Video: The ‘excess mortality’ phenomenon: What does the future hold?

Editor's Note: The following is the transcript of an in-depth discussion of the phenomenon termed "excess mortality" currently facing the life insurance industry – and the nation.

Senior Editor John Hilton and reporter Doug Bailey led a discussion with the members of the Insurance Collaboration to Save Lives. ICSL is a not-for-profit group deploying targeted screening, testing and triage to identify those life insurance policyholders most at risk for sudden death or critical-care incidents. The panel includes:

- Josh Stirling, founder of ICSL.

- Teresa Winer, a life and health actuary for the state of Georgia's commissioner of insurance, and also an ICSL board member and treasurer.

- Mary Pat Campbell, vice president of insurance research at Conning and a member of the ICSL actuarial team.

- Dr. Edward Loniewski, an orthopedic surgeon with Orthopedic Regenerative Specialists at Rehabilitation Physicians and a member of the ICSL medical team.

- Steve Cyboran, ICSL product team leader.

John Hilton: I'm John Hilton, a senior editor for InsuranceNewsNet. Today, INN reporter Doug Bailey and I will be hosting a panel discussion on what has been described as the excess mortality trend that began with the COVID pandemic.

Doug Bailey: We’re all here to talk about something people don't really like to talk about much, and that's mortality. The idea for this actually started back more than a year ago, and we started going through insurance company financial reports. We saw a trend, that a lot of them reported losses due to what they called excess mortality, which means that they were paying out more settlements than they expected. To put it crudely, more people died than they had calculated or anticipated.

During the pandemic, you would expect mortality rates to rise. But what we're seeing is that while they did decline, they stayed higher than pre-pandemic levels. We want to know why, and I don’t know if we’ve got that answer yet, so that's partly what we're doing here today. What does it mean? What are the statistics? What does it mean for insurers? What does it mean for consumers? What does it mean for the medical and regulatory communities? Is this just a new normal, is this part of a cyclical event or are mortality rates now going to remain high?

At the end of last year, the head of the FDA noticed a concurrent drop in life expectancy and said that this was indeed such a catastrophe that he called for all hands on deck to try to mitigate it. He said there's a role for government, for industry, for the medical community and for consumers to play a part. We'll get underway, and we'll go right to Josh. We will get to the advocacy and goals of your organization at some point. But first, please just give us an overall picture of what the mortality situation is, what it was and what you think it's going to be. And then I'll ask you the question that I asked you the other day — are we in a crisis?

Josh Stirling: Doug, I appreciate the opportunity to be here today. I appreciate you guys reporting. I mean, not everybody's ... but actually I think it's changed. By the time you began writing about this, this was something that was an emerging story, and I think there have been a lot of major news outlets that are starting to talk about it. I guess the appropriate thing to do is say congratulations to you and your editors and your team for sort of following the news.

And I want to say — and I can talk a lot — but I'll just say a lot of us in the group came to this story from the same way — we were listening to insurance earnings reports. I used to be an insurance analyst, so this is, I wouldn't say that I do it for fun, but this is something I'm aware of.

When people start talking about excess mortality, and that's not something you ever hear in life insurance companies, not ever in my entire career as an insurance analyst, not something we ever talk about. That led to questions. I want to show you one chart to start the conversation. And this isn't my chart; this is data from USMortality.com. But it's very similar to the work I started doing, and I know Mary Pat's a world expert in using basically CDC data to be able to track mortality in all sorts of different slices.

This is age-standardized excess mortality. There's no one perfect way to calculate any of these numbers, but directionally, what this is trying to do is control for a standard population without changes in age demographics. That also adjusts for the fact that younger people don't die as often as older people do, so it's attempting to be a good apples-to-apples comparison. There may be reasons why it's not as high as it could be, but in the big picture, this is a directionally very useful way of starting this analysis.

Look at these numbers for two years. There is excess above the baseline, These were periods when we were seeing deaths that were higher than we expected. This is monthly data. In December 2020, it was 41% higher than it was supposed to be. September 2021 was a weird month for that, as it was 39% higher than it was supposed to be. But luckily in 2022, it declined. But you're still in this 10%, 12%, 11%, 14% in December 2022. These are big numbers, these are very stable. Recently, in 2023, it's been more like 6%. The data's not mature yet for the more recent months, but in January 2024, so far it's 6.2%. Just to complete the story, you look back at 2019, and these numbers were basically zero, somewhere above zero, somewhere below 2018’s.

Doug Bailey: That doesn't mean nobody was dying.

Josh Stirling: No. This is a derivative measure. This is the excess above the expected, but what it means is that the model is probably reasonable because it's sort of straddling zero. Also, that's what normal looks like. And I want to answer your question; I don't think it's been popularized yet in the media the way that people died after [the pandemic] crisis, but I think the new normal is the right concept. Obviously, we hope this number goes back to zero this year, but so far in January, it hasn't.

