The increasing demand for standards of care in the sale of life insurance: ‘Back to the Future’

It’s 10 p.m.; do you know where your policies are?

In 2020 alone, $3.33 trillion of death benefit was sold, although there is an anecdotal sense that as much as 50% of those sales was policy replacements rather than entirely new benefits.

It’s also worth noting that 2020 sales were achieved in an industry in which the number of life insurance companies was one-third that of 1988, the year in which the number of life insurance carriers was at its peak.

A further intriguing fact: The life insurance industry’s payments on behalf of beneficiaries, annuitants and other recipients of benefits from their policies (including health insurance) totaled $678 billion in 2020. This figure is second in total distribution only to the Social Security Administration’s Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund payments of $993 billion that year.

A final sobering statistic: In a previous article, I cited a 2016 academic paper by Daniel Gottlieb and Kent Smetters in which they tallied “… nearly 88% of universal life policies that ultimately do not terminate with a death benefit claim.” There is a significant mismatch between the need for life insurance products as expressed by the amount sold — and the proportion that will ultimately pay a death benefit. Lapses or exchanges that result from a mismatch of client needs and resources with the products sold, as well as agents who do not help actively manage those products, give rise to concerns about standards of care in the sale of life insurance.

It is easy to lay the problem on universal life-type policies, which were first introduced almost 45 years ago. But it is not the product’s fault; it’s a matter of how UL is sold and managed as well as the reasonableness of expectations conveyed to the buyer in the process of selling such a policy.

That said, the “pay what you want to pay when you want to pay it” sales mantra that propelled UL sales statistics to more than 40% of permanent insurance sales by 1985 (simultaneously decimating whole life sales during the same period) quickly devolved to “pay as little as you want (or nothing) as infrequently as you want (or never).”

Once again, anecdotally, very few of the UL policies sold in the 10 years after the product was introduced still are in force. Sure, there were some premature deaths prompting payment of death benefits for policies sold in that early period. But for the most part, as current interest rates in the U.S. economy began their 40-year downward spiral from the peak in late 1980, the focus on new sales (and replacement sales) began shifting to policies that could benefit from a revived stock market — in no small part due to falling interest rates.

