One Year Later: The Ones Who Prospered

As the pandemic grew, a new kind of advisor leaned in

Sibyl Slade got her start in insurance and finance because she saw the future and wanted to be the change she felt the world needed.

Slade was working at the Federal Reserve in community economic development when, in 2004, she noticed about half of the loans on the books were stated income/stated asset loans, or “liar loans.” She saw the shaky foundation undergirding the housing boom. She rang the warning bell in 2007, but it was unheard as mortgages started failing, tipping over that first domino that led to the crash of September 2008.

“I kept screaming this to my upper management, who thought, ‘Oh, well, the market will correct itself,’” Slade said, recalling her frustration.

Slade’s role at the Fed was eventually changed to a research role that was less focused on consumer protection. So, she decided to try working directly with people as a financial advisor. She left the Fed in 2014 and joined an advisory, but she became uncomfortable with the focus on proprietary products. She did not feel that she had free rein to help people with their real issues.

“They really wanted you to utilize their product, and any time you wanted to use something else that you thought benefited the client, then you had to get an exception and go through this red tape,” Slade said. “I couldn’t talk about student loan debt because we didn’t have a product to sell toward that. But I can’t sit down with young professionals and effectively work with them, asking them to redirect their income to investments when they’re looking at this student loan debt price tag and they’re asking, ‘How can I eradicate this debt?’”

She wanted a more client-focused practice that helps the underserved and others who felt as unseen as she did by the world of finance. Now, she is vice president of LifePlan Financial Advisors in Atlanta, and about 70% of her clients are people of color.

Slade is focusing on how to serve a varied clientele on their terms. Virtual meetings are essential for busy professionals. Holistic advising is healthy for families all along the financial spectrum.

She already had morphed a few times, so she was ready to pivot to a new future when it arrived abruptly a year ago as COVID-19 prompted a worldwide shutdown. Slade and other agents and advisors who have been operating outside conventional insurance and finance were ready — even if both of those industries, especially insurance, were not.

Those industries started 2020 with legacy problems, principally a failure to modernize processes. Insurance agents were still relying on dinner seminars, in-person meetings and taking it all down on paper applications. Then clients would endure as much as six weeks providing more information and submitting to medical exams.

Carriers had already made slow progress on underwriting. The pre-pandemic rule of thumb for expedited underwriting was $250,000 for term or some permanent coverage (which expanded to $500,000 to $1 million during the pandemic). Even as consumers became more tech-savvy and demanded the ease of service they were accustomed to elsewhere, the industry was slow to evolve.

Financial services were faster to take on tech and lower barriers to investors. The life insurance industry, however, was bundled up in a knot that tightened over several decades from the strands of distribution — independent distribution, to be exact.

The independent agent channel grew out of the stream of career agents who jumped to create their own practices, much like the accelerating phenomenon of brokers and advisors leaping from broker-dealers to become independent advisors. Eventually, most carriers unhooked their field forces.

In the life insurance sector, the growth of the independent channel meant no single segment could call the shots. If a carrier or a distributor required electronic processes that the agent did not like, that agent could move on to many of the other companies that were glad to take the business on paper. The agents and advisors who wanted these tools and efficiencies found few options. The more savvy ones were left to figure it out on their own.

The ones who were successful in building a different kind of practice tended to be those who were already on the outside looking in — young people, women and people of color, just to name a few.

