Change Starts From Within

Marcus Creighton delivered results as a MetLife financial securities representative from 2001 to 2014.

The African American advisor secured the largest employer in Missouri as a MetLife client in 2014, according to court documents. A nonprofit health care organization, the client signed up for MetLife’s legal benefit plan and its PlanSmart financial literacy program.

The legal benefit plan alone meant $750,000 in first-year revenue, while PlanSmart opportunities brought the potential for many more millions in MetLife revenues.

Yet, MetLife terminated Creighton later in 2014. In May 2015, Creighton filed a lawsuit in federal court, claiming the company systematically discriminated against its Black employees and ultimately paid them less than their white co-workers.

Creighton claimed that MetLife “almost entirely excludes” Black financial service representatives from forming “favorable” teams when combining client accounts, a common company practice, court documents say. He also alleged that MetLife steered the most lucrative accounts and opportunities away from Black brokers and denied them equal access to the company’s “Delivering the Promise” training program.

A judge approved the lawsuit as a class action and MetLife settled for $32.5 million in July 2017. MetLife denied all allegations and claims asserted, according to the settlement agreement.

“There’s a disconnect in the education and the opportunity,” said Chris Gandy, president and founder of Midwest Legacy Group in Chicago and president of NAIFA-Chicagoland. “In my 22 years being in this business, I’ve led seven companies, seven of the largest companies, in production for a year. And here’s what I can tell you: Never was there a knock at my door for an opportunity for a promotion.”

‘Concerning To Us’

In another case resolved in 2020, Jackson National Life Insurance Company paid $20.5 million to 21 complainants to settle claims in a race, national origin, and sex discrimination and retaliation lawsuit brought by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

The EEOC’s lawsuit, filed in September 2016, charged that Jackson tolerated a work environment hostile to female and African American employees in Jackson’s Denver and Nashville offices. African American employees were referred to as “lazy,” had stress balls thrown at them and were subjected to racially demeaning cartoons, the complaint said.

In addition, a high-level manager referred to multiple African American female employees as “resident street walkers,” the complaint said, and female employees endured sexual comments and leering from male co-workers.

The EEOC’s suit also alleged that Jackson discriminated against African American and female employees in the terms and conditions of employment, such as paying them inferior compensation and regularly passing them over for promotion, and selecting less-qualified white male employees over the complainants.

After the settlement was announced, a Jackson National spokesman said that the company agreed to settle the lawsuit in order to “move forward.”

“While there has been no finding by a court or jury that Jackson violated any laws, we are humbled and recognize that the associates who made claims in this case believe they were not treated fairly or in a way that aligns with Jackson’s core values,” said spokesman Patrick Rich. “This is concerning to us, as it is not consistent with who we strive to be.”

Making The Change

Despite these incidents, many financial services companies are going beyond statements in efforts to become more diverse, especially during the past year. In addition to being the right thing to do, it just makes good business sense.

“Now it is getting that focus and real energy and investment in mindshare at the top of the house,” said Liz Caswell, associate director, markets research for LIMRA/LOMA. “And that’s really accelerating the changes that were already underway, but perhaps at a less intensive level.”

Most insurers have created “business resource networks,” or BRGs, for different minority groups. The BRGs allow for professional growth, resource sharing and discussion on diversity issues. Prudential is a leader in this concept, with BRGs that date to 1993.

Some insurers have set specific goals. For example, Lincoln Financial’s eight-point plan includes a pledge to “grow minority representation at the officer level (assistant vice president and above) by 50% over the course of three years, with a special focus on the Black officer population.”

“We have a responsibility to do far more than raise awareness about difference and inclusion,” said Allison Green, chief diversity officer at Lincoln. “Our responsibility is not just to those who work with us but to our industry, the markets we serve, those who are underserved, and the communities where we live and work.”

