Today’s selling and buying environment requires new standards

Our country and its life insurance industry have experienced phenomenal growth since the turn of the last century. During the 20th century, we saw such interruptions as a 10-plus-year economic depression, two world wars and numerous foreign conflicts. From the 1905 Armstrong investigations to the era of “Father Knows Best” to the time just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancies in the U.S. have risen from an average of 49 years in 1905 to 79 years in 2020 — a 68% increase.

In 1905, $5 billion in life insurance death benefits were in force. By 2020, that number grew to $20.4 trillion (a 4,080-fold increase). By almost any measure, that’s progress.

Not so progressive are sales practice issues that seemingly move the industry three paces forward and then two paces (or four) back, reflecting the awkward and tenuous move away from “caveat emptor” and toward fiduciary standards of care. This is the ebb and flow of the issues reviewed in last month’s InsuranceNewsNet article “The Game of Life.”

There has been a growing concern for providing enhanced consumer protection in the purchase of increasingly complex annuities and life insurance products. This concern was prompted by the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act’s attempt to harmonize agent and broker sales behavior with that of fiduciaries. Concerns further increase with the existence of extremely high and upfront sales compensation. After all, doesn’t compensation drive sales behavior? But compensation won’t change anytime soon, notwithstanding attempts in the specialty area of “no-load” products.

Major regulations and rules impacting certain groups of advisors

1. Following the passage of the 1974 Employee Retirement Income Security Act, the Department of Labor attempted to broaden the extent to which advisors selling products or services to retirement plans would be deemed to fall under strict fiduciary standards. Implemented in 2015, the DOL’s updated fiduciary regulation was vacated by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit in March 2018.

“DOL 2” was instituted in 2021. Both efforts were an attempt to impose fiduciary duties on those receiving fees and/or commissions when rendering financial advice and/or making product sales to retirement plans, expanded to include individual retirement accounts and Roth plans.

2. In 1979, the Society of Financial Service Professionals began requiring applicants to agree to abide by its Code of Professional Responsibility as a condition of membership.

3. In 2019, the CFP Board of Standards upgraded its fiduciary standards to require that all client discussions and planning performed by a CFP certificant be performed at a fiduciary level.

Unstated, though implied, is that if something should have been discussed in the planning process but wasn’t, the CFP may be in jeopardy of a complaint or lawsuit in the event that a client claimed the CFP’s failure to provide advice created financial loss for the client.

This is probably most important in the area of personal risk planning, something many non-insurance advisors do not provide.

4. New York’s Regulation 187 went into effect for life insurance sales in New York state in early 2020, imposing “client best interest” and suitability requirements on agents and brokers in the sale of cash-value and term life products as well as annuities. The regulation was suspended by the Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court in April 2021 and is now under appeal to New York’s Supreme Court. Most life insurance companies selling in New York continue to require agents and brokers to follow the broad requirements of the suspended regulation.

5. Also in 2020, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority introduced Reg BI to address client best-interest issues. While some commentators suggested Reg BI didn’t go as far as the requirements of the DOL or the CFP Board of Standards, it was at least an important first step. FINRA has already audited and assessed some fines for failure to meet the new standard.

All of these reflect current regulatory imperatives, addressing producer behavior by those who fall under various regulatory purviews. However, the broader question must be asked: What is the advisor’s responsibility to the client when it is merely a matter of ethical and professional imperatives?

Clerks are largely regulated by rules, generally with clear do’s and don’ts. Professionals are regulated by principles-based processes and procedures. These make it inherently more difficult to judge deficiencies in individual situations that may change the objective viewpoint.

Organizations weigh in

Finseca occasionally coauthors position papers with trade groups such as the American Council on Life Insurance. Finseca has a broad mission to protect the interests of agents and advisors, and as a result, it generally provides pushback as the counter to the pull for more regulatory sales practice solutions.

The Life Insurance Consumers Advocacy Center is a California state-focused not-for-profit entity with the mission to create greater transparency in life and annuity sales practices, especially in the area of “investment-focused” product sales. The need for LICAC and similar financial watchdogs is one of the more recent reflections of the broader issues first raised by Dodd-Frank and ending with New York’s Regulation 187.