Last year, it was 6%. The year before that, it was 12%. Maybe we're trending down; that would be lovely. That would be a reasonable conclusion from this data set. But we're four years on from the pandemic, so it's a reasonable question. Is it a new normal? It's four years on, and as a former stock analyst who gets judged every day, I'd say we're living in the new normal now. We're just not sure how long it's going to last.

Doug Bailey: Well, Josh, how is the normal, the straight line at the bottom? How is baseline calculated?

Josh Stirling: Well, that was a forecasted trend based on the historical trends. But there are different ways to play at their website to get that, and I couldn't do it for you in real time. Basically, they do a later regression of history to say this is where it should be, and the fact is, it's pretty good at predicting 2018 and 2019. But what ended up happening is that you imagine that straight line like this. 2020 went way up here, and then 2021 was about the same, and then 2022 and then 2023, but it's still above. To your point, we've kind of elevated the baseline, so now that the baseline seems like it's 6%, but hopefully things get better. Dr. Loniewski talked about the biology, and Mary Pat and Teresa and Steve can talk about the actuarial perspectives on that, but we certainly hope it's getting better. It's just that four years on, we're still not back to where we were before.

Steve Cyboran: One thing that I'd just like to add to that is in past pandemics, you see a pull forward of mortality, and then you see a valley for the mortality that was pulled forward. That usually is the next year. We're four years on, and we haven't seen any kind of a valley, and when you see an average of a 6%, a 12% increase, there are some age groups that were still 20% last year, still 20% up. I think Mary Pat could speak to this better, but I think in particular last year that it was the younger ages, 15 to 45. Mary Pat could speak to what the real numbers are.

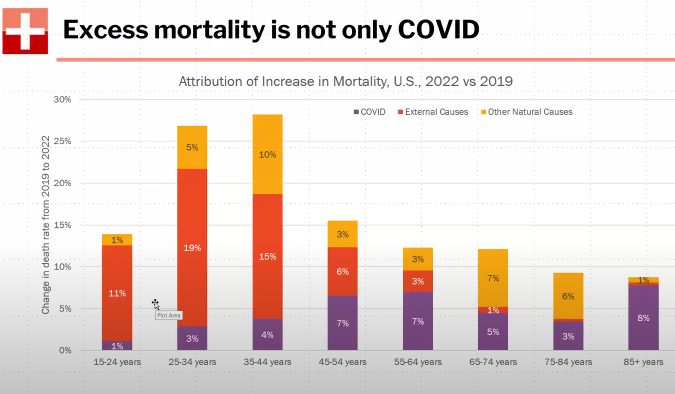

Mary Pat Campbell: This is a much simpler graph. I'm developing this for the Nashville conference, so let me explain what this is. This is the standardized 10-year age groups that the CDC gives, and this is all CDC data. I'm comparing to 2022, and this is that finalized data against 2019. I'm not doing any trending, nothing like that; this is very simple. How much did that death rate step up from 2019 to 2022? We saw, and I think we keep pounding this, that the worst relative increase in mortality has been in this group, 35 to 44 years old. Where is it coming from? You saw those huge peaks. Well, a lot of that was COVID deaths, and a lot of that was, sorry, rather old people. But now in 2022 and then into 2023 — though this is just 2022 data — the purple is the COVID, and that's going to be primarily where most of the excess mortality is for the oldest age group, 85 plus one.

Those really increased during the pandemic, and it's still heightened. That's stuff like motor vehicle accident deaths and drug overdoses, and the drug overdoses were already on a bad trend. You can see that's a large contributor. The 25-to-34-year-olds, that increased almost 20% in 2022 compared to 2019. I'm sorry, but I'm going to tell you to ignore those two bits because COVID has come down quite a bit since 2020 and 2021, when it was at the peak. External causes — motor vehicle accident deaths and drug overdoses — are affected by how much the insurance industry can influence that. A lot of it is public policy. But the yellow on the top, that's the other natural causes. That's our heart disease, diabetes, liver, kidney. We've seen all sorts of causes of death increase during the pandemic, and this is the 2022. Again, it's that 35-to-44-year-old group, they're getting everything hitting them, and that's had the worst effect.

Combined, it's an almost 30% increase in their death rate in 2022 compared to 2019. This is a huge increase that is affecting life insurers, primarily group life insurers. And it's also affecting other lines of businesses, such as disability insurance, long-term care insurance, workers' comp. I mentioned motor vehicle accident deaths — that's in the red here. Auto insurance has been affected by these increased motor vehicle accidents and deaths. This is 2022; in 2023, these other natural causes are what's contributing to that continuing to be about 6% excess mortality. It's not just COVID.

Doug Bailey: So we can't blame the phenomenon on long COVID or anything like that?

