went to an electric blue Cadillac Escalade decked out with 26-inch rims and spinners.

Wade continued to collect cars until he received what he called the best money advice of his career, he told Men’s Health in a 2020 interview. A financial advisor told Wade to get rid of the flashy vehicles, including a Maybach he never drove, but cost him $6,000 per month.

Wade listened and cut his fleet to “a modest Audi Q8,” he told Men’s Health. Although he made and wasted a lot of money, Wade said he learned his lessons along the way. It helped that he had strong earnings, topping out with a six-year, $107 million contract signed in 2010.

Today, Wade meets quarterly with a trusted financial advisor to map out his money goals. “A failure to plan is a plan to fail,” he has said.

Brent Celek

Young athletes are a prime target for financial schemes, and Brent Celek fell victim. In his case, a Ponzi scheme cost him money but gained him a lifelong education.

Celek, who played 11 years for the Philadelphia Eagles, would turn the experience into a positive, including a post-playing career as an executive with Patricof Co., a Manhattan financial investment firm. Celek leads the firm’s real estate vertical, counting a roster of former professional athletes such as Dwyane Wade and Ryan Tannehill as investors.

According to a March ESPN report, Celek sought out advice from a fellow player and connected with a money guy who seemed legitimate at first. The experience was costly for many players, with Celek losing $50,000.

“I think you learn really quickly, OK, I need to figure out how to do this the right way,” Celek told ESPN.

While not a star on the field, Celek achieved the pinnacle of professional football in February 2018 when the Eagles won their first Super Bowl. The tight end retired a few weeks later.

Being able to spend his entire career in one city afforded Celek the opportunity to establish business connections and develop opportunities off the field. Those business ventures include his own brokerage, mortgage and title company.

A move to investing and real estate seemed like a perfect fit for the Ohio native. Celek’s grandfather built custom million-dollar homes, and his parents are entrepreneurs.

“This is a great way for me to give back to some of my teammates — guys I played with and against — and just help these athletes preserve their wealth,” Celek said in an NFL Alumni story. “Helping these guys preserve the NFL money they earned does mean a lot to me.”