Most insurers have diversity directors at the executive level and ramped up hiring efforts in 2020. At American Family Insurance, for example, the company set a bold goal of increasing racial and ethnic diversity by 50% in three years, said Estelle Blockoms, life distribution director for the insurer.

“We believe that focusing on attracting, retaining, developing and promoting a diverse workforce is key to our success in the coming years,” she said during a recent LIMRA Distribution Conference session. “We have it in our focus areas and we have it in our culture statement. It’s a layered approach for leadership all the way down.”

Trickle-Down Effect

There’s a trickle-down effect when Black communities are able to participate in financial planning, retirement planning and all the related benefits, Gandy said. It starts with an advisor force that mirrors those communities, he added.

“My history has been that there was never a minority or diversity individual who walked into my house, sat my table, and actually talked to my mother about protecting her family and making sure that she was able to leave wealth to her children,” Gandy said. “That did not happen.”

According to the latest Federal Reserve data, white Americans hold nearly 85% of the nation’s wealth, versus just 4.1% for Black households. Studies show that Black Americans value life insurance products and the security and wealth accumulation and transfer they represent, Gandy noted.

“One way we can directly impact the change that we’re talking about creating,” Gandy said, “specifically in the African American and diversity communities, is to do business with somebody that does not look like you over the next 12 months.”

