Is popular financial advice all wrong? A Yale economist weighs in

You know the mantra – save early and consistently throughout life until retirement and enjoy your golden years. According to a Yale professor, that is all wrong – at least according to the science of economics.

That advice is the stuff of popular financial advice from non-economists, and is actually contrary to what economists would advise, according to James Choi, a Yale economist who reviewed 50 of the top financial advice books listed by Goodreads and wrote a paper about his findings.

The notion of saving early and diligently is the stuff of popular financial advice from authors such as Robert Kiyosaki of Rich Dad Poor Dad and Dave Ramsey of Total Money Makeover, but not what economists would say, Choi wrote in his paper.

Key differences

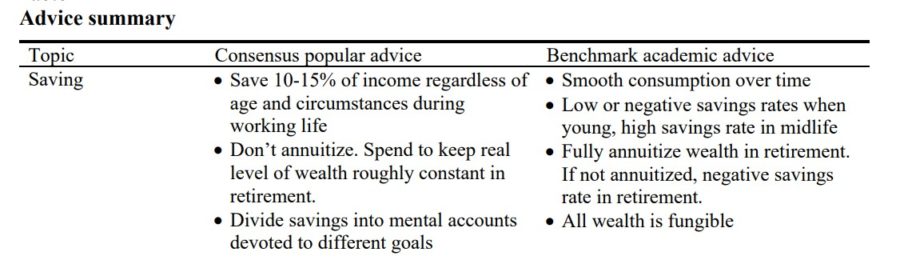

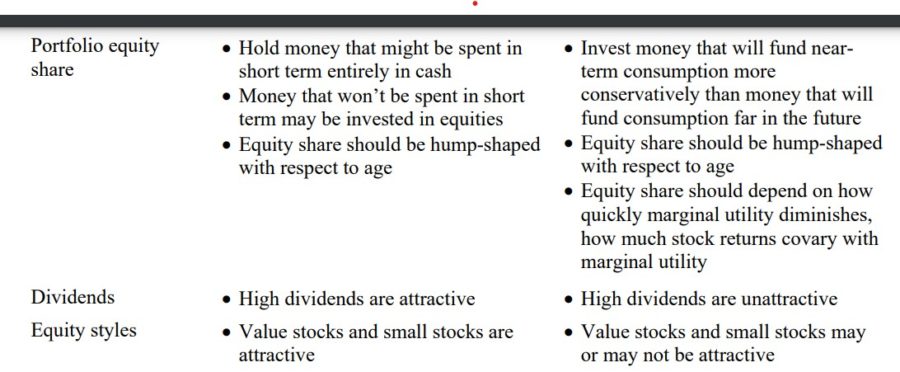

The key difference is savings vs. consumption. Economists advocate smoothing consumption, whereas popular advice advocates smoothing savings over a lifetime.

“Economists think about optimal savings rates in a way that is probably counterintuitive to the layperson,” according to the paper. “Economic theory targets an optimal consumption rate each period.”

Only one of the authors Choi reviewed made an “economist-like” observations that “the semi-responsible admonition to save 10 percent of your income essentially endorses the constant contracting and expanding of family expenditures. But surprisingly, life is easier and more enjoyable if spending always stays, on average, at a modest level.”

Authors typically call on the awesome powers of compounding when advocating consistent savings, saying that even one missed contribution would cost multiples later in life, Choi wrote.

“Of the 45 books that offer some sort of savings advice, 32 stress the importance of starting to save immediately, and 31 regale the reader about the power of compound interest,” according to the paper. “Contrary to the standard lifecycle/permanent income hypothesis model’s advice that the young should often have negative net worth, 28 books mention the need for everybody to prioritize building an emergency savings buffer of between $1,000 to two years of income. Contrary to the buffer stock model’s recommendation, popular authors advise you to continue saving at a high rate even after an adequate emergency savings fund has been established.”

But this ignores the difficulty borne early by individuals and families. Basically, people should spend when they need to and save when they can.

“Because income tends to be hump-shaped with respect to age, savings rates should on average be low or negative early in life, high in midlife, and negative during retirement.” According to the paper. “From this perspective, the common policy of making the default retirement savings plan contribution rate not depend on age is suboptimal.”

Strategies

Choi outlined typical popular finance strategies.

Savings during lifetime: As illustrated already, most of the authors advise saving early and consistently – 21 of the books advocate a savings rate the does not vary by age, with only one of them varying by amount saved. But one strategy seems to align with the economic notion of saving in the middle years, which is increasing the savings rate as income grows and saving is less painful.