Today’s issues — front and center

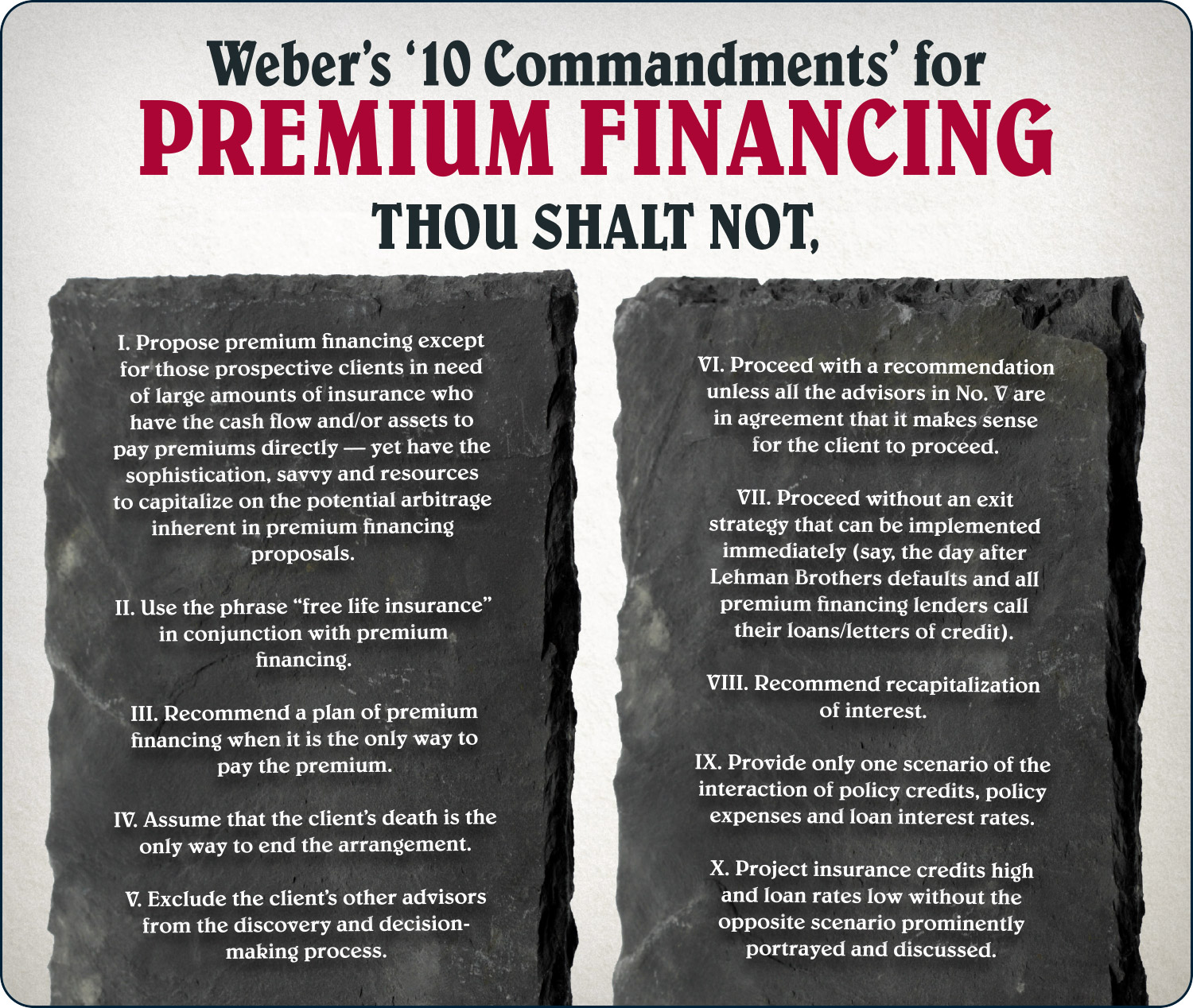

1. Premium financing (using borrowed money to pay life insurance premiums) has existed for a number of years, but the volume and breadth have increased markedly in the past five to 10 years. The concept works under the premise that policy values will increase at a greater rate than loan interest, along with the expectation that such loans will ultimately be extinguished by policy values.

At the same time, it is assumed the client has the means to pay premiums but has more profitable opportunities, especially in times of low borrowing rates.

In reality, however, there isn’t a good probability the policy sales illustration will deliver the expected benefits after an objective analysis using appropriate statistical measurements of the stock market’s financial ups and downs. Along with the maxim first stated by Aristotle, loosely stating, “We are drawn to the attractive impossibility rather than the less attractive probability,” we are currently in a market downturn in which indices and current segments are generally at 0% guarantees, while loan interest rates are rapidly rising. Adding to the concerns about these plans are the instances of loan commitments that are greater than the borrower’s net worth.

2. Life insurance enjoys federal and state income tax advantages not accorded most asset classes.

These tax benefits were created with widows and orphans assumed to be the primary beneficiaries of life insurance. But these tax benefits are now being sold to wealthier clients for whom tax benefits are the primary — not secondary — feature.

