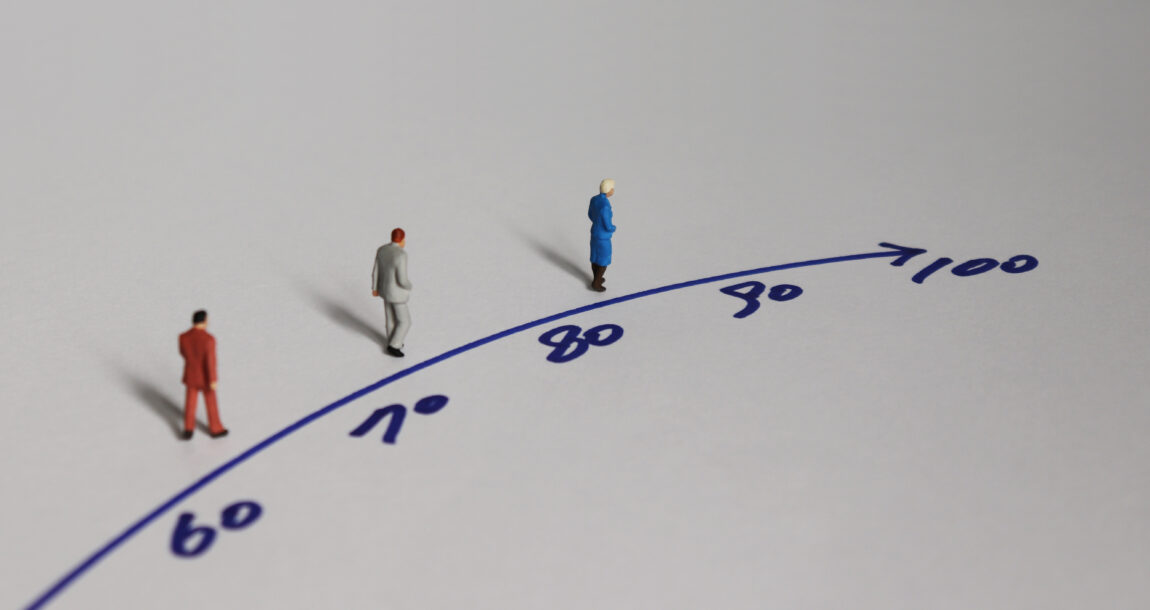

Health-based actuarial longevity: The starting point for retirement planning

For the 5% of those over age 60 without a chronic health condition, actuarial data show the odds of living to 95 are only 1 in 5. For the 30% of retirees with diabetes, the odds of reaching this age are less than 1%.

Given the likelihood of reaching this milestone, we need to ask whether the commonly used industry “rule of thumb” of planning to age 95 makes sense for all clients.

Low probability does not mean no probability. Longevity risk gets a lot of attention, but the other side of the coin - the high probability of dying earlier than 95 – should also be discussed with clients.

Given the financial consequences of longevity, using health-based actuarial data as a starting point for planning discussions with clients not only makes sense, but is consistent with best-interest standards.

To calculate actuarial longevity for individual clients, data around the two most significant predictive determinants of longevity - sex at birth and health - must be incorporated into projections.

Underscoring the importance of both factors, projected longevity for a healthy 65-year-old male is 88, and for a healthy female 90. If the male has high cholesterol, he will live on average to 85, and a woman to 87. If he has type 2 diabetes, he will live on average to 78, and a woman to 82.

Since clients with serious health conditions already know that their chances of living to 95 or beyond are low, sharing realistic longevity expectations is rarely a surprise or shock. In fact, our experience shows when data is seen as credible, clients are more likely to engage and take action.

Health-based actuarial longevity should be seen as a foundation for conversations about the savings needed in retirement, the potential to spend more annually and how to address the needs of a surviving spouse, as well as the legacy they may want to leave. It also provides a data-based benchmark for thinking about longevity risk, adding additional years to the lifespan used for planning, as well as product discussions to address the risk of living longer than expected.