Most of the books do not take Social Security into account. “Only four books recommend taking Social Security benefits into account when choosing a savings rate, despite Social Security replacing 64% of final working-life earnings for the median new beneficiary aged 64-66 in 2005.”

Mental accounting: Standard economic theory says money is money and does not earmark household savings for specific purposes, such as a savings fund for a house or a car. In popular advice, typically there is a baseline savings rate and the particular goal would require saving above that rate. But Choi admitted that even economists see the value of the strategy, citing a study that showed that labeling a savings account with a goal increases saving.

Reframing saving: Economists consider consumption the “carrier of utility” and saving the “current sacrifice.” Popular advice reframes saving as the “carrier of utility,” according to Choi, principally as a paycheck to yourself. The entrepreneur George Clason started popularizing the concept of paying yourself first 100 years ago when he started writing about it. The rule appeared in 16 of the books, basically advising that you don’t spend what you don’t see. A key observation in 18 of the books is that a significant amount that we spend has “almost no marginal activity,” Choi said.

Wealthy hand-to-mouth status: According to research, about 20% of U.S. households are “wealthy hand-to-mouth,” because they have illiquid assets, such as housing and retirement account balances, but almost no liquid assets. The problem is the individual does not have much cushion in difficult times, and might have to sell in down times. Some economists say this concept can be justified if the portfolio is producing high returns. But typically it seems to be a strategy for enforcing self-control.

Spending in retirement: Choi noted that few of the authors acknowledged the drop in spending that usually occurs in retirement. They focus on withdrawal percentages, most 4%.

The reason for limiting withdrawals is not to outlive your savings. But even though classic economics recommends annuitizing some wealth to eliminate longevity risk, only four books advise buying an annuity.

But how wrong?

Economists would have people realign their spending and savings in different periods in their lives. Principally, young people would save nothing as they build their lives and expand their savings as their earnings grew in their middle years and taper off again around retirement. This would be a dynamic vs. passive model.

But how likely are people to be dynamic as they stumble through life, caring for kids, career and the occasional catastrophe? Choi even admits in his paper that popular financial advice has two significant strengths.

“First, the recommended action is often easily computable by ordinary individuals; there is no need to solve a complex dynamic programming problem,” Choi wrote. “Second, the advice takes into account difficulties individuals have in executing a financial plan due to, say, limited motivation or emotional reactions to circumstances.”

In other words, life happens.

Steven A. Morelli is a contributing editor for InsuranceNewsNet. He has more than 25 years of experience as a reporter and editor for newspapers and magazines. He was also vice president of communications for an insurance agents’ association. Steve can be reached at [email protected].

© Entire contents copyright 2022 by InsuranceNewsNet. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reprinted without the expressed written consent from InsuranceNewsNet.

Steven A. Morelli is a contributing editor for InsuranceNewsNet. He has more than 25 years of experience as a reporter and editor for newspapers and magazines. He was also vice president of communications for an insurance agents’ association. Steve can be reached at [email protected].

Regulators, industry execs disagree on indexed-linked regulation details

Sarah Iselin looks ahead to new role leading Mass. BCBS

Advisor News

- 2026 may bring higher volatility, slower GDP growth, experts say

- Why affluent clients underuse advisor services and how to close the gap

- America’s ‘confidence recession’ in retirement

- Most Americans surveyed cut or stopped retirement savings due to the current economy

- Why you should discuss insurance with HNW clients

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- Guaranty Income Life Marks 100th Anniversary

- Delaware Life Insurance Company Launches Industry’s First Fixed Indexed Annuity with Bitcoin Exposure

- Suitability standards for life and annuities: Not as uniform as they appear

- What will 2026 bring to the life/annuity markets?

- Life and annuity sales to continue ‘pretty remarkable growth’ in 2026

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

- Hawaii lawmakers start looking into HMSA-HPH alliance plan

- EDITORIAL: More scrutiny for HMSA-HPH health care tie-up

- US vaccine guideline changes challenge clinical practice, insurance coverage

- DIFS AND MDHHS REMIND MICHIGANDERS: HEALTH INSURANCE FOR NO COST CHILDHOOD VACCINES WILL CONTINUE FOLLOWING CDC SCHEDULE CHANGES

- Illinois Medicaid program faces looming funding crisis due to federal changes

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News