Mary Pat Campbell: Well, some of those other natural causes, maybe it is long COVID. We don't know because it's not necessarily going to be COVID on the death certificates. All of this is based on underlying cause of death, the one and only one major driver of what caused the death. There can be contributing causes of death on the death certificate, but I'm not using that in my analysis right now. There can be COVID, but long COVID is still in its infancy of being investigated.

Dr. Edward Loniewski: Definitely, depression is up, and depression leads to drugs and drinking...

Steve Cyboran: Suicide.

Dr. Edward Loniewski: Suicide.

Mary Pat Campbell: Also, the alcohol-related deaths are up quite a bit, but I'm not putting that on here. There's a lot of bad stuff in there for the external causes, and I don't like talking about this. Suicide has a very weird pattern as well.

Dr. Edward Loniewski: The external causes could be part of long COVID, since one symptom of long COVID is depression.

Mary Pat Campbell: From an insurance company point of view, all of this goes into it. I keep saying dead is dead. If you’re a life insurer, disability insurer, long-term care, whatever, it will have an impact. A death will have an impact one way or another.

The Society of Actuaries has been really on this in doing experience studies for both individual life insurance and group life insurance. Of course, they're underwritten in different ways, but they have been reflecting some of this. They have been splitting out COVID versus non-COVID impacts, and they have been finding excess mortality from non-COVID sources. That has been interesting, into 2023, even as COVID has come down.

Some of it was positing that oh, well, heart disease, maybe because COVID is causing some heart disease problems or they're not going to the doctor. We saw utilization go down quite a bit, health care utilization go down in 2020 and 2021, that people who should have weren't going to the doctor, or even older people who needed help to get to appointments; they lost their ride, perhaps. Those were some of the things they were positing, but now, as we're getting into 2023 and 2024, that can't be the explanation so much anymore.

Doug Bailey: It seems like this all would argue for a temporary outreach or effect of COVID. I mean, automobile accidents were up, suicides were up, drug addiction was up, and a lot of it was attributed to the pandemic period.

Mary Pat Campbell: We didn't really see them come down a lot during 2023. This is 2022. As Josh showed, we're still seeing persistent excess mortality from our 2023 data as well. It's really not come down a lot, so this is concerning.

Steve Cyboran: The one thing I'd just like to add is that long COVID isn't necessarily a diagnosis but more a collection of symptoms, and there are other underlying health issues that are driving that. The mortality data shows it is affecting a lot of your major systems — which Dr. Loniewski could probably speak to better — but it is affecting the circulatory system, the skin, and it's affecting cancer and a lot of other things because of what it's done to immune systems, etc.

Doug Bailey: Dr. Loniewski, have our immunity systems become more vulnerable, or do you see signs of this being a long-term effect? I also have to add that every time we write a story about this, I get inundated with letters that say they know what the cause is — it's the vaccine that's causing all this. Could you talk about that as well?

Dr. Edward Loniewski: I look at big trends. I wanted to share something with you, something I think is quite interesting, and it's basically from the same data that ICSL has here. What I did notice was that … I'm still seeing patients. I would have patients who would come in and ask me to shut the door so they could tell me about their symptoms that are unusual. I thought that was something to investigate, and luckily, I was put on this committee and started looking at this. This is Mary Pat’s diagram here that I decided to go ahead and share with my patients, and it not only shows that there's an increase in death but also an increase in disability. For the first time ever, first time ever, we've seen a decrease in our life expectancy by quite a bit, quite a bit.

You have to think about what are the causes of that, and are we done with this? Is this something that we can just say, "Oh, this is something in the past" and just shut the book on it, or is that something coming up? One of the things I had up here was about the double bump. I always like to look back at history, and in 2018, the Spanish flu and H1N1 both had a double bump. What I mean by a double bump is where you have an increase in mortality, you have a short pause and then you have another increase in mortality, usually lower than the first one, and then the pandemic is over. Well, we had the increase, but we haven't had the second bump. You have to think about why. Usually that bump comes between about eight to 10 months, and it's definitely been a lot longer. There must be something going on with our immune systems. It could be — I don't know for sure — but it could be that we all were vaccinated during the pandemic, which is not normal. I just came back from Kenya last week, and normally when you go to a country that has, say, yellow fever, you get vaccinated before you go to Kenya. Why? Because when you're in Kenya, it's not very effective to get vaccinated there. Here, in the midst of a pandemic, we all got vaccinated. That does something a little bit different to the response of the human to the virus, which extends the length of the viral infection, though maybe it's a lot lower and less deadly, but now you have this thing called a viral escape, and all those viruses that are escaping may come back to bite us at some point. Maybe.

Doug Bailey: What do you mean by viral escape?

Dr. Edward Loniewski: Let's just use the example of antibiotics. When you're given a dose of antibiotics, what does that doctor tell you all the time? Make sure you take all of them. Why? Because if you only take two days’ worth, well, then you get resistant organisms, and then they have to use a different type of antibiotic. Eventually, they run out of types of antibiotics.