Thriving Amid The Pandemic

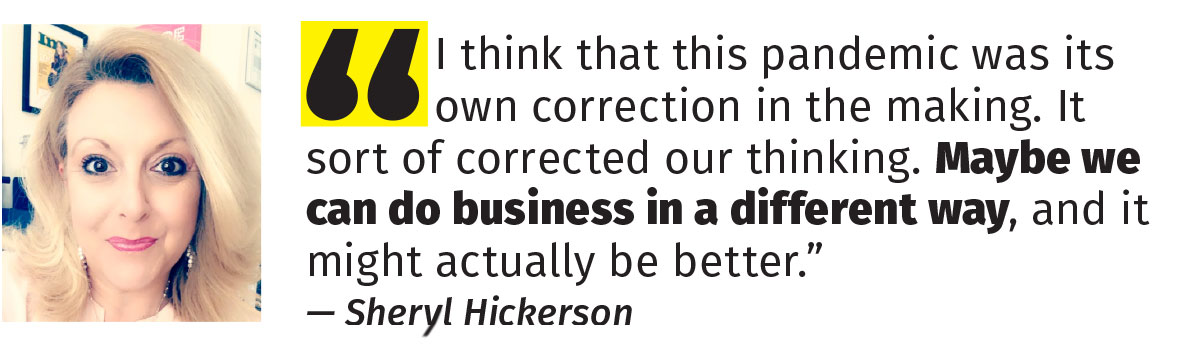

Sheryl Hickerson, founder of the support group Females and Finance, saw many of her group members thrive in the pandemic.

“I have to say the people of color, women of color, were very quick to pivot on the pulse of the pandemic,” Hickerson said. “They’re an awful lot more nimble, with the agility and the ability to be able to pivot.”

She attributed that agility to the experience of working outside the establishment within the business. As those newer advisors focused on underserved demographic groups, they developed new ways to reach and serve them. Many of those methods stood the test when COVID-19 appeared a year ago.

“I’m very encouraged,” Hickerson said. “People are saying, ‘This has to end. We have to get our people back to work,’ and I do believe that for a lot of the majority, especially retail environments, because those are our clients. But for actual insurance, risk management, investment professionals — I think that this pandemic was its own correction in the making. It sort of corrected our thinking. Maybe we can do business in a different way, and it might actually be better.”

The aging field force has been a subject of debate for the past few decades, when the average agent age has hovered around 60, give or take a few years. Change had been glacial until the pandemic, when simmering issues came to full boil.

TECHNOLOGY

The business model has been to get leads, call them and go meet the prospects. All those aspects changed to some degree, but none as much as meeting prospects and clients. The ever-present resistance to meeting a life insurance agent became a wall — people either could not meet with someone in person because of risk, or became accustomed to doing everything digitally or virtually. Agents who were not accustomed to using tech had a large learning curve to tackle in a hurry.

BIG CASE FOCUS

The life insurance industry has been criticized for focusing on the big sales rather than extending coverage to more families. By percentage of total population, fewer families in America are covered by life insurance than were at the end of World War II. But big cases need time to find, develop and underwrite. These were all difficult to do in pandemic conditions.

DIVERSITY

Life insurance sales tend to be peer to peer. Quite often, the agent and client are at about the same place in life, which makes the advisor that much more relatable. It also means that new business tends to come from this demographic, particularly because advisors will go back to their book for new business, or referrals come from peers of these clients.

The pandemic not only made it difficult to get new business from a smaller pool of older, well-off consumers who lack coverage, but it also made it apparent that the industry had a problem with inequality across the board. With the growing awareness of civil rights and equal access issues, the spotlight is on the life insurance industry for the gaps in coverage across age, race, culture and gender. It has been glaringly apparent that agents and advisors gravitate to older, wealthier men, who tend to be white. But there was also a problem with finding carriers willing to cover older people for any money, with almost all companies pulling products and raising prices.

UNDERWRITING

Underwriting has been one of the largest challenges during the pandemic. By law, medical underwriting was not possible in some areas for a period of time. But the already-existing reluctance to give fluids to get life insurance also became revulsion for some prospects. One large paramed company failed in the early months of COVID-19. Carriers that had been slowly introducing expedited underwriting to more products scrambled to raise the limit on simplified underwriting from $500,000 to $1 million.

Those who have been successful in the pandemic tended to be advisors who were already in the new normal. For example, agents who focused on term coverage and sold by telephone or virtual meetings often found more business coming their way from consumers who were suddenly very concerned about mortality and protecting their families. Those advisors tend to target a wider range of demographics, so they had more placement options with simplified underwriting.

Holistic advisors are another group that has fared well. Focusing on clients’ big picture by nature involved a wider array of products, and that client-centered focus also helped inspire trust in an uncertain time.