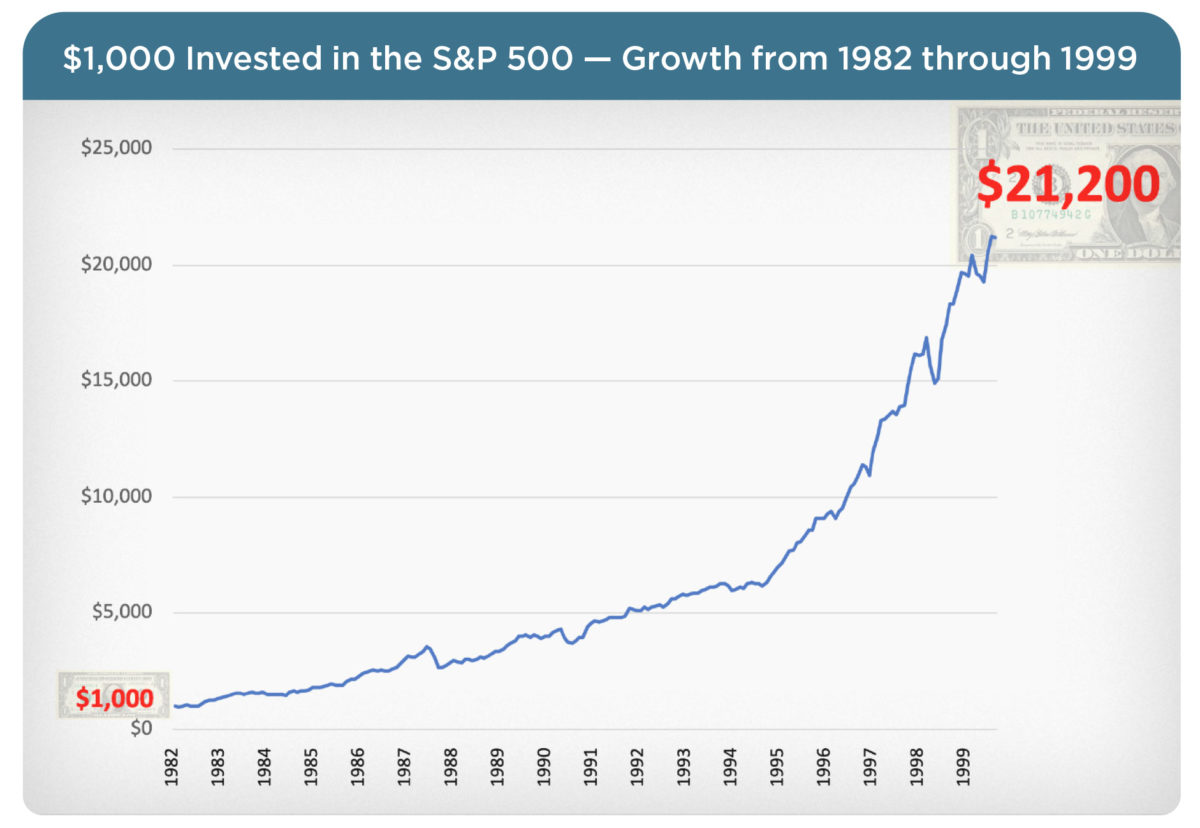

As stock market returns began accelerating in the mid- to late 1980s, variable universal life became the product “du jour,” especially because VUL policies could be illustrated at a constant annual gross rate as high as 12%.

Despite robust increases in the S&P 500 (e.g., up 37% in 1995), a very different product began to take hold in the marketplace by the mid- to late 1990s. Instead of attempting to accumulate cash value during a booming stock market to some degree propelled by “vaporware” and high-tech public offerings, no-lapse guaranteed universal life (NLG) was oriented to a specific premium that would guarantee the policy would remain in effect even if the account value fell to $0.

By the market slump beginning March 2000, VUL was “out,” and NLG was “in.” And then came the Great Recession, shortly after which NLG was out and indexed universal life was in. Looking back, we’ve seen four 10-year cycles in the generational evolution of current assumption universal life products, from UL to VUL to NLG to IUL. What’s next? Back to basics!

Where do we go from here?

Statistics suggest U.S. households are significantly underinsured against loss of income due to disability or premature death. According to LIMRA, there are 106 million Americans, representing 41% of the adult population, who acknowledge they are living with a life insurance coverage gap. Some losses can be insured; some cannot!

With respect to wage loss that can be insured, less than three years of coverage for lost income due to premature death (or income shortfall in the event of disability) leaves families exposed to a significant loss in their standard of living compared to a time when two wage earners were contributing.

In a recent Insurance Barometer survey, respondents were asked about their expectation of financial hardship in the event of the primary wage earner’s death. Ten percent said they would feel the financial impact within one week. Forty-four percent expected hardship would occur within six months. Only one in five responded they would feel hardship in five years or more, and nearly as many, 17%, did not know how long it would take to experience hardship.

It’s a simple but essential issue: People need to buy — and agents need to sell — a lot more life and disability and long-term care insurance. For these needed increases in coverage, we would anticipate new policy placements to follow the current in-force “term/perm” proportions of 70% term life insurance and 30% of some form of permanent coverage.

The good news is that it should be easy for a financial professional to help prospects understand and choose to do something about the deficits in their personal risk planning. The real question is how to do this with the reality that selling standards are likely to continue the current upward trajectory of agent responsibility. This can leave agents concerned about how to make the transition to those higher standards.

There is a fundamental need for buyers to be provided suitable advice and suitable product recommendations. And that is the reality coming from an increasing array of regulations, legislation and obligations to professional organizations. Although these authorities cast a wide net of obligation to suitability and client best interest, agents who sell life insurance have been largely exempt from an obligation to suitability — much less client best interest — unless they also fall within one of these other overseeing authorities.

While it is one thing to be obligated to make suitable product recommendations, what does that mean in the real world? How can insurances agents do the right things right as they look to the future of sales, service and interactions with new prospects?