What that means is that the bacteria escapes; it doesn't get killed, it escapes. It's the same thing when we artificially stimulate our immune systems to simulate a spike protein. There are certain T cells, the ones that give us that memory that says to bacteria, "Hey, I've seen you before." Those kind of escape, and we don't get fully immune to that. That's why it's always said that people who have had natural immunity — somebody who has had, say, yellow fever, or somebody who has had COVID — has a complete immune system. Newer studies have shown that natural immunity definitely is better than the immunity given by a vaccine. Now you've got these escaped viruses that are out there, and maybe they may come back and bite us and give us a second wave because it's possible we have not had that second wave.

Doug Bailey: Maybe we can get an insurance underwriting perspective here. What does this do to the calculations of trying to determine the mortality rates going forward? Who wants to take that one?

Josh Stirling: I'll take it if I can be flippant, because I'm not the underwriter or the actuary here. The problem with life insurance is you have to make these plans — most of your policies, your pricing for 30 years — in advance, and you have to make these estimates based on historical trends. For something like 500 years, mortality has been improving, so those estimates were really stable and generally going down very slowly over time. That's been a really easy trend for the insurance industry to model. What's very unclear is where that trend goes today. A couple of months back, we published a chart, where we had taken a survey at the Society of Actuaries conference, and we asked actuaries how many of them thought mortality would continue to be elevated. I think it was roughly about 80% who thought that in a couple of years, it would come down.

Someone else asked the same question the year before, and you had the same exact number of people saying, well, a couple of years out, it's going to come down. There's a part of me that feels like, again — and I'm being flippant but serious in a real way — it's very hard for life insurance to model the future around things you don't know. For those in the life insurance world, people were mispricing long-term care for 30 years. They always thought they were just right around the corner and we had just got it right, but it turns out we didn't.

And 30 years after it was done, all of a sudden, GE fires its CEO because it turns out they still have business that people didn't even know about. Again, I'm a little flippant — I'm a stock analyst, I think about big picture here, but when I look at these numbers, I see an inflection change, and now it's positive, it's positive beyond expectations. The industry wants it to come down. We hope it comes down. Our group got together because "Well, what if it doesn't, and what should we be doing right now to try to help it come down?"

Mary Pat Campbell: Right. There've actually been a few changes here. In the accounting for life insurance for GAP recently, we had it targeted, but was it targeted improvements for long-duration contracts? Once upon a time, those mortality assumptions were locked in at issue, and unless the reserves for the life insurance contracts went deficient in some way, you kept them. That was for all sorts of assumptions, but now you're supposed to keep them up to date at least annually. If there is a new normal for mortality, then those reserves will have to be updated and perhaps raised annually if it turns out the mortality is worse than you had expected. On the GE example on that long-term care, they had known about it, if I remember correctly, for over a decade or about a decade before they fixed it. They let some of the excess losses flow through as extraordinary items, I believe, until they finally recognized "Oh, by the way, we have to restate reserves."

That's a big thing. These targeted improvements in GAP were for life insurance, or actually not just life insurance but just the long-duration contracts, which cover life insurance and some other related products. This was to prevent that situation from occurring where you keep all your valuation assumptions up to date, so this had more than just the pricing and the underwriting impact. This affects how you're looking at your in-force business. Part of our argument is that what actuaries have done in the past on the life and annuity sides is say, "Let's look at these statistics, let's look at the past, and we're just modeling how it's going to go." We're passive viewers of what's going to happen versus — and Josh mentioned this — at the beginning of insurance in general, it was property and casualty fire insurance. Part of the function of the fire insurance companies, like with Ben Franklin, was to help reduce the risk, not just insure it.

They weren't just going to sit there and say, "Oh, by the way, I see all these hazards, but I'm not going to help you reduce that." I mean, they had fire engines, and you had your boss or whatever, the plaque that you put on the building to guide the insurance company’s fire brigade if a fire broke out, but also do inspections give you tips? How do you reduce that? Let's put some lightning rods on your buildings, whatever had to happen to reduce the risks. Now some of the things that we're doing, and other people should talk about this, is asking what are some cost-effective tests to identify hidden risks that they may not know about? That's one of the issues, and this is why I'm starting to look at early-onset cancer; there're a lot of people, young adults, early middle age, who are not aware of some of the health risks that they may have that lead to early death. Some of the interventions might be relatively simple. Everybody knows quit smoking, lose weight, that kind of thing, but there are others that are more subtle.

Steve Cyboran: I just want to add the impact of when somebody dies two or three years early or 10 years earlier than they should have, you've now paid out assets that were supporting your reserves, you're losing that extra 10 years of premium that they would've paid. You now have the cost of replacing that policyholder, which some of the insurers tell me could be a hundred times that first year's premium. That's a lot of impact for that insurance company. There are other factors too, but that's a huge cost.

Mary Pat Campbell: It can have a lot bigger impact at younger ages than at older ages too.