Variety Is The Spice Of Life (Insurance)

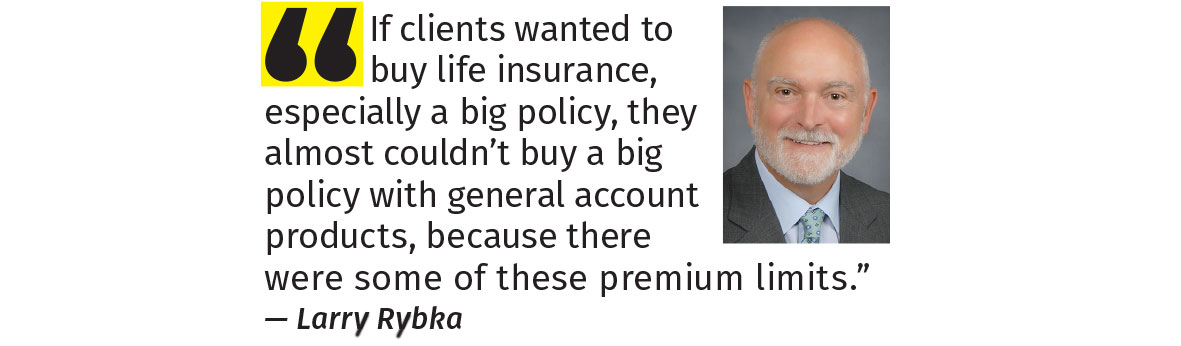

Larry Rybka was a perfect candidate to become one among the “pale, male, stale” category, but he decided early on to reshape his business, ValMark Financial, which grew from his father’s insurance practice.

His father was an innovator himself. Even though his dad was Minnesota Life’s leading agent for 21 years, he did not think advisors should be tied to one company, so he was a pioneer in going with multiple carriers.

Rybka joined his father in 1987 and later changed the direction even more by adding a broker-dealer component.

“I recognized that more and more products would be securities,” Rybka said. “I said, ‘It’s not just enough to distribute multiple fixed products.’ So, we built a business model that allows us to sell variable products, or even products that we’re paid fees on.”

He saw that the future would require less focus on product and more on planning. That required a wide array of licenses. The focus on planning also opened the door to many more products that his practice can offer. That shift served the business well from the holistic service standpoint — and it allowed the advisors to pivot when insurance companies retreated as the pandemic expanded.

“If clients wanted to buy life insurance, especially a big policy, they almost couldn’t buy a big policy with general account products, because there were some of these premium limits,” Rybka said, adding that advisors who sold only fixed life insurance products were stuck. “He couldn’t take the money. The insurance company wouldn’t take the money. So it sent more business down this variable track, which has led to an increase in business for us.”

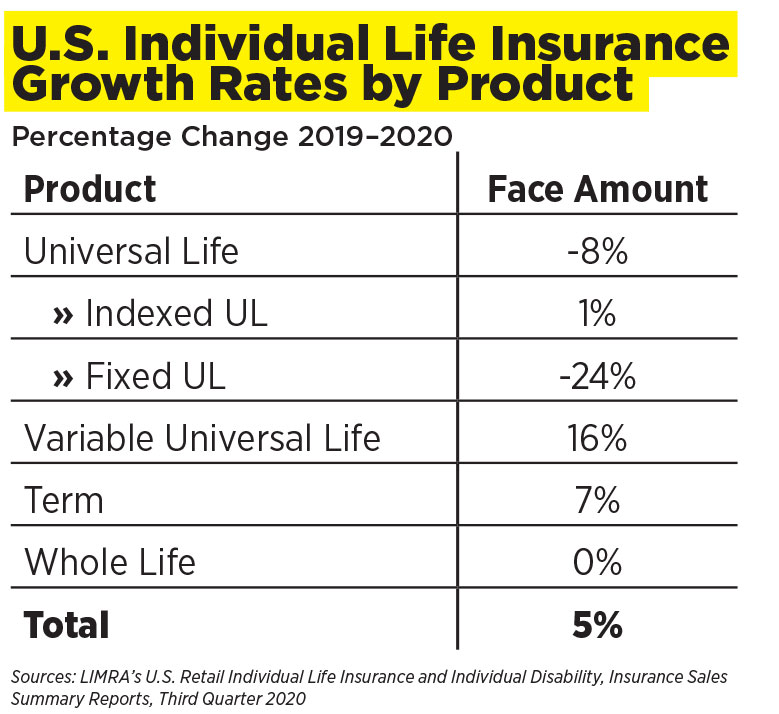

In fact, variable universal life was the only product line to have a banner year in 2020. As of the third quarter, the latest available, VUL sales were up 16% in face amount, year to date. Fixed universal life was down 24% year to date.