Two approaches for the future of suitability and best interest

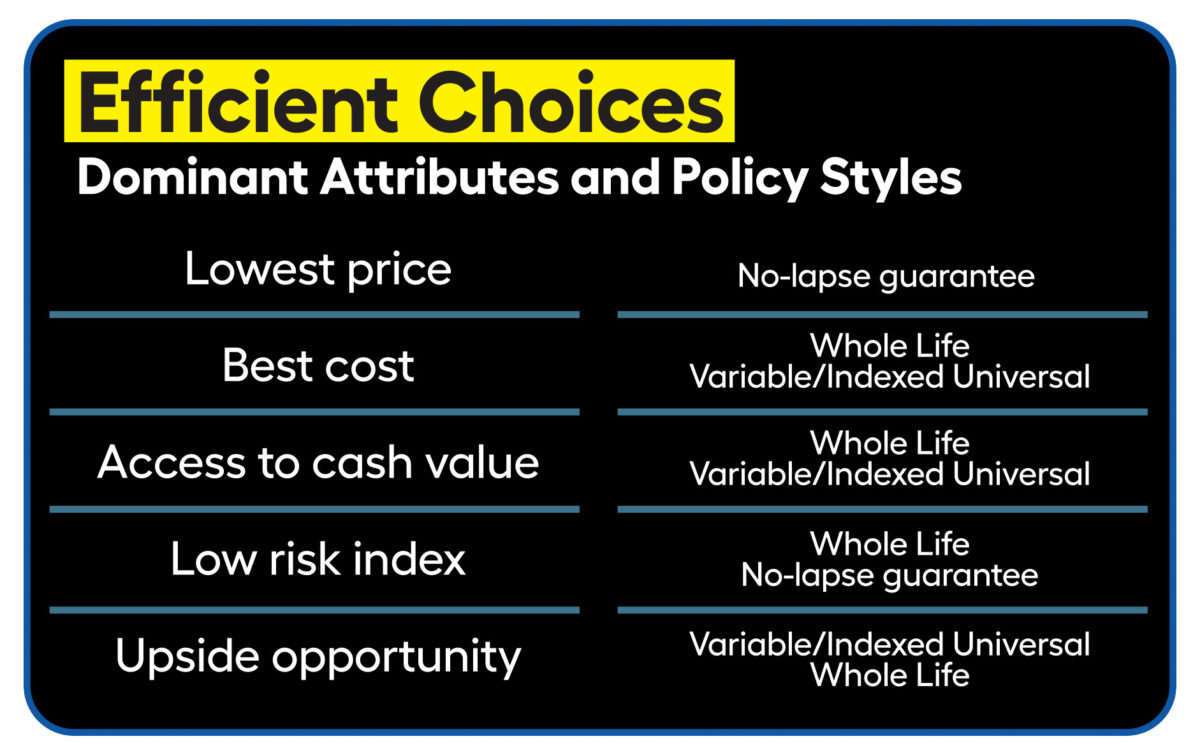

The first approach relates to policies designed for a lifetime. The fundamental concept here is that a client’s risk tolerance is the best guide to suggest the type of policy that will fit their needs and be compatible with their general approach to managing their money — suitably and in their best interest.

We know that life insurance policies fall into two broad design categories: policies with guaranteed premiums, and policies with flexible premiums that are not guaranteed. Once we help the client discover their inherent risk tolerance, it’s then possible to use that risk tolerance to suggest a life insurance policy style that feels natural based on what drives the growth in cash values as the primary long-term resource to sustain the policy:

» A conservative risk tolerance suggests recommending only policies with guaranteed premiums, since the inherent risk statement is “I am intolerant of volatility and seek guarantees.” Such policies include participating whole life, level premium term, and NLG or VUL with a no-lapse feature, with an understanding that for such a policy to retain its guarantees, specified premiums must be paid on time and cannot be “skipped,” and there is limited or no access to cash value without potentially losing the underlying guarantee of policy sufficiency to a specified age.

» A balanced risk tolerance can suggest recommending policies with flexible premiums, with the inherent risk statement “I am tolerant of modest volatility and willing to accept fewer guarantees in favor of premium payment flexibility.” UL and simple IUL policies can be suitable recommendations.

» An aggressive risk tolerance — if clients are comfortable with risk-taking and investments that may go up or down in the short term — they may be compatible with the risk statement “I’m tolerant of volatility and willing to do without guarantees in favor of premium investment opportunity.” This describes VUL, and the agent must be additionally licensed to sell variable insurance products.