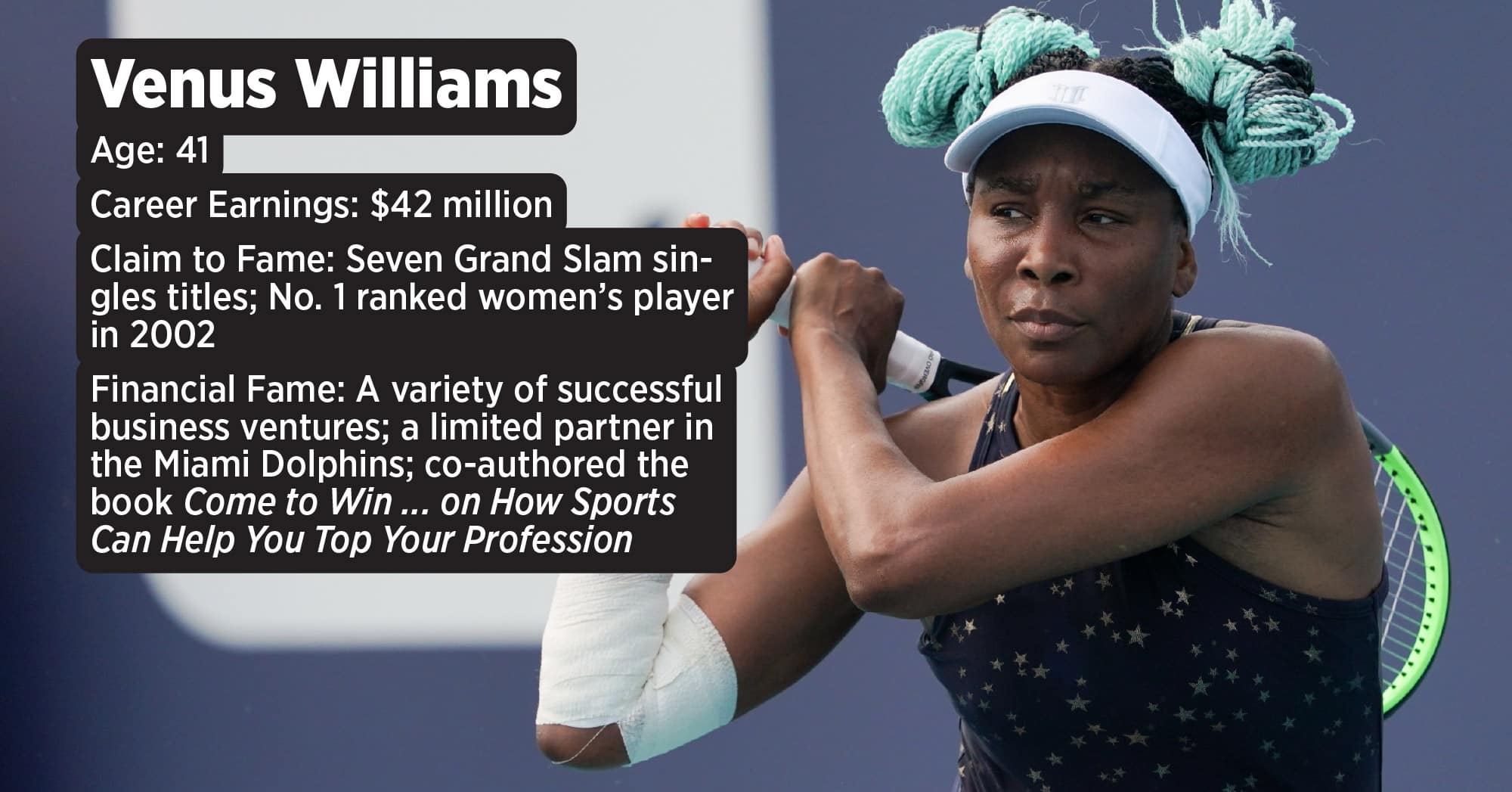

Venus Williams

The Williams sisters have proven as shrewd and tenacious in the business world as they are on the tennis court. And Venus has led the way.

The older sister was the first to make her mark on the court, turning pro at age 14 in 1994. Nearly 1,300 matches and 26 years later, the five-time Wimbledon champion continues to grind away.

Off the court, Venus parlayed her enormous winnings into a business empire. She is chief executive officer of her interior design firm, V Starr Interiors, located in Jupiter, Fla., a company that designs residences and offices in the Palm Beach, Fla., area.

Venus also has her own fashion line, EleVen. Together with sister Serena, she owns a piece of the Miami Dolphins football team. Like many young athletes, Venus is investing in creative and socially conscious businesses.

She backed a robo-investing application called ElleVest in 2017, a company with a mission centered on serving female investors. The Williams sisters are also invested in the UFC, the MMA league that has a $1.5 billion commitment from Disney and is still growing, financially and culturally.

Running her businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic proved to be “scary at times,” Venus acknowledged in a blog post.

“The effort would have been impossible without my amazing team,” she wrote. “They make me great, they make me better, they refine me. It wasn’t easy, there wasn’t a lot of sleep and it was scary at times, but thankfully it was mostly exciting.”

Fall of Shame

Evander Holyfield

First, the good news: Former heavyweight champ Evander Holyfield reportedly earns a decent income, as much as $100,000 a month, from personal appearances and other promotional activities.

The bad news is that the rest of his earnings — by some estimates, as much as $500 million — is gone.

It takes a lot of work to spend that much money, and Holyfield lost his fortune via four bad habits: gambling, bad investments, poor family planning and old-fashioned big spending.

He bought a mansion with 109 rooms, with a 135-seat home theater, a bowling alley and a dining room that can seat more than 100 people. The home cost Holyfield $1 million per year, according to the Daily Mail, in just taxes and upkeep. Holyfield sold the mansion to a bank during a public auction for more than $7 million, but that reportedly didn’t cover what he owed on it.