A Tarnished History Of Race-Based Policies

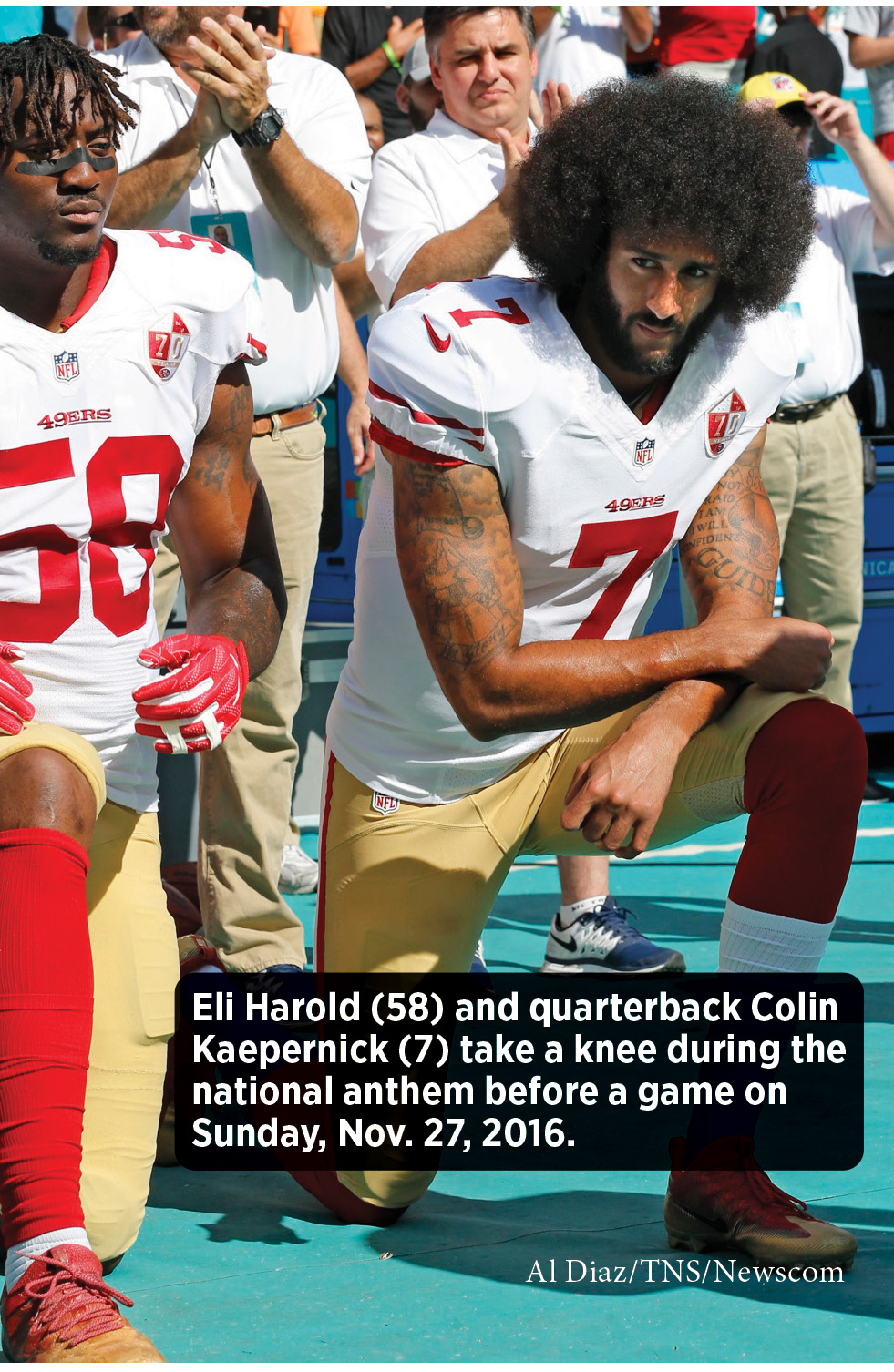

The insurance industry faced a racial reckoning of sorts following the May 25 death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police.

To the industry’s credit, many of the diversity efforts that followed were initiated from within. But some consumer activists say racial problems remain unsolved in the insurance industry. Some premium-setting algorithms lead to proxy discrimination, they claim, and the industry remains largely white.