» The final risk statement is somewhat contrived from the misleading sales slogan of “zero is the hero” on behalf of IUL designs. Thus, with tongue in cheek, I suggest the risk tolerance of “passive aggressive” to be compatible with “I’m intolerant of volatility but drawn to the idea of upside with no downside.”

There is potential downside to indexed products. Still, seeking some positive upside with no negative crediting downside can be an acceptable approach to policy design for this risk tolerance, as long as the client understands that the policy needs periodic management for premium adequacy over the life of the insured.

In all instances of non-guaranteed premium designs, it is incumbent on the agent or planner to explain to the client:

» The illustration is not the policy.

» The illustration is not a projection of likely outcome.

» The illustration is designed to show how the policy works in one particular and arbitrary scenario of constant returns and no changes to the original scale of nonguaranteed underlying policy expenses.

» The illustration is primarily intended to differentiate between policy guarantees (usually on the left side of the ledger) and what is not guaranteed (on the right side of the ledger).

The second approach builds on the concept that a client’s risk tolerance can be a fundamental means to determining a suitable policy style that is in the client’s best interest. My firm’s fee-only process to life insurance policy style recommendations often results in developing a customized portfolio of policies.

Readers probably don’t see much “portfolioization” yet in the marketplace, but I suggest it may be an important differentiator when you consider: if an asset allocation calls for diversification between different asset classes for the long-term health of an investment portfolio, why wouldn’t the same concept apply to assembling different styles of life insurance policies?

We have diverse policy styles that are uncorrelated to the stock market (whole life, term and no-lapse products) as well as the popular IUL and VUL-styles that are directly or indirectly driven by the stock market.

Consider the conceptual attributes — with strengths and weaknesses — of today’s different styles of policies:

» We know we are naturally drawn to the lowest premium, while at the same time we seek guarantees; these are often incompatible expectations.

» What if death benefits are worth less (due to inflation) over a long life expectancy? Within some UL products, the buyer can incorporate an increasing death benefit option — but with the peril of leaving it in effect for too long — when the cost of insurance expenses can become so high as to force a lapse before death.

» Does the client need access to policy cash values? Or does the client need natural increases in the death benefit, as exists with participating policies and paid-up additions?

» Should there be a mix of equities and fixed assets driving the cash value — and therefore the likely sustainability of the policy — for the policy’s financial health.

These are largely incompatible objectives; not all can be derived from just one style of policy. But they can be achieved with a custom-proportioned use of an appropriate array of policies such as whole life, VUL, IUL and NLG with their respective and partially overlapping attributes.