The boxer was a notorious gambler — and loser — in casinos from Las Vegas to Atlantic City.

But child support obligations to his 11 children by five different mothers are really where Holyfield’s debt ballooned. When he went broke in 2012, Holyfield reportedly owed about $500,000 in child support. According to court documents, his then-18-year-old daughter sued him for $300,000.

Holyfield’s business savvy was just as bad. He lost money on bad real estate deal and a failed restaurant chain, and he bet on a record label, Real Deal Records, that ate up cash.

Holyfield claims he has learned his lesson and has a handle on whatever income he earns today. However, the aging fighter seems to be still chasing a big payday and has teased a potential rematch with Mike Tyson in recent months.

“I think it will be a lot of money and a lot of millions,” he said on a podcast. “I think a hundred million. The fight would be big because so many people want the fight.”

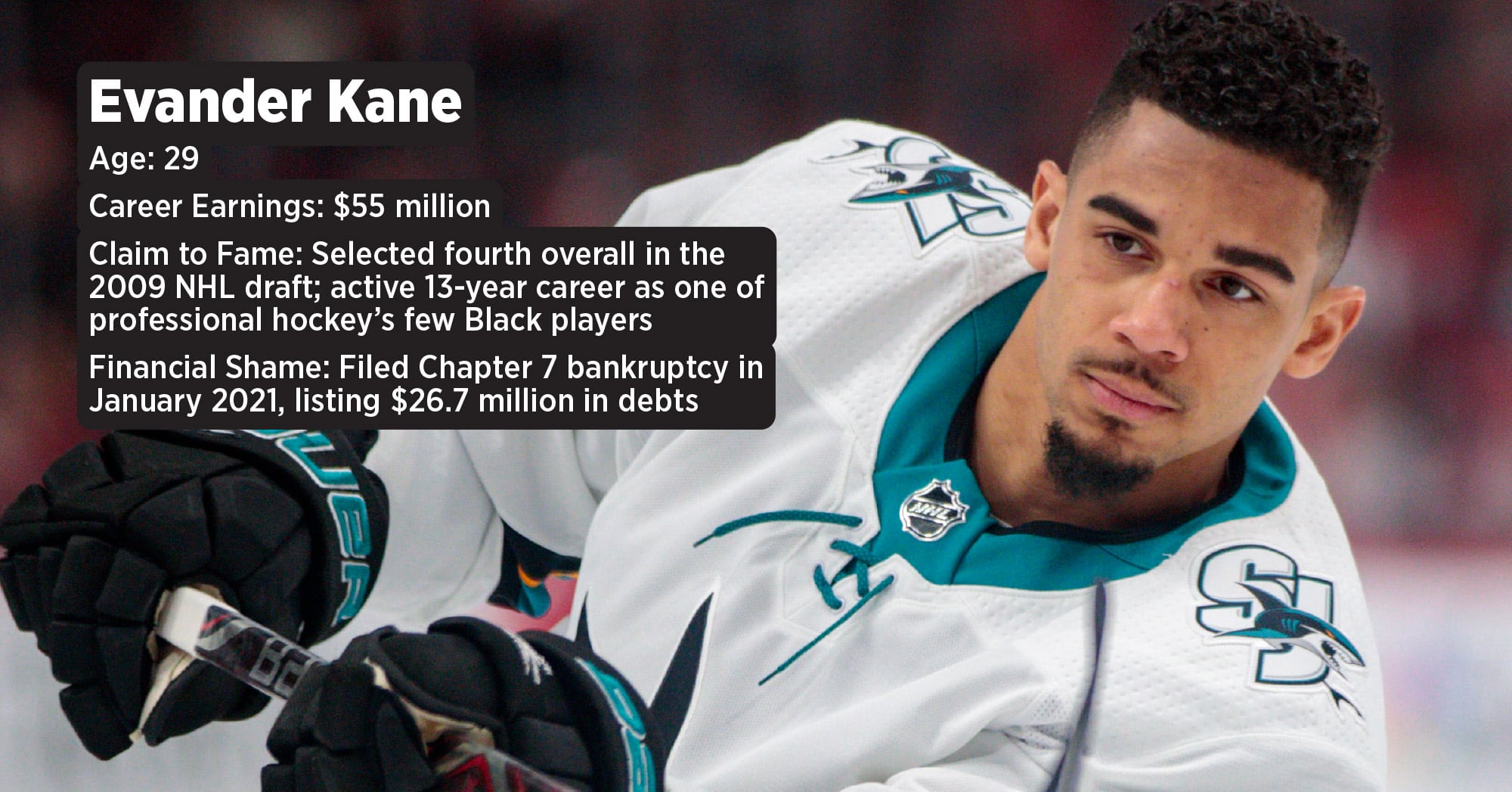

Evander Kane

Evander Kane was named after boxing legend Evander Holyfield, and the young Canadian NHL player would go on to mimic Holyfield’s life with years of unfortunate financial decisions.

In January, Kane finally stopped outrunning his debts and declared Chapter 7 bankruptcy. Despite being in his 12th season as a highly paid professional hockey player, Kane listed $27 million in debts.

On the downside of his career, the clock is ticking on his ability to earn his way out of that debt load. During recent interviews, Kane said declaring bankruptcy brought some relief.

“Yes, it’s been stressful to deal with a lot of the bankruptcy,” Kane told The Athletic. “It’s definitely been stressful. But it was a relief because I didn’t have to try and hide it anymore.”

A left winger, Kane is one of the few Black players in pro hockey. He was drafted fourth overall in the 2009 draft and doesn’t turn 30 until Aug. 2. He was well into a successful NHL career before his money problems surfaced.

On Nov. 4, 2019, Kane was sued by The Cosmopolitan casino in Las Vegas after he allegedly walked out on a half-million-dollar gambling debt. The suit alleged that Kane had received $500,000 in gambling markers from the casino the previous April and left the casino without making arrangements to settle the debt.

