Harvard study: how poor people stay poor – and how to fix it

It’s who you know – that is the old chestnut on how to be successful in life, but it turns out it’s also where you grow that determines economic mobility.

A massive study examining 70 million Facebook users’ 21 billion relationships showed that a poor person’s ticket to upward mobility is to know rich people. Seems simple, but it is more than just collecting contacts – it requires an economically diverse community and a low bar to making connections.

Raj Chetty, a Harvard economics researcher who specializes in big data studies, pulled together a team of 20 researchers that resulted in two articles on social capital published this week in the journal Nature.

The findings harken back to the Jim Rohn quote, “You are the average of the five people you spend the most time with,” although the effect stretches back to childhood. Among other things, the study showed that if poor children grew up in places where 70 percent of their friends were from higher-income families, they tended to have a 20% boost of their future income.

So, success is not just pulling on one’s own bootstraps, but having those boots in a community of wealthier people. This is why people born, reared and educated in poorer communities have a far smaller chance of moving up the socioeconomic ladder.

Researchers used three types of social capital in their study: economic connectedness, the degree to which low-income and high-income people are friends with each other; cohesiveness, the degree to which social networks are fragmented into cliques; and civic engagement, rates of volunteering and participation in community organizations.

It turned out that economic connectedness was the most important of the three, although the others are also important. The first necessary condition is exposure – the presence of high-socioeconomic status (SES) friends.

The researchers mapped the results across the United States in every neighborhood, high school and college. You can find the percentage of high SES friends in your area here.

But exposure alone is not enough. The highest hurdle is the friending bias, or the tendency of high-SES people to befriend low-SES people. If poorer people cannot make connections with richer ones, the exposure is not enough.

“We show that exposure and friending bias each account for about half of the social disconnection between people with low versus high SES,” according to the article. “Like exposure, friending bias is shaped by institutional structure, such as the size of groups and the settings in which people interact.”

For example, the research showed that low SES people can make friends with high SES people in schools that show a low level of friending bias. But if the institution has a high friending bias, intervention might be necessary, such as increasing social interaction across class lines within the neighborhood or school.

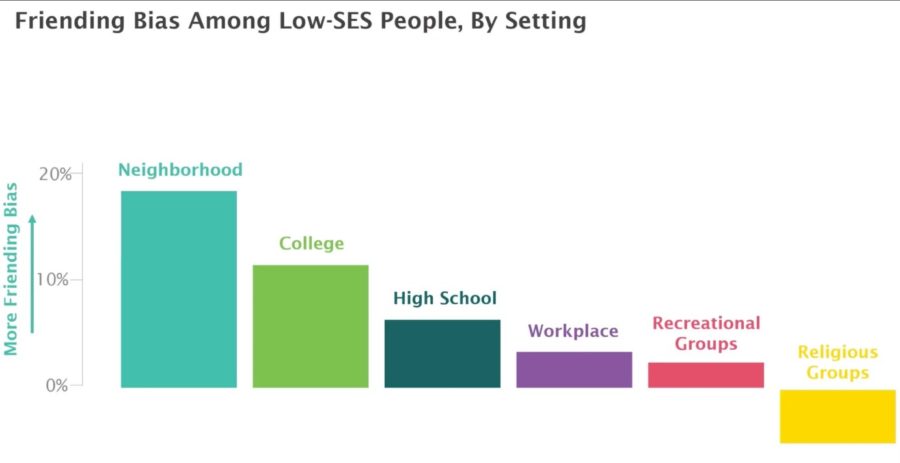

Just as exposure of poor people to rich people is not enough for socioeconomic mobility, a low friending bias also is not sufficient without the exposure. An example of this is religious organizations, which have the lowest friending bias, but they tend to be economically segregated.

Friending bias is also lower in workplaces and recreational groups. It is highest in neighborhoods, probably because residential segregation within zip codes limits opportunities for contact and interaction, according to the researchers.

Colleges have a higher friending bias, but digging into the data shows the balance between exposure and friending bias.

The setting is an important factor because the research showed that a person who might show a high friending bias in one place might be perfectly friendly in another.

How to rebalance

Researchers said exposure and friending bias can be corrected by policy changes. Integrating institutions along high and low SES lines is a start for increasing exposure is a start. But it is not enough, as some of the nation’s efforts to integrate schools show. Integration is not effective without lowering the friending bias.