ValMark’s life insurance business had popped by 65% year over year as of October. The focus on variable products was a major reason for the increase, but the quick change the company was able to make during the pandemic also contributed.

Another factor that helped the company pivot was a backup plan that was already in place.

“As a broker-dealer, we had to have this emergency plan filed with FINRA in case our building blew up or caught on fire so we could still be able to operate,” Rybka said. “When the pandemic hit, within days our entire workforce was working out of their home offices, all the systems were up. We just kept right on going.”

Meanwhile, some life brokerages were struggling to fax documents to people and basically work by cellphone, Rybka said.

“They were blind for a period of time and not able to process their business because people just couldn’t take it all home and make it work,” he said.

Technology also helped with processing large cases as doctors’ offices closed. ValMark was still able to get data to the carrier.

“We can say, ‘Hey, Steve, I’m going to send you a link that has an e-signature. When you click on this, it’s going to authorize us to pull down your medical records from your client portal at Cleveland Clinic,’” Rybka said. “If you have that technology, it allows you to proceed and keep that underwriting moving.”

Another future-looking practice is Gateway Financial, which is not a broker-dealer or insurance brokerage, but an office of supervisory jurisdiction for LPL Financial. It provides back-office and tech support for about 100 advisors, said David Wood, Gateway founder and chief visionary officer.

“We didn’t plan for COVID-19, but we planned for the future of the industry,” said Wood, adding that the company had been ramping up to a virtual environment for years. “We moved to a virtual setup. We’re on the Microsoft Teams environment. We also host our own phone system on Amazon’s cloud. Some of the things that happened when we ran into this pandemic, where we had to operate differently, was that our advisors could simply pick up the phone off their desk, take it home, either plug it in or connect to their home Wi-Fi, and they operated the same as they did in an office. We just created an environment where we could work really wherever we are.”

Not only were the advisors able to work, but also they increased their efficiency by cutting travel time; they were able reach farther for clients.

“I asked one of our top advisors this morning how many appointments she had pre-COVID,” Wood said. “On a busy day she’d meet with four clients. Today, it is not uncommon to do 10 virtual meetings. She said, ‘I’ve done 10, 12 meetings a day that are literally a half an hour, and they’re back to back. And we can make a lot more connections in a much shorter period.’”

A New Kind Of Agent

Meredith Moore, CEO of Artisan Financial Strategies in Atlanta, is a New York Life agent but considers herself a financial planner first. She also works through Eagle Strategies, a registered investment advisory.

During her more than 20 years in the business, she worked to scale up her practice to the point where her typical client has either $500,000 in income, $1 million in assets or a business doing at least $5 million in revenue.

Even though Moore has a wealthy client base requiring significant life insurance coverage, she has not run into the obstacles that other agents operating in the big case realm have experienced.

That is largely because she is not dependent on commissions.

As a planner, she charges a retainer starting at $625 a month. The retainers make up only about 15% of her income, but it is the basis for the relationship with a client. Assets under management is 60% of her income and the remaining 25% is insurance.

By spanning the insurance-finance spectrum, Moore has a unique inside view of the various disciplines. One of the things she saw was that women were underserved in all the sectors.

Moore started a luncheon series where women senior leaders in Atlanta could meet and share “goals, pivots and wins.”

One of the webinars in a series she did last year also focused some of her attention on the issue.

“There’s a big problem right now and it started with the pandemic,” Moore said. “Women are coming out of the workforce right now, especially in technology. It’s going to be a really big problem in the next five to 10 years, because they’re opting right now to stay at home with everything going on, especially if they have younger kids.”