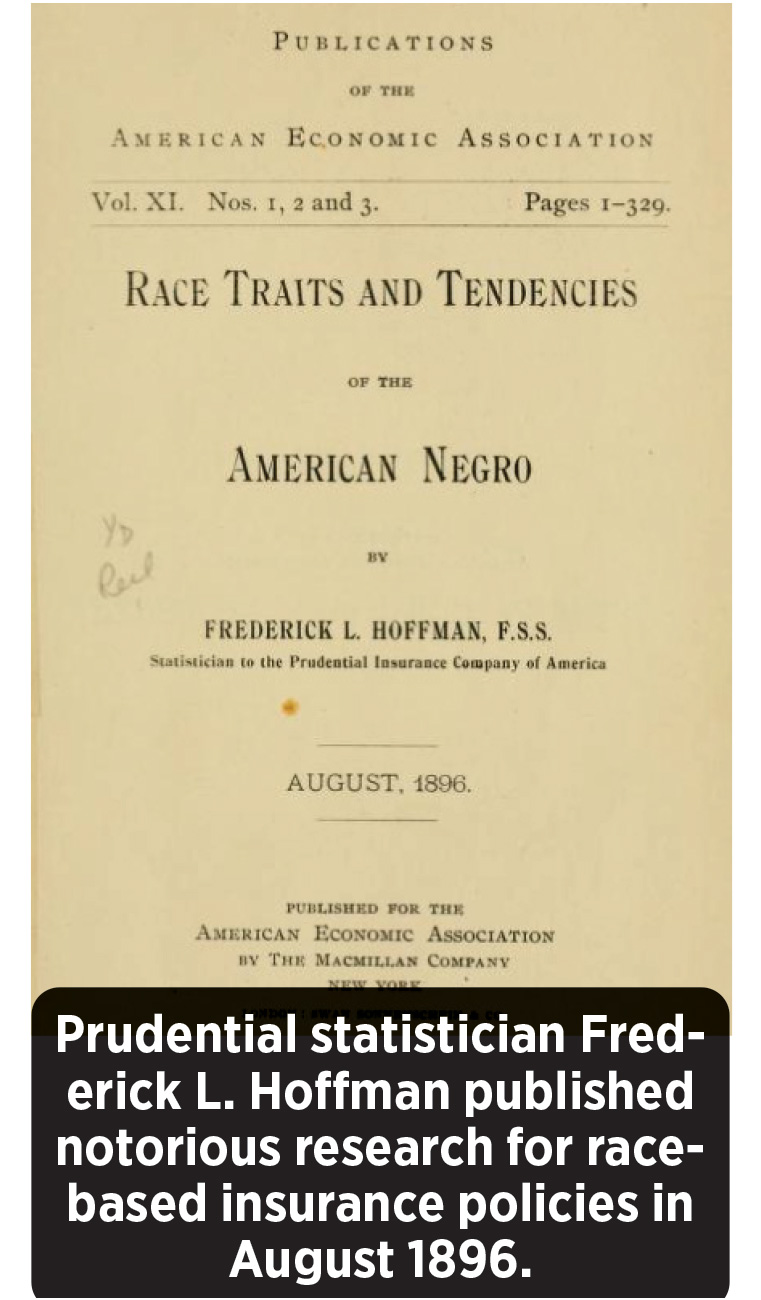

In March 1881, Prudential announced that its life insurance policies sold to Black adults would be worth one-third less than those sold to whites.

But their weekly premiums would remain the same. Prudential was one of the nation’s largest insurers at the time and its competitors, such as Metropolitan Life, quickly followed with similar inequitable policy adjustments.

And with that, life insurers entered a dark period of race-based policies based on racist and junk science. It would take more than 120 years for insurers to pay reparations to the Black community.

“Our past hasn’t always been that great, to tell the truth,” said Paul Graham, senior vice president, policy development, at the American Council of Life Insurers. Graham shared the dark history of the life insurance industry during a meeting of the Special Committee on Race and Insurance put together by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.

Early Discrimination

For several years following the Civil War, and passage of the 14th Amendment guaranteeing equal protection in 1868, Black Americans could purchase life insurance on equal terms with whites. The Black community generally purchased “burial policies” for as little as 10 cents a week, enough coverage to insure their death costs were covered.

Prudential began selling life insurance to Black Americans, many of them freed slaves, in 1875. By 1881, the insurer discovered it was paying a higher proportion of benefits to Black customers than to white customers.

Prudential founder John F. Dryden, who would later represent New Jersey in the U.S. Senate, responded with a March 1881 letter informing agents that benefits for adult Black policies would be cut by one-third. In addition, the weekly premium for infant policies was increased by five cents, although the benefits were unchanged.

Insurance agents at the time carried around two rate books, one for whites and one for Blacks, the NAIC has said. The rates for Black people were sometimes as much as 30% higher.

Without a significant body of medical evidence available on Black health and mortality, researchers relied on Civil War records, state health reports, census statistics and comparative mortality records in large cities, said John S. Haller Jr., emeritus professor in the Southern Illinois University Department of History, in a 1970 journal article.

The generally accepted, and unproven, post-Civil War view, Haller wrote, was that slavery had been “extremely healthy” for Blacks. Also, it was thought that slaves “had been immune to tuberculosis, insanity, malaria, and tropical diseases,” he added. Further medical studies found that to be false, and also confirmed that Black freedmen were at a much higher mortality risk than they were as slaves.

Time and further studies have concluded that while Blacks indeed died at a higher rate from diseases such as cholera and pneumonia, the cause is attributable to poverty, racism, poor nutrition and working conditions, and lack of proper medical care.

States Respond

The blatant discrimination of race-based policies did not go totally unchallenged. Several state legislatures passed laws forcing insurers to accept Black customers on the same terms as whites, including those of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island in the 1880s and New York, Minnesota and New Jersey in the 1890s.

In the former southern slave states, the discrimination against Black policyholders continued for decades.

“We get to 1940 and even at that time, 40% of life insurers did not sell policies to Black Americans,” Graham said. “Around 1948, there were the first adopted race-merged mortality tables, companies started pricing and selling their policies on a merged basis.”