The bankruptcy filing included $10.2 million in assets for Kane, who is in the third season of a seven-year, $49 million contract extension signed with the San Jose Sharks in 2018.

Mark Brunell

Like many investors, Brunell focused on real estate as a seemingly safe place to bet his money. It turned out not to be safe at all.

A longtime NFL quarterback during the 1990s and 2000s, Brunell suffered his biggest losses on investments with friends.

He partnered with a pair of former teammates in a company called Champion LLC in order to get into the real estate game. Unfortunately, their timing was terrible. When the housing market crashed in 2008-09, Brunell lost all $11 million that he put into the deal and defaulted on a number of loans, the Daily Mail reported.

One of Brunell’s partners in the business, former teammate Joel Smeenge, declared bankruptcy.

Brunell was heavily invested in Whataburger, the popular fast-food burger chain. He invested $9 million and took ownership interest in 11 franchises, but ended up losing it all.

In 2010, Brunell and his wife, Stacy, filed their own bankruptcy petition. It listed $24.7 million in liabilities, with Brunell’s only income $5,000 monthly as president of Mark Brunell Enterprises, which operates football camps. Stacy Brunell also claimed a $5,000 income.

“The timing of the group’s real estate acquisitions at the height of the real estate market, in hindsight, clearly was not good, particularly given the subsequent collapse of the economy,” Brunell said in a statement following the bankruptcy filing.

Generally acknowledged as one of the good guys in pro football, Brunell played in the NFL for 19 years and made three Pro Bowls. He consistently gave his Southpoint Community Church a 10% tithe, which added up to significant contributions.

Brunell retired from the game the year he filed for bankruptcy. He reportedly went to work as a $60,000-a-year medical sales representative. He later coached high school football in Jacksonville, Fla., for seven years and was hired this year as the quarterbacks coach for the Detroit Lions.

The Marshall Plan

Hall of Fame running back Marshall Faulk is heading up a successful World Financial Group satellite agency in San Diego, part of his growing financial empire.

As a professional football player, Hall of Famer Marshall Faulk provided security for quarterback Kurt Warner.