Using the matrices

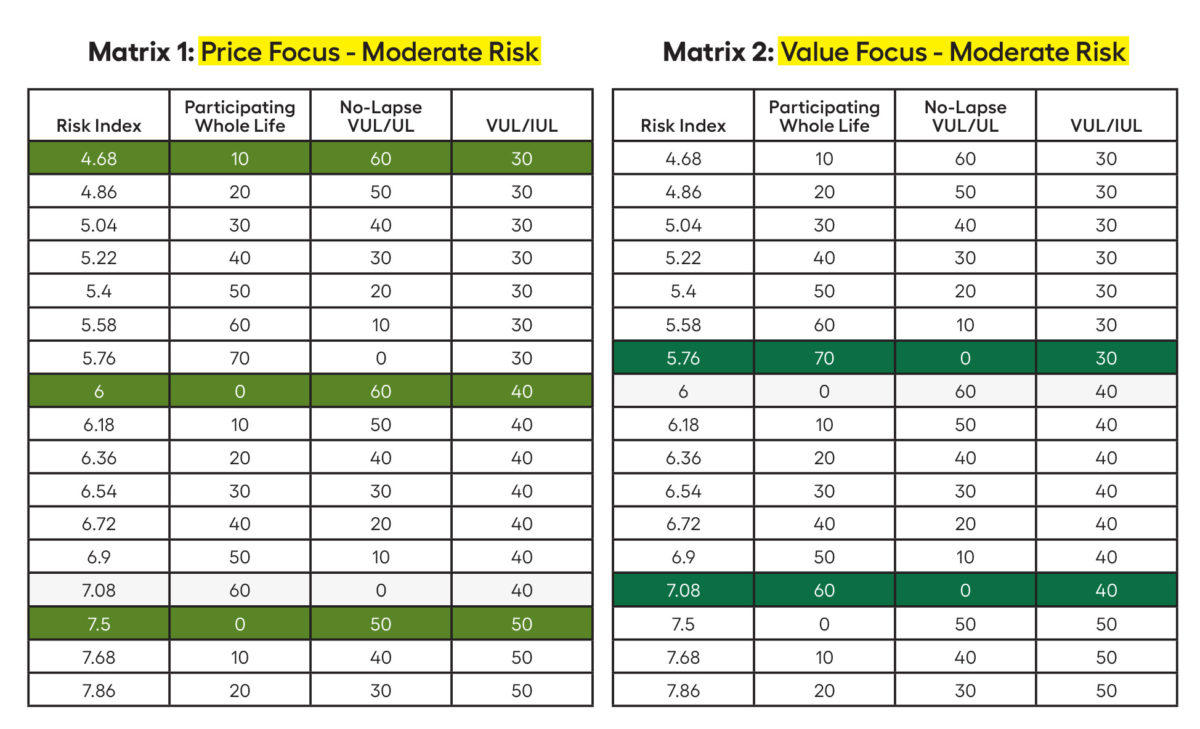

By understanding the client’s overall risk tolerance — and assuming that tolerance would also be relevant to a portfolio of policies — consider the degree of “price orientation” versus “value orientation” a client might have with regard to a potential portfolio of insurance policies.

For the following example, let’s assume a client’s risk level of 7.5 — the middle of the extremes between ultraconservative and very aggressive investing. Looking at Matrix 1 and finding the 7.5 risk index tolerance factor on the left side of the chart, you can see the potential risk-driven proportion of no whole life, 50% NLG, and 50% VUL or IUL. This is the starting point for considering a portfolio through the client’s lens of singularly price-focused concerns.

Matrix 1 shows three highlighted “portfolio” allocations that can be a useful starting place to find a price-focused portfolio of policies within gradations of moderate risk.

On the other hand, if the client is value-focused (when the client’s primary consideration is availability and access to policy cash value, as well as the potential for increasing death benefits over time), we would look to Matrix 2. These three highlighted matrix entries entries maximize value — in the second instance, 60% whole life and 40% IUL/VUL — with the additional benefit of conveying a slightly lower risk index of 7.08.

Client’s best interest can be defined as the attitude an agent or planner brings into the client/advisor relationship. The Society of Financial Service Professionals expresses that attitude primarily through a variation on the golden rule: “I will provide the same advice to a client I would take for myself when in similar circumstances.”

Suitability is likened to fit. “Does this plan — or investment product or policy — fit in the larger picture of how I comfortably use my money and invest my resources?”

In this three-part series focused on the increasing demand for standards of care in the sale of life insurance, I’ve attempted to convey an understanding of why the characteristics of best interest and suitability are not just needed but also can be a differentiating approach to serving the client community and attracting more prospects through the consultative sales approach. It is possible to do the right thing and thrive in the process!

Help clients understand rising long-term care costs

An Advisor who ‘Rocks’ — with Bryon Holz

Advisor News

- Guardian releases The 2024 Guardian Annual and record-breaking financial results

- Worker retirement confidence unchanged, retirees more optimistic

- TIAA, MIT Age Lab ask if investors are happy with financial advice

- Youth sports cause parents financial strain

- Americans fear running out of money more than death

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

Health/Employee Benefits News

- Legislative work continues despite the lack of a state budget

- There are ways the state keeps insurers in check while assisting consumers

- Bill aimed at holding health insurance companies accountable moves forward

- North Dakota Gov. Kelly Armstrong signs bill to put checks on AI health care decisions

- 2024 Annual Report

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News

- Annual Report for Fiscal Year Ending December 31, 2024 (Form 20-F)

- 1Q 2025 financial supplement

- AM Best Affirms Credit Ratings of Misr Life Insurance Company

- AM Best Removes From Under Review With Negative Implications, Affirms Credit Ratings of Germania Farm Mutual Insurance Association and Core Subsidiaries; Assigns Positive Outlooks

- Guardian releases The 2024 Guardian Annual and record-breaking financial results

More Life Insurance News