According to The Insurance Yearbook published in 1940, another 20% of insurance companies sold life insurance to Black customers at equal rates, but did not solicit their business. And 10% accepted Black customers, but on a mortality table rated up from the American mortality experience.

Many Black entrepreneurs established life insurance companies in efforts to service minority communities. In 1939, Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal reported that there were 67 Black-owned insurance companies that survived the Great Depression. However, he called it a “poor substitute” for what was really needed — recognition from the white-owned insurance giants.

In 1964, the landmark Civil Rights Act was passed, theoretically eliminating the discriminatory practice of charging different life insurance premiums.

However, in 2000, a lawsuit was filed, alleging some existing policies from the 1960s were not changed and Black policyholders were still being charged higher premiums than whites for industrial life insurance policies.

Insurer Reparations

Ida Lee Johnson lived in Bartow, Fla., when she joined a lawsuit against Mutual Savings Life Insurance in December 1999. She only attended elementary school and was able to read “a little bit,” she said during a court deposition.

Johnson purchased an “Industrial Weekly Whole Life Policy” from Mutual Savings in 1962, when she was 37 and lived in Marietta, Ga. Her policy was designated a “colored cash” policy, with a face value of $1,000 and a weekly premium of 96 cents. Initially, the premiums were collected on a weekly basis by Mutual Savings agents.

By the time the lawsuit was amended a third time in April 2002, Johnson had paid a total of $1,884.48 in premiums for a life insurance policy that will pay death benefits of only $1,000, court documents said.

Mutual Savings, today part of the Kemper Corp., sold burial policies to both Black and white consumers, plaintiffs claimed, but maintained separate “colored cash,” “white cash,” “colored burial” and “white burial” premium structures.

A 45-year-old Black person who purchased a typical $1,000 policy from Mutual Savings would pay $1,560 more than a white person for the same amount of life insurance and accidental death benefit insurance, solely because of his race, plaintiffs said.

The Mutual Savings lawsuit was one of 16 major case settled by insurers between 2000 and 2004. Those cases covered 14.8 million policies sold by 90 insurance companies between 1900 and the 1980s.

Together, the settlements required the companies to pay more than $556 million, NBC News reported in 2004. Most of that money was paid in restitution to policyholders or their survivors, but some of it in fines, legal costs and charitable contributions.

Most insurers opted for negotiated settlements, which enabled them to avoid bad publicity and announce a break with past practices.

“The settlement addresses policies that were issued decades ago amid circumstances that are no longer prevailing today,” Robert H. Benmosche, then MetLife chairman and CEO, said after agreeing to a 2002 settlement of up to $160 million. “MetLife prides itself on providing the best products and services to all of our customers.”

‘We Cannot Ignore’

Since those settlements, efforts to eliminate racism from the insurance industry continue. For example, Texas Gov. Rick Perry signed a law making race-based insurance pricing a felony in the state.

“We stand committed to sustained partnership in the community to drive solutions to address systemic inequality. And we stand committed to fostering diversity and inclusion for our employees and the workforce.”

Industry efforts to heal wounds and address lingering racial issues are ongoing and important, officials say.

“The needless deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd have led to a movement on racial equality, that we cannot ignore,” said Ray Farmer, 2020 NAIC president, during opening remarks at the NAIC Special Session on Race and Insurance.

‘Proxy Discrimination’ Still An Issue In Insurance

Regulators and consumer advocates are fighting a different kind of race and insurance issue in 2021 — proxy discrimination.

More insurers are relying on big data to guide underwriting and set what is expected to be impartial, by-the-numbers pricing. But critics say it is anything but.

There are numerous examples of how big data algorithms discriminate against communities of color. For example, a 2018 study by Consumer Reports and ProPublica found disparities in auto insurance prices between minority and white neighborhoods that could not be explained by risk alone.