Whenever the defense harassed Warner and the pocket collapsed, he would look to dump the football off to his St. Louis Rams teammate. Faulk caught 80 or more passes for five straight seasons and remains second in all-time career catches by a running back, with 767.

Now in his second career, Faulk provides financial security these days. Faulk has a long association with World Financial Group in San Diego and runs his own agency, offering a full array of financial and insurance products.

And Faulk is not just attaching his name to the door either. He quickly warms to the topic of financial literacy and the need to have the right kind of insurance, as well as the correct amount of coverage.

“It provided me the opportunity to get into the business, learn the business, and I realized how many people didn’t have insurance or didn’t have the proper insurance,” Faulk said. “I just wanted to change the way things were being done and reach out into the community that I grew up in.

“And be a little different than the regular insurance guy and provide some financial literacy with their insurance and then explain to them how their money is working for them.”

By the time Faulk, 48, retired from football following the 2005 season, he was accustomed to success. He was NFL Rookie of the Year in 1994, won a Super Bowl ring in 1999 and was the Associated Press Most Valuable Player in 2000. He was inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame in 2011.

By then, Faulk was on his way to achieving similar success as a businessman with a diverse portfolio.

Faulk expanded his holdings to include a Popeye’s Louisiana Kitchen franchise; part of Alliance Management Group, a full-service sports agency; part of San Diego-based Dirty Birds Bar and Grill restaurants; MAD Energy, a sustainable energy company he founded; and Midwest Elevators.

Then Faulk had a life insurance policy lapse, and he had questions.

“I was trying to get it reinstated, and I lost the cash value in it because it lapsed,” he recalled. “I started asking questions, and there weren’t a lot of people available to answer the questions.

Then I started to seek out and get the information on why this happens and found out that it happens a lot. So I really started to dive into the financial industry to try to get a better understanding of it.”

Through his sports agency, Faulk frequently reaches out to young players to preach financial literacy and advises them on opportunities to protect and grow their money off the field. Yet he understands why players continue to suffer financial woes.

Faulk favors more education on things such as how credit works and what compound interest is, to teach and motivate young people to better manage financial issues.

“If you don’t understand the inner workings of money, then you have to hire people and depend on them,” he said. “If you don’t come from a family that can help you with that, you’re most likely going to be in a position where you’re trusting someone who wouldn’t trust you with their money — but you’re going to trust them with yours.”

Going For The Green

A decade-long stint as a professional golfer gave Lee Williams great training to move into wealth management planning.

Long before he became a financial advisor, Lee Williams lived a life filled with money tests.

That life as a professional golfer forced Williams and his wife to adopt austerity measures, as his earnings were completely unpredictable. Golfers compete on a merit basis — just making the field at a professional tournament does not guarantee a paycheck.

The player must make the “cut,” which is usually established after the first two days of play. Even then, the paycheck fluctuates wildly with every made — or missed — putt.

Williams’ weekly tournament compensation ranged from a lot of zero paydays to $112,500.

“For most people, it’s more stressful. The typical golf career is year to year,” Williams said. “In terms of finances, you really have to plan further ahead. You’ve got to be more conservative in terms of what you do with your money. If you think in terms of locking up money, you probably sit on more cash than what would typically be recommended.”

A pro golfer’s experience is unique in sports, where most athletes are high net worth clients before they even play a game. The minimum salary in the National Basketball Association is $925,000. In the National Football League, it is $660,000.

While there is huge money in pro golf as well, it is usually earned after at least a few years struggling to compete. That does not mean pro golf lacks examples of the big financial failures found in other sports. Golfer John Daly lost an estimated $50 million to gambling.

For Williams, the experience of life as a pro athlete provided great training for the financial planning he does for his roster of high-net-worth clients today.

“We make sure that their assets are protected if something were to happen to them,” Williams said, “and their wishes are carried out, regardless of whether they’re here or not. I’m not a family office, but I’m set up similar to a family office, to where I can bring multiple components of finances under one roof, which is hard.”