Steve Cyboran: To get to Mary Pat's point about looking at other forms of actuarial science, they all do some mitigation of enforced policyholders, whether it's property, casualty, health insurance or disability insurance, life insurance is one, if not the only, area that doesn't do much of anything to mitigate the risk of enforced policyholders. There are simple things that can be done to manage that in a cost-effective way.

Teresa Winer: That might be due to that in the past, we've always had mortality improvements. It's just been projected forward. People are questioning that now, even if it has gradually come down. It was still about half a percent to a percent a year, even for reserving.

Mary Pat Campbell: Some of that was just coasting on population tendencies with regard to reduction in smoking. That did a lot, frankly, in reducing mortality. I've mentioned that I was on the Project Oversight group for the U.S. general population experience at the Society of Actuaries, and we got that started before the pandemic started. One of the reasons we were doing that was that it was understood as more sophisticated mortality projection models were needed because mortality improvement was not uniform across ages. There were life insurance companies that found they were getting bad mortality experience, and bad mortality experience just means it was worse than you expected. It could have improved, but it improved less than you expected, and that would be bad mortality experience. That was happening in early 2018. I was seeing with heart disease that it wasn't improving like it used to. What's going on with that?

We were teasing apart trends by different age groups and by sex, and different causes of death like Alzheimer's disease and some others were actually getting worse, other than the ones that we knew about like drug overdoses — we knew about that one. But there were natural causes of death where the trend was not what we thought it had been, and it was affecting the aggregate trend. Then with the pandemic, we've found that it got exacerbated and really bad. This might be when we say new normal maybe got reset to a worse position, and the trend might not go back to where it was before.

But at the Society of Actuaries — again, I'm going to keep plugging them because they've done a lot of work — they've had a couple of research papers where they said, "Well, what is excess mortality anyway?" Should we have continued the trend, which was improving in aggregate overall? And then we have a much bigger excess mortality measure in the pandemic than what I've been showing you here, by the way. Should we do it by individual cause of death, different choices? You might make a choice, depending on what the application is in a model. My application was trying to educate the public, so I was keeping it simple, and I said, "2019 was a boring year for mortality." There wasn't anything really going on with seasonal flu, so I didn't even average prior years. In prior years, there was a really bad seasonal flu. I didn't want to include that, but others have. There are different choices to make.

Dr. Edward Loniewski: With actuaries and all the stuff that Mary Pat does and what Josh has looked at and Teresa has looked at, that's all stuff that's all, again, history. I'm on the front lines, I'm seeing patients all the time, and in my other job that I have, I'm a medical officer for a pharmaceutical company that treats cancer. I am at the end; I'm the compassionate use doctor that patients who have had cancer, have had four or five treatments, they're not getting anywhere or their cancer comes back, they come back and they petition us to use our drug that's in trial. There's a new law that was passed about the right to try and those type of things so that the patients can actually access this. When we first started that, it was maybe one or two people a month who would contact us. Now it's four or five a week. They usually have the same story. Also, in my normal practice, where I see patients face-to-face, I will tell you that there are a lot of patients who come in and have other conditions — especially blood clots, strokes — that I just didn't see before. Those will take some time to become recorded. Especially with cancer, you won't see a death for maybe four or five years, so that's going to lag behind. You had to take two aspects of this — somebody who's actually looking at the numbers from behind, and people who are looking at trends that are occurring in their day-to-day practice. My personal feeling is I think that we really haven't hit bottom. I think we're going to see another spike.

Doug Bailey: Seems like we're playing some kind of whack-a-mole with symptoms, like we got on top of smoking, maybe we got on top of diabetes, but it seems like I'm seeing statistics showing an unusual increase in things like pancreatic cancer. The other day, The Times had a story that said they're seeing an unusual increase in abdominal or colon cancer among young people, people in their late teens and 20s getting colon cancer.

Dr. Edward Loniewski: I have a good friend whose son just died of that, rapidly, rapidly. It does happen, and skin cancer too. I mean, there's a huge increase in skin cancer, but again, we're not going to see the results of that on paper until later on. Speaking of things that we can do, though, it's about our immune systems. I think they've been damaged. It's very interesting. I took lab rats, I separated them out and I isolated them, because rats need to live together. If you separate them, they get diseases, they get a lot of autoimmune diseases. They get colds, they get flu, but when you put them together, their symptoms go down. The isolation issue played a little havoc on our immune system. There are other things that were given to us, done to us, that maybe even mask wearing actually increased our risk for immune disorders, but now our immune systems are damaged.

So, what do we do to go out and fix those? Real, real basic things we discovered in that small cohort of 29 patients that we looked at, looking at their vitamin D level. I tell every single one of my patients, I was an osteoporosis expert before, go ahead, and everyone should take vitamin D, and I would say, at this point, that everyone should take a bare minimum of 5,000 international units a day. And I would actually dare to say that you should be up to around 10, 10,000 international units a day, because you need to get that vitamin D level up into the 70s, not the 30s, but into the 70s to actually affect your immune system. Vitamin D is one of those great supplements that do two things, but you really need it at 70 to affect your immune system.