ProPublica and Consumer Reports examined auto insurance premiums and payouts in California, Illinois, Texas and Missouri, and found that insurers were charging premiums that were on average 30% higher in ZIP codes where most residents are minorities than in whiter neighborhoods with similar accident costs.

Courts have consistently ruled that “redlining” based on race is illegal. Some consumer advocates say insurers might not even know of many cases of “unintentional” discrimination if a computer algorithm is producing it.

“We don’t claim insurers are looking for ways to indirectly discriminate against communities of color,” said Birny Birnbaum, executive director of the Center for Economic Justice. “Rather, it’s about getting insurance to examine their practices for unintentional discrimination, and to change those practices within the risk-based framework of insurance.”

Birnbaum spoke during a meeting of the Special Committee on Race and Insurance formed by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.

In August, the NAIC adopted “guiding principles” for use of artificial intelligence based on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s AI principles that have been adopted by 42 countries, including the United States.

After robust discussions, regulators added a principle encouraging industry participants to take proactive steps to avoid proxy discrimination against protected classes when using AI platforms.

‘Inherently Abhorrent’

Birnbaum lobbied for stronger steps. At least one regulator, Washington Insurance Commissioner Mike Kreidler, wants more action as well.

In July, Kreidler reached out to insurance company CEOs and urged them to stand behind their recent pledges to end discrimination and racial inequities by supporting his proposal to ban the unfair practice of using credit scoring in setting prices for auto, homeowners, renters and life insurance.

“The use of credit scores in insurance is discriminatory and unjustly targets people of color, those with lower incomes, and individuals and businesses struggling during the coronavirus pandemic,” Kreidler said. “The insurance industry claims that people with lower credit scores are more likely to file future insurance claims. I believe it’s inherently abhorrent, unfair and unjust.”

Retired insurance executive Sonja Larkin-Thorne has concerns about big data, including unregulated use, lack of privacy, accuracy, transparency, and unintentional bias and discrimination.

Insurers can collect information on shopping habits, driving patterns, race, age, occupation, education, voting history, marital status, work salary and Facebook friends, she said during the NAIC summer meeting.

Federal and state regulation is needed, she said, as are laws requiring companies to unlock the data and resulting algorithms so consumers know what’s being collected and how it’s being used to underwrite and price insurance products.

ABG: Always Be Growing

Pandemic Aid Has Worked Well, Fed Says, But Missed Some People

Advisor News

- Americans increasingly worried about new tariffs, worsening inflation

- As tariffs roil market, separate ‘signal from the noise’

- Investors worried about outliving assets

- Essential insights a financial advisor needs to grow their practice

- Goldman Sachs survey identifies top threats to insurer investments

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- AM Best Comments on the Credit Ratings of Talcott Financial Group Ltd.’s Subsidiaries Following Announced Reinsurance Transaction With Japan Post Insurance Co., Ltd.

- Globe Life Inc. (NYSE: GL) is a Stock Spotlight on 4/1

- Sammons Financial Group “Goes Digital” in Annuity Transfers

- Somerset Reinsurance Announces the Appointment of Danish Iqbal as CEO

- Majesco Announces Participation in LIMRA 2025: Showcasing Cutting-Edge Innovations in Insurance Technology

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

- Thousands of Missouri construction workers with Anthem health insurance left scrambling

- Don't let death penalty turn Luigi Mangione into a martyr

- More than 5M could lose Medicaid coverage if feds impose work requirements

- Don't make Mangione a martyr

- Boston Herald: Don’t make Luigi Mangione a martyr

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News

- 2024 ModeSlavery Report (bpcc modeslavery report 2024 en final)

- Exemption Application under Investment Company Act (Form 40-APP/A)

- Annual Report 2024

- Revised Proxy Soliciting Materials (Form DEFR14A)

- Proxy Statement (Form DEF 14A)

More Life Insurance News