Rising income tax rates, or at least the possibility of higher rates, prompted agents to promote the tax advantages of tax-deferred policy cash-value buildup and the subsequent absorption of those deferrals into tax forgiveness upon payment of the death benefit.

3. We recently saw a prominent financial newsletter pitch for the many benefits of a Tax-Free Retirement Account — a description free of any allusion to insurance, yet the underlying product is a life insurance policy. The idea is to suppress the death benefit component of cash-value life insurance to the greatest degree possible in favor of maximizing tax-deferred accumulation of cash-value and “retirement income” policy loans.

The typical illustration can show more than 4-to-1 tax-free cash flow — ostensibly for retirement — compared to the “premiums” paid in the earlier years. However, because these products are so complex, it is highly unlikely illustrated expectations will be met. Carrier control over many of the switches and levers of policy credits and debits, and policy sales illustrations with constant rate assumptions make it inherently both volatility and the carrier’s control over key factors affecting the actual outcome of the proposed benefits and costs.

4. The newest twist on a “tax-free retirement account” occurs when the benefits are proposed through premium financing.

The bottom line in most cases is “It ain’t gonna happen,” potentially leaving the client with previously deferred policy gains subject to ordinary income taxes in the year the policy lapses.

5. In most of these new trends, policy illustrations — primarily for indexed universal life — are becoming the main thrust of the sale, with almost total dependence on the sales proposal rather than understanding how the policies work in the face of volatile stock market returns. The most likely result is it’s unlikely the illustrated expectations will be realized. It is not that the IUL is “bad.” But in a number of cases, the client is not given the full picture of the possibility the scheme will not work out as “illustrated.”

6. Remember all those wonderful tax benefits accorded to life insurance policies? There is a contingency rarely mentioned: The insured must die with the policy still in effect and paying a death benefit. If the policy is surrendered or lapses before it becomes a death benefit, there is immediate ordinary income taxation on any gains in the policy in excess of the policyowner’s basis.

According to a 2016 academic paper by Daniel Gottlieb and Kent Smetters, “nearly 88% of universal life policies ultimately do not terminate with a death benefit claim,” hence, taxes accelerate on all those previously untaxed policy gains.