Another is that you've always been told to take vitamin C, but you really want that to be in that 3,000 milligram range, and zinc 35 milligrams. Those three together will help with your immune system and help stabilize that wobbling immune system.

Doug Bailey: Well, that may bring us to what the collaborative is doing and how you got started and where you see, I guess, the weak points are that you want to try to take advantage of. What are you doing?

Josh Stirling: Well, thank you Doug. We were a bunch of insurance nerds who came together and were looking at the mortality trends, learning about how to do the analysis. We started talking to doctors, who started educating us about some of the science, and their understanding is from the front lines of what was happening. We realized there was an opportunity for the life insurance industry in particular, but generally insurers, to take — including P&C, certainly supplemental, certainly disability, certainly employee benefits — basically to take a more targeted data-driven approach to try to make a difference.

What we're doing basically is that our mission is to engage and empower global insurers to address excess mortality and save a million lives through screening, testing and triaging their at-risk members. What does that mean? In practice, we would like insurance companies to provide low-cost blood testing to be available for their members so they can get tested for what we believe are the four or five things that are most helpful to address, which are typically not things people are aware of but which a lot of times are addressable through changes in their own lifestyle, but in some cases, they require medical care or possibly require medical further investigation rather than care.

In any case, the idea would be is that you could actually prevent both a lot of short-term harms like strokes, heart attacks, pulmonary embolisms and blood clots. These things are all up right now. I think there was a congressperson just yesterday who was in the news for that kind of thing. All those are very short-term acute events, which are costly to the benefits community and terrible for employers when their employees go out, and obviously incredibly costly to life insurance companies when these people are insured lives, because these basically lead to death. But that same testing can also drive very huge impact over time through cumulative impact on longer fuses or less acute issues, like diabetes or prediabetes, like the more typical heart disease that we had to deal with before COVID, as opposed to the more acute stuff. It seems like it's a thing now.

As well as, to be honest, the immune system and a possible risk for cancer, and these are things that make a real difference in people's lives. Like Dr. Loniewski said, ultimately a lot of these things can be addressed through some supplements, which we're not in the business of selling, but you can buy them at Walmart. It's not super complicated. Usually, this is just something that people don't know about, so if we can drive a little bit of education, a little bit of guidance, use the vast resources of the insurance industry, I think we can reduce some of these sudden deaths that are driving a lot of costs and are certainly driving lots of social loss. That's the opportunity we see, and we're talking to lots of insurance companies about this. We've got employer groups that are interested. We've got a couple of national branded companies with which we're in what I would say are serious conversations; all your viewers would certainly have heard of them for sure, big television advertisers, those kinds of people as well as some global companies that are talking about deploying it in Europe or in Southeast Asia.

Doug Bailey: We tend to be a little solipsistic, and we focus on the U.S. and stuff, but this is a global phenomenon, is it not? Are there areas of the world where it's worse or areas of the world that are better that we might be able to learn from?

Dr. Edward Loniewski: Yes. Do you want to say anything, Josh?

Josh Stirling: I don't have all the answers. It's a great question. It's not something we prepared before. I will tell you, though, and I learned this from Mary Pat and others in this journey, we in some ways in the United States are among the most in need of this kind of thing because we have had poor mortality trends relative to other Western developed countries for a decade. Probably, if it wasn't for the benefit, because Mary Pat's very smart about this, if it wasn't for the benefit of smoking going down for so long in advance, it would even show as worse for a long time.

We can then talk about what might drive that and social differences and health and diet, and maybe we don't have a good health care insurance system, but we also, as a society, consume a ton of health care, maybe more than other places. There are a lot of different possible contributing factors. I don't have the answer to what it is, but I think right here might be the place in the world that would benefit the most from this effort. But I don't have to have the last word on that, for sure.

Dr. Edward Loniewski: Yes, there is a trend. I look at mortality trends across the world and different countries, and it does seem like Africa, especially Central Africa, has lower death rates, especially during the COVID pandemic. Some of the Norwegian countries also have lower rates, yet we still haven't recovered. Other countries that have also mirrored us are, like Israel, very similar to ours. We don't know the reasons for sure, but it's very interesting about COVID policies during that time.

Teresa Winer: Also in the U.S., you can see in the group study the society did that the Southeast is really bad, especially Georgia, which is one of the worst. I do think that variations by obesity and rate of diabetes and so many factors also hit minorities harder or different things that may vary by state, because I'm trying to compare red and blue states, but I personally think it's more about the demographics.

