Debt ceiling standoff could crash economy

As the U.S. House of Representatives heads for the door for the end of the session on Dec. 15, many eyes are turning to the ceiling.

That’s the debt ceiling and without a vote to raise or suspend it before the last vote of this Congress, the ceiling will be figuratively hanging over Democrats next year as the Republicans take the helm with an agenda that includes entitlement reform.

The limit on the national debt was raised $2.5 trillion last December to $31.4 trillion, which is expected to last until July. Incoming GOP leaders have said they will use the vote as a tool to win fiscal reforms. The ceiling does not control the amount of debt but restricts what the Treasury Department can borrow to fund the existing commitments of Congress and the administration.

Democrats have raised alarm over the prospect, largely because of the reforms Republicans want, particularly the reduction of Social Security and Medicare spending through systemic changes. Since mid-November, Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) has not said whether Congress will be putting the debt limit up for a vote by the end of Dec. 15, before the Republican-led House takes over on Jan. 3.

After the mid-term election, Pelosi on Nov. 13 said Democrats should raise the debt limit during the lame duck session, citing the Democratic wins in the Senate. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellin has also called for the vote.

But on Thursday, Pelosi would not say if a vote would be scheduled, saying that Democrats want to handle the debt ceiling in a bipartisan way. She cited other pressing concerns, particularly devising a 2023 spending bill to avert a government shutdown on Dec. 16.

House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D-Md.) also did not include the debt limit as one of the Democratic priorities for the lame duck session.

What it means

The debt ceiling was established more than 100 years ago, in 1917 with the Second Liberty Bond Act at the precipice of World War I. It was set at $11.5 billion to allow the administration borrowing flexibility. Before then, Congress had to approve each issuance of debt in a separate piece of legislation, according to the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

As World War II began in 1939, Congress pulled all government debt together under one limit, set at $45 billion, 10% above the debt at the time.

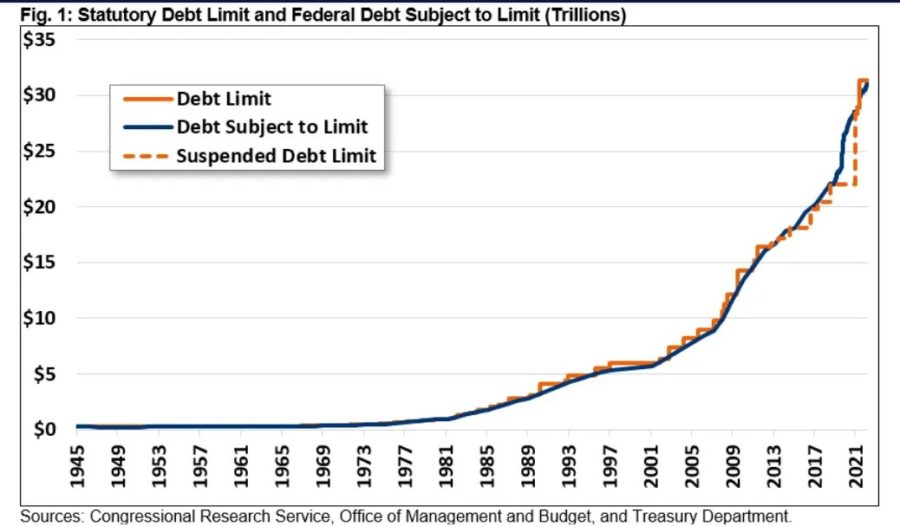

Since World War II, The debt ceiling has been modified more than 100 times. The debt itself has increased exponentially since the 1980s, when it first broke $1 trillion, then growing to $3 trillion, according to the committee. The debt doubled to $6 trillion during the ’90s, then again to $12 trillion in the 2000s. During the post-2008 crash 2010s, Congress removed the ceiling by suspending it seven times. They raised the ceiling twice in 2021, the last being to $31.4 trillion last December.

Although the debt has grown substantially and has times hit the ceiling, the United States has never defaulted on its debt. Before defaulting, the Treasury Department would be able to conserve cash by using “extraordinary measures,” which have been used by Democratic and Republican administrations.

According to the Treasury Department, those measures are: suspending sales of State and Local Government Series Treasury securities; selling current investments and suspending new ones in the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund and the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund; suspending reinvestment of the Government Securities Investment Fund; and suspending reinvestment of the Exchange Stabilization Fund.