The issue fits in well with her niche of women breadwinners and their unique challenges. In 2019, the only people she could find who knew anything about those challenges were academics. So she interviewed 25 academics and ultimately wrote a white paper and built a public presentation on the subject.

“It’s called basically ‘women, money and power in relationships,’” Moore said. “I have worked with a lot of women in senior leadership. And there’s a funkier dynamic, whether we want to talk about it or not, when she makes more money than he does.”

Not only is there the difficulty in family dynamics, but also a systemic sexism that financial institutions are starting to address. Moore said she has clients in their 60s and 70s who had to get a man to co-sign for business loans. And the man did not even have to be a spouse — even a minor son could sign for the loan.

Moore combines her research and professional experience into a presentation that outlines the unique financial problems women face, along with some advice on improving the family financial dynamic. She converted these issues into speaking engagements and rolled it out to women’s employee resource groups at Fortune 500 companies, where participants can sign up for her weekly newsletter and use free financial tools.

Although Moore focuses on public outreach, it is not in the same way traditional insurance agents have done with events such as dinner seminars, where appointments are the direct objective. In fact, she finds it difficult to relate to fellow agents, and it is not only because they tend to be older white men.

“I have different interests than they do, and probably a completely different set of values, different set of goals, a very different kind of ambition,” Moore said. “Ultimately whether it’s insurance or advisory, client want to feel a connection with their advisor because of the intimacy of money.”

She also sees the disconnect with her junior advisor, who is a black millennial man. He does well in Atlanta because he does not have a lot of competition. His niche is black enterprise — and he is so busy that he has a wait list.

A New Way Forward

Sibyl Slade, the advisor in Atlanta who came out of a career with the Fed, pulled together what she has learned from a long career to create a new approach to advising.

A natural teacher, Slade gravitates to opportunities to help audiences understand the complicated world of finance. An example of that is a Facebook pop-up session that she does on Saturdays.

Slade also had a career in community service, so she formed a business services collective, consisting of a CPA, human resource consultant, small business lender, executive coach and attorney, among others. They did a series of webinars focusing on business issues such as the Paycheck Protection Program.

Many of Slade’s clients are younger professionals, so she learned to communicate with them in the way they preferred. For example, she found that those clients tended to prefer Google Meet rather than Zoom.

Those are some of the ways that Slade found to align with her clients when traditional methods were not working for her.

“Because everyone else who wants to tell you how they can make you become a successful advisor, they want to tell you about lead generation and sales funnels,” she said. “Those did nothing for me. Not that I don’t understand those concepts. That’s not the edge. You’ve got to find something to take you to the edge. Over my entire professional life, even before the Fed, I was better at problem-solving when I listened. So, that’s what I did.”

How To Stand Out And Grow

SRI: Fourth Quarter U.S. Single-Premium Pension Buy-Out Sales Jump 21%

Advisor News

- Bill that could expand access to annuities headed to the House

- Private equity, crypto and the risks retirees can’t ignore

- Will Trump accounts lead to a financial boon? Experts differ on impact

- Helping clients up the impact of their charitable giving with a DAF

- 3 tax planning strategies under One Big Beautiful Bill

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- An Application for the Trademark “EMPOWER INVESTMENTS” Has Been Filed by Great-West Life & Annuity Insurance Company: Great-West Life & Annuity Insurance Company

- Bill that could expand access to annuities headed to the House

- LTC annuities and minimizing opportunity cost

- Venerable Announces Head of Flow Reinsurance

- 3 tax planning strategies under One Big Beautiful Bill

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

Life Insurance News

- On the Move: Dec. 4, 2025

- Judge approves PHL Variable plan; could reduce benefits by up to $4.1B

- Seritage Growth Properties Makes $20 Million Loan Prepayment

- AM Best Revises Outlooks to Negative for Kansas City Life Insurance Company; Downgrades Credit Ratings of Grange Life Insurance Company; Revises Issuer Credit Rating Outlook to Negative for Old American Insurance Company

- AM Best Affirms Credit Ratings of Bao Minh Insurance Corporation

More Life Insurance News