Mary Pat Campbell: Yes, we keep plugging this. I mean Teresa and I are members, we were fellows of the Society of Actuaries, and one of the dashboards that comes out of that U.S. population mortality study is by socioeconomic quintile. We categorize every single county, because the CDC data actually comes out at the county level, and then we do a socioeconomic score for each county, and then we aggregate it and make five groupings, five quintiles.

There is such an obvious difference in mortality results by socioeconomic quintile. The lowest quintile just has been having a bad mortality experience for decades, well before the pandemic and for a variety of reasons. And the fifth quintile — the top socioeconomic quintile, the richest, most educated counties — tend to have been doing a lot better, and during the pandemic, they actually did a lot better. There have been differences, and there are geographic clusters there too, just like Teresa was saying, there are some geographic differences as well.

Steve Cyboran: A lot of that, though, is lifestyle related in that ...

Mary Pat Campbell: Yes, diabetes, obesity, yes. Absolutely.

Steve Cyboran: ... and the pandemic hit those people that were in worse health a lot harder. I think that is a big contributing factor and probably what you're seeing in some of those socioeconomic and geographic data.

Mary Pat Campbell: Where that comes out is in the group life insurance experience more than the individual life insurance experience.

Steve Cyboran: Even the insurers that we've talked to that are focusing more on the high-income brackets, and they do good underwriting for a lot of these things; they weren't affected as much as some of those that were these broader insurance policies, et cetera.

Mary Pat Campbell: The middle market was more affected versus that high-net-worth, high-income group. That is correct.

Dr. Edward Loniewski: I would disagree. One point about the monetary aspect of it, I think it's a health aspect of it ...

Steve Cyboran: Yes.

Dr. Edward Loniewski: Because look at Central Africa — their yearly income is easily equal to one month's salary here. I don't know if it's that, but I do think it's — again, you remember we talked about the immune system — so diabetes and obesity definitely affect the immune system and the monocyte production and all that stuff that makes you more susceptible to mortality with COVID. I think that's more about it, and I would suggest again that everybody that's listening to this should work on your immune system.

Steve Cyboran: I completely agree. That was my point, that when you see those socioeconomic levels, those people who are making more, they're more likely to eat healthier food and be physically active, whereas those people in the lower socioeconomic levels, it is probably their lack of health and their lack of interest and ability to do some of those things that've made them more susceptible. I'm right in agreement with you there.

Teresa Winer: Obesity is tied to that in the U.S. but not in Africa, whereas you probably don't have the obese issue in the low socioeconomic levels as you do in the States.

Josh Stirling: We've talked a lot about mortality, and that's super important, but there actually also are a lot of people who are sicker. I'm wondering if you want to talk a little bit about disability.

Dr. Edward Loniewski: Yes, you mentioned that earlier. I was going to ask about that.

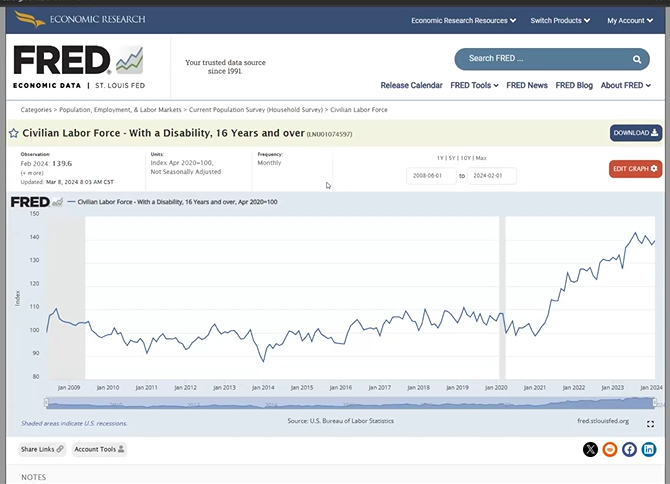

Josh Stirling: I would love to show a quick chart, in part, just for your viewers. Here we go. Again, this is a chart that anybody can go to; the Department of Labor puts it out, and the St. Louis Federal Reserve has a great website called FRED where you can get all sorts of economic indicators and cool charting tools and whatever. Obviously, I was an analyst; this is the kind of thing I would look at. But this is a survey that the Department of Labor runs every month when they also call to figure out who's employed and who's not. Every first Friday, they update these numbers, or they started doing it in 2008. We don't have surveys older than that, but they've done it for a long time now. This is not a perfect study, it doesn't have a million different variables.

But this is the total number of people over the age of 16 in the United States who answered someone from the Department of Labor calling and asking whether there is someone in your home who's disabled right now, who has a certain number of criteria that makes them disabled. It's not about whether they're getting paid or not, on disability policies or anything like that. It's not a claim, it's just a self-reported survey. What you can see, this bar is at the end of the COVID recession, that's how the software puts it on there, is at 100. You can see that actually now we're about 113, so that means 13% higher. And there was a really big increase in the number of people, and I guess this is 2021 or 2022. It really increased a lot over that period of time. And if I could just flip to what's really interesting beyond that, this is now the civilian labor force.