The Treasury used some of those methods when the United States hit the debt limit last year, giving the administration cash to hold out until Dec. 16, 2021, when the debt limit was raised and default was averted.

The debt ceiling increase worked out last year is expected to tap out in July, when the whole process would start over again. The Treasury has not said when the “X date” would be -- when the government would run out of cash, forcing an unprecedented default on obligations.

Worldwide depression possible

An explainer from the House Budget Committee said a default would have severe consequences starting with skyrocketing interest rates and cascading to a worldwide depression.

“Investors would demand higher rates on future Treasury bonds, increasing the interest costs to taxpayers,” according to the explainer. “There would likely be ripple effects throughout the financial system that would increase interest rates on mortgages, student loans, car loans, credit cards, and other debt. A long impasse could prompt a financial crisis and ultimately threaten the U.S. dollar’s central role in the global financial system. All of this could trigger a severe economic depression, bringing job losses and serious hardship to millions of families in the United States and around the world."

A Moody’s Analytics study last year showed that a default would cost 6 million jobs, wipe out $15 trillion in household wealth and push unemployment up to 9%.

Social Security payments and other benefits, such as food assistance, would stop. U.S. military and federal employees would not be paid. Veterans’ pensions would lapse. The effect would reverberate for generations, according to Moody’s report.

Even a close call would roil bonds

If bondholders think they would be first in line to get paid, Moody’s said they should think again.

“While Treasury has the technical ability to pay bond investors before others, as those payments are handled by a different computer system than other government obligations, it is unclear whether the Treasury is legally able to do so,” according to the report. “Moreover, politically it seems unimaginable that bond investors would get their checks before everyone else.”

Even if the U.S. got close to default, it would destabilize financial markets, particularly bonds. The report pointed out that a debt ceiling standoff in 2013 roiled the bond market.

“Even though the Treasury ultimately did not default and interest rates quickly declined, the episode cost taxpayers an estimated nearly half-billion dollars in added interest costs, not including the costs to households and businesses that also paid higher interest rates on the funds they borrowed,” according to the report. “While these costs were modest, they were unnecessarily incurred, and they surely would have been many multiple times greater if the Treasury actually had defaulted on its debt.”

Steven A. Morelli is a contributing editor for InsuranceNewsNet. He has more than 25 years of experience as a reporter and editor for newspapers and magazines. He was also vice president of communications for an insurance agents’ association. Steve can be reached at [email protected].

© Entire contents copyright 2022 by InsuranceNewsNet. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reprinted without the expressed written consent from InsuranceNewsNet.

Steven A. Morelli is a contributing editor for InsuranceNewsNet. He has more than 25 years of experience as a reporter and editor for newspapers and magazines. He was also vice president of communications for an insurance agents’ association. Steve can be reached at [email protected].

NC regulators throw cold water on Lindberg deal to sell insurers

Bill would remove agents and brokers from burdensome Medicare rule

Advisor News

- Investor use of online brokerage accounts, new investment techniques rises

- How 831(b) plans can protect your practice from unexpected, uninsured costs

- Does a $1M make you rich? Many millionaires today don’t think so

- Implications of in-service rollovers on in-plan income adoption

- 2025 Top 5 Advisor Stories: From the ‘Age Wave’ to Gen Z angst

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- Great-West Life & Annuity Insurance Company Trademark Application for “EMPOWER BENEFIT CONSULTING SERVICES” Filed: Great-West Life & Annuity Insurance Company

- 2025 Top 5 Annuity Stories: Lawsuits, layoffs and Brighthouse sale rumors

- An Application for the Trademark “DYNAMIC RETIREMENT MANAGER” Has Been Filed by Great-West Life & Annuity Insurance Company: Great-West Life & Annuity Insurance Company

- Product understanding will drive the future of insurance

- Prudential launches FlexGuard 2.0 RILA

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

Life Insurance News

- Baby On Board

- 2025 Top 5 Life Insurance Stories: IUL takes center stage as lawsuits pile up

- Private placement securities continue to be attractive to insurers

- Inszone Insurance Services Expands Benefits Department in Michigan with Acquisition of Voyage Benefits, LLC

- Affordability pressures are reshaping pricing, products and strategy for 2026

More Life Insurance News