As we detail in our white paper on health-based longevity, the financial impact of planning for a shorter or longer lifespan is significant. A 65-year-old male who has met his savings goals to fund income needs through age 95, but who has a diagnosis of diabetes adjusts his plans to his average actuarial longevity of age 79. This would potentially give him $700,000 more to spend in retirement or allocate for different purposes.

Longevity planning is often positioned as a zero-sum game – it is not. One common view is that if there’s any possibility a client will be alive at 95, then they should plan for it. Using actuarial longevity or even a few years longer will, however, not mean that the client will go from 100% of the income they will need to zero.

With a combination of Social Security, guaranteed income products, and longevity insurance in the form of qualified longevity annuity contracts, advisors have the tools to balance clients’ financial goals and longevity risk. Increased spending through retirement or planning on leaving more to heirs based on a shorter lifespan and then drawing the longevity lottery ticket, may mean less income will be available later in life, not no income. As with all things retirement, there are trade-offs and balances to be struck.

Advisors have a responsibility to draw on science-based fact – the best available actuarial data. Since this data is updated on an annual basis and clients’ health will change over time, updating longevity expectations should be part of the annual financial plan review process to ensure that planning goals remain aligned with changing health and other personal circumstances.

Ultimately, the answer to the question of whether advisors should use 95 as a default for planning purposes is like most retirement planning issues, nuanced.

For heathy young people in the early stages of their working careers, actuarial longevity projections show they will likely live into their early 90s. Saving to live to 95 or even beyond makes sense; the more money they will have for retirement, the better.

For clients approaching retirement, health condition becomes increasingly important to the longevity they can expect, which should impact planning decisions made during the decumulation phase. When living to age 95 is a low probability, setting more realistic goals offers the potential for a better quality of life or making sure other financial priorities are realized.

Health-based actuarial longevity calculated for individual clients provides a data-backed approach to balance retirement spending and longevity risk, allowing for suitable product choices to ensure that income will be available through retirement.

Ron Mastrogiovanni is CEO of HealthView Services. Contact him at [email protected].

© Entire contents copyright 2024 by InsuranceNewsNet.com Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reprinted without the expressed written consent from InsuranceNewsNet.com.

Ron Mastrogiovanni is CEO and chairman of HealthView Services. Ron may be contacted at [email protected].

National Life Group is a ‘progressive mutual,’ CEO says, with record sales

Federal appeals court to hear ESG rule arguments in July

Advisor News

- SEC in ‘active and detailed’ settlement talks with accused scammer Tai Lopez

- Sketching out the golden years: new book tries to make retirement planning fun

- Most women say they are their household’s CFO, Allianz Life survey finds

- MassMutual reports strong 2025 results

- The silent retirement savings killer: Bridging the Medicare gap

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- Annexus and Americo Announce Strategic Partnership with Launch of Americo Benchmark Flex Fixed Indexed Annuity Suite

- Rethinking whether annuities are too late for older retirees

- Advising clients wanting to retire early: how annuities can bridge the gap

- F&G joins Voya’s annuity platform

- Regulators ponder how to tamp down annuity illustrations as high as 27%

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

- Blue Cross Blue Shield of Wyoming CEO Gore announces retirement; Urbanek to take lead

- Wellpoint taps Rachel Chinetti as president

- Proposed changes to MA and Part D would harm seniors’ coverage in 2027

- Pan-American Life Insurance Group Reports Record 2025 Results; Premiums Reached $1.86 Billion and Net Income Totaled $110 Million as Company Enters Its 115th Year

- LightSpun and Smile America Partners Announce Partnership to Accelerate Dental Provider Enrollment to Expand Treatment for 500K Underserved Kids

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News

- Annexus and Americo Announce Strategic Partnership with Launch of Americo Benchmark Flex Fixed Indexed Annuity Suite

- LIMRA: Individual life insurance new premium sets 2025 sales record

- How AI can drive and bridge the insurance skills gap

- Symetra Partners With Empathy to Offer Bereavement Support to Group Life Insurance Beneficiaries

- National Life Group Ranked Second by The Wall Street Journal in Best Whole Life Insurance Companies of 2026

More Life Insurance News