A Decade On Tour

Williams, 39, bounced between the then-Nationwide Tour and the PGA Tour from 2005 to 2014. His lone win came in the 2012 Mexico Open, a Nationwide Tour event. Now known as the Korn Ferry Tour, the mini tour serves as a minor league of sorts for pro golfers.

In total, Williams made about $559,000 in prize money from both tours. His playing career came to a premature end in 2014, when nagging back injuries forced Williams to the clubhouse for good.

When Williams wasn’t golfing, or when he wanted a break, he escaped by reading about finance. The parallels between the sport and high finance might not be obvious, but Williams recognizes them.

“It’s a lot about strategy and thinking things through in depth and being very detail oriented,” Williams said. “All of that aligns with golf. When you play at a high level, it’s all about the details. It’s all about dissecting the golf course each and every week, and strategizing and figuring out what’s the most efficient way to get around this golf course.”

A two-time Academic All-American at Auburn, Williams graduated with a degree in economics. When his back problems flared up, Williams was in his early 30s with a family to support.

A transition to a financial services career was an easy choice. Today, Williams is a certified wealth management professional with Nowlin and Associates in Alexander City, Ala.

Williams partners with an estate planner and an accountant in order to provide the full range of planning services. It’s another approach that mimics his golf career.

As an amateur, Williams competed for the Walker Cup in a team competition between the United States and Great Britain and Ireland. Williams played on two teams alongside current PGA Tour players Bill Haas, Ryan Moore, J.B. Holmes and Bryan Harman.

‘Far Bigger Than You’

Williams described his client-first mindset in an interview with The American College of Financial Services earlier this year.

“Golf is an individual sport, except in these team events, where it’s about something far bigger than you,” he noted. “In financial services, it’s the same way. It’s not about you. It’s about your clients, their family, their business, their legacy. It’s an immense and humbling responsibility.”

Looking ahead, Williams hopes to break into his former arena. He has no pro golfers on his client roster and is working to establish himself with agents so he can get those referrals. Having lived the life, Williams is uniquely positioned to provide financial advice and management.

Regardless of who the client is, Williams sees his role as that of an educator.

“What I try to do is give people a high-level education,” he explained. “I’m not getting down into the weeds, but trying to give them a very broad overview of what we’re doing and why we’re doing it. I try to give them the information that I would want to have if I were on the other side of the table.”

InsuranceNewsNet Senior Editor John Hilton has covered business and other beats in more than 20 years of daily journalism. John may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @INNJohnH.

Green-Thumb Index Strategies For All Seasons

Americans Putting COVID-19 Financial Panic In The Past, Allianz Finds

Advisor News

- Study finds more households move investable assets across firms

- Could workplace benefits help solve America’s long-term care gap?

- The best way to use a tax refund? Create a holistic plan

- CFP Board appoints K. Dane Snowden as CEO

- TIAA unveils ‘policy roadmap’ to boost retirement readiness

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- $80k surrender charge at stake as Navy vet, Ameritas do battle in court

- Sammons Institutional Group® Launches Summit LadderedSM

- Protective Expands Life & Annuity Distribution with Alfa Insurance

- Annuities: A key tool in battling inflation

- Pinnacle Financial Services Launches New Agent Website, Elevating the Digital Experience for Independent Agents Nationwide

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

- Idaho is among the most expensive states to give birth in. Here are the rankings

- Some farmers take hard hit on health insurance costs

Farmers now owe a lot more for health insurance (copy)

- Providers fear illness uptick

- JAN. 30, 2026: NATIONAL ADVOCACY UPDATE

- Advocates for elderly target utility, insurance costs

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News

- AM Best Affirms Credit Ratings of Etiqa General Insurance Berhad

- Life insurance application activity hits record growth in 2025, MIB reports

- AM Best Revises Outlooks to Positive for Well Link Life Insurance Company Limited

- Investors holding $130M in PHL benefits slam liquidation, seek to intervene

- Elevance making difficult decisions amid healthcare minefield

More Life Insurance News