Interventions to lower friending bias have not been studied extensively, the researchers wrote. But there have been some examples of these kinds of interventions.

Rearrange segregation: Even integrated schools have segration, such as Berkely High School. That school is socioeconomically diverse but the 3,000 students are split into five learning communities that a Facebook user said caused “implicit segregation, resulting in student learning communities with separated concentrations of white students and students of color,” according to the article. In 2018, the school began assigning ninth-graders to small, intentionally diverse “houses” or “hives,” changing how students are tracked and reducing the size of the groups.

Restructure space and urban planning: The structure itself might lead to segregation within diverse institutions. Lake Highlands High School in Texas has a high level of friending bias. In that case, the architecture led to low cross-class interaction because of structures such as the three lunchrooms, where students clustered depending on their social group or options for low-cost and free lunches. Part of the school’s restructuring is to create a single lunchroom. Even though students may still gather in cliques, they will have more opportunities to interact.

“Architecture and urban planning could have a role in reducing friending bias outside schools as well,” researchers wrote. “Examples include social infrastructure, such as public libraries, to build social bonds across groups; the effects of public parks on social interactions; and the impacts of public transit on the interactions between people living in different neighborhoods.”

Create new domains for interaction: This is essentially building venues and programs that encourage cross-SES interaction. The researchers used Inner City Weightlifting in Boston as an example. The gym recruited personal trainers from a lower-income background to train wealthier people. The gym’s founder, J. Feinman, said the effort not only gave the trainers more income, but it also changed the power dynamic and created genuine inclusion.

“The people in our program gain access to new networks and opportunities,” Feinman said, “while our clients gain new insights and perspectives into complex social challenges.” Feinman added that the paying clients started helping their trainers by doing things such as offering job opportunities outside the gym and paying for their trainers’ children to go to summer camp with their own children.

The researchers invited individuals and institutions to review data on their site 0000 to find the level of their own cross-SES exposure and friending bias to help “determine whether interventions to reduce friending bias or efforts to increase socioeconomic diversity are likely to be most valuable for increasing economic connectedness.”

Steven A. Morelli is a contributing editor for InsuranceNewsNet. He has more than 25 years of experience as a reporter and editor for newspapers and magazines. He was also vice president of communications for an insurance agents’ association. Steve can be reached at [email protected].

© Entire contents copyright 2022 by InsuranceNewsNet. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reprinted without the expressed written consent from InsuranceNewsNet.

Steven A. Morelli is a contributing editor for InsuranceNewsNet. He has more than 25 years of experience as a reporter and editor for newspapers and magazines. He was also vice president of communications for an insurance agents’ association. Steve can be reached at [email protected].

IRS escalating attacks on some captive insurance companies

Prudential CEO Lowrey: We’ll manage life business ‘very, very carefully’

Advisor News

- Overcoming the indecision of prospects

- What issues top consumers’ list of financial goals for 2025?

- 3 issues investors must be aware of in 2025

- More Americans plan to focus on finances in 2025

- Americans’ saving, investment product savvy improves, study finds

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- Sapiens wins XCelent award for Customer Base and Support for UnderwritingPro for Life & Annuities

- SB 263 expected to bring chaos to Calif. insurance, annuity sales come Jan. 1

- Lincoln Financial hires industry veteran Tom Morelli as Vice President, Investment Distribution

- Structured settlements protect young injury victims | H. Dennis Beaver

- MetLife Inc. (NYSE: MET) Highlighted for Surprising Price Action

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

- Insurers Continue to Rely on Doctors Whose Judgments Have Been Criticized by Courts

- Editorial: Here are our views on new Illinois laws on everything from your health care coverage to your Netflix subscription

- Why filling job openings will be crucial for Connecticut's economy in 2025

- Economists: Rural Uninsured Rates Likely to Rise if ACA Premium Tax Credits Expire

- From Augsta: Approaching deadline to enroll in affordable health care plans

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News

- Exemption Application under Investment Company Act (Form 40-APP/A)

- AM Best Assigns Credit Ratings to Min Xin Insurance Company Limited

- Proxy Statement (Form DEF 14A)

- Prudential Financial Completes Guaranteed Universal Life Reinsurance Transaction With Wilton Re and Completes Internal Captive Restructure

- South Carolina bars A-Cap insurers from writing new policies in 2025

More Life Insurance News