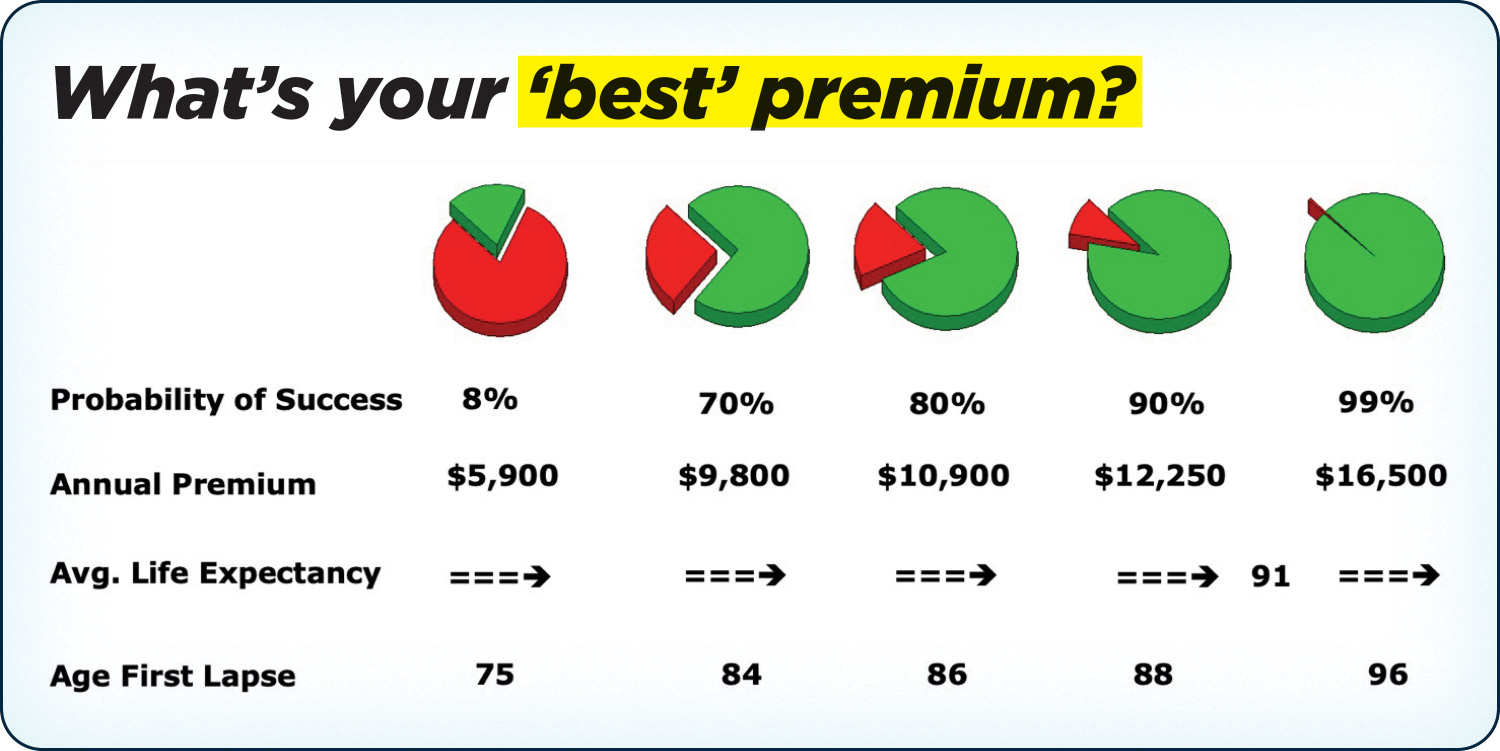

7. Since the introduction of current assumption/universal life products, the typical buyer’s almost universal objective is to pay only the lowest possible premium. In many cases, this causes the client to sort through different policy illustrations to seek the lowest price.

But many of the factors resulting in a calculation of a planned (not guaranteed) premium are in the control of the agent running the illustration software. A planned premium is not the premium. The correct premium is the one that will sustain the policy until the insured person’s death, whether that’s in five years or in 50 years.

The policy must be assessed periodically to make sure that the correct premium is being paid for all the inevitable changes that will occur in various policy debits and credits that occur as time goes on.

Chasing the initial appearance of “best price” does not and cannot assure the buyer their policy will have a high probability of being in force whenever death occurs. We need a new paradigm for “Goldilocks premium funding”: not too much, not too little — but just right.

8. Rather than seeking the lowest price, the better paradigm is for the buyer to consider the minimum probability of success they are willing to accept for the insurance policy and its duration. Does a 50-50 flip of a coin represent a sufficient probability? Hardly. Most clients — including those of great wealth — typically want a probability of success of at least 80%, 90% — even 100%.

With that vital insight, the calculation of a universal life premium then can be made by determining the current payment that will meet that probability threshold. After two or three years, the policy should be reevaluated based on current account values and other changes that may have occurred. This periodic reassessment process should be deployed throughout the insured person’s life.

A new paradigm and a new management strategy

As readers can see, the originally solved best premium in this example has less than a 10% chance of sustaining to age 100. This client’s average life expectancy is age 91. In this case, the best premium produces unacceptable odds of success.

Alternatively, armed with this information, few clients (and their agents) would be willing to take a chance that the best premium will sustain the policy to whenever death occurs. A client wishing to ensure the availability of the policy’s death benefit regardless of the many ups and downs likely to occur in a lifetime will need to use the probability of success paradigm for effective lifetime management of their policy.

OK to buy life insurance with intent to resell it, Georgia court rules

Aflac reports earnings hit, but Wall Street takes it in stride

Advisor News

- As tariffs roil market, separate ‘signal from the noise’

- Investors worried about outliving assets

- Essential insights a financial advisor needs to grow their practice

- Goldman Sachs survey identifies top threats to insurer investments

- Political turmoil outstrips inflation as Americans’ top financial worry

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- AM Best Comments on the Credit Ratings of Talcott Financial Group Ltd.’s Subsidiaries Following Announced Reinsurance Transaction With Japan Post Insurance Co., Ltd.

- Globe Life Inc. (NYSE: GL) is a Stock Spotlight on 4/1

- Sammons Financial Group “Goes Digital” in Annuity Transfers

- Somerset Reinsurance Announces the Appointment of Danish Iqbal as CEO

- Majesco Announces Participation in LIMRA 2025: Showcasing Cutting-Edge Innovations in Insurance Technology

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

- IBX had a $239 million net loss in 2024, its first red ink since 2015

- Mercy Health, Cigna reach agreement

- Letter: Bentz does nothing to protect SSA, other programs

- Letter: Bentz does nothing to protect SSA, other programs

- Idaho Senate approves Medicaid budget

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News

- Proxy Statement (Form DEF 14A)

- Insurance leaders say AI a top imperative but struggle to deploy it

- Proxy Statement (Form DEF 14A)

- Proxy Statement (Form DEF 14A)

- 5 steps to overcome mistrust in life insurance sales

More Life Insurance News