These are only people who are disabled but still are either working or trying to work. The first group would've included either homemakers or people who are not in the labor force, retired, or on support social services or something. This is people who are working or trying to work. Look at the scale of this chart, it's a similar thing. It's a little bit delayed but stable. But this is 139, so 39% higher. That's nuts. Then they give it to us by gender, and I don't really know what to make of this, except that this is what the number is. If you look at it for just women, in the labor force or [inaudible 00:54:11] work, it's actually 158%. It's 58% higher than it was for the pandemic, from which for about 10 years before was really stable.

I don't know exactly what these numbers mean, but I have interpreted them as a measure that they update every month as a very, very rough gauge of the level of suffering and chronic health problems that people are having in this country. Those numbers represent about 34 million people.

Dr. Edward Loniewski: That's a great point, because what do you do? You get sick first, and then you die.

Steve Cyboran: Yeah, and the mortality for these disabled lives is a much higher than for the general population by a significant factor.

Josh Stirling: On Wall Street, you would call this a leading indicator.

Steve Cyboran: Yes.

Josh Stirling: Deaths are a lagging indicator, and you use the leading indicator to predict a lagging indicator. Unfortunately, that's where we are. The idea with this group is, hey, there's a problem. We're not sure how big it's going to be, and we're not sure how long it's going to last, but we should try to address it before it works its way fully through the system, because there are people we're talking about here as well as the financial opportunity for insurers, for sure. But at the end of the day, these are our friends and family, and everybody involved in this feels we have some greater duty to try to help in some fashion, for whatever reason we're all doing that.

Steve Cyboran: In those graphs that Josh shared, it's not clear that we've hit the top. We didn't see any coming down to normalization at all, so that to me is also a disturbing trend.

Josh Stirling: If your goal is to save a million lives and your goal is to try to make the world a better place and help the insurance industry avoid what could be a train wreck in years to come, it doesn't really matter what caused this problem. What matters is we should have a Manhattan Project run by the insurance industry to try to figure out what's going on with current health and try to make it better.

Doug Bailey: I think we can wrap this up. This is really interesting and bit chilling. I think I heard the expression "good mortality experience," which I never heard before.

Mary Pat Campbell: I'm sorry. That is an expression that your ADE ratio is below a 100. Compared to what you expected, that's all they did versus bad.

Steve Cyboran: Doug, can I just add one more point? I know we talked about all these things, and there is a cost to doing this screen test triage that we talked about. We did create an impact model looking at the post-pandemic versus the pre-pandemic model, and to try to understand, well, does it make financial sense to invest in something like this? A lot of that depends on what kind of policies you have and what the level of policies are and what your population looks like, but based on some of the simple modeling we did, if your average policy size is like 200,000, you could invest probably about $100 per person to get them screened, tested and triaged, and you could break even. If you go up to 500,000, you could invest not only $100 for the screening but also maybe another $150 or so in the triage aspect of it. Depending on your policy size, you might invest more or less, and maybe it's just an incentive to get it done. Make it available and say, "Look, it's your cost, but we'll invest for some of the smaller policy side." You could use a segmented approach for your book of business to do something that makes cost-effective sense, while also enhancing the experience of those policyholders if you do it right. I wanted to make sure that didn't get missed.

Doug Bailey: That's great. Anything else?

Josh Stirling: I wonder if I might give you one piece of hopefully good news for your viewers. One of the biggest constant streams ever since we put up a website has been emails asking, "Where can I get the tests? Where can I get the tests? How can I help? I'm concerned about somebody in my family," whatever. These are the emails we get. We're going to be announcing soon, and it's going to be on our website, an ability to buy for about $150 the package of tests, and we're not doing it because we're becoming a testing company. We're not focused on making money off of this. In fact, I think we're not going to get paid at all in this process. We're really just facilitating it. We're doing this because we want to have a way to answer the emails from the real people who need help, and because we're going to go around and ask everybody who's a senior leader in the insurance industry, "If you haven't tested your team yet, why haven't you tested them? "

Because these are the people that you count on in your business, and you guys need to be the leaders. You can go figure out what you need to do for your team, and then you can do that for your customers. We're going to make it really easy, and ultimately it's for everyone's benefit. There's nothing like seeing it happen for real in your personal experience that can make a difference in your health, and then, as a leader, deciding to roll that out in a broader group. I mean, that's been what we found in our team. There are a lot of examples of people, myself included, whose health improved dramatically as a result of going through our process about a year ago, when we did our pilot.

Josh Stirling: Hopefully, that'll be soon.

Steve Cyboran: To build on that, we've also done a request for information from a lot of the insurtech, healthtech type companies so that we could identify those that have something unique or have the ability to support the broader screen test triage approach, and we're reviewing those. We're going to be meeting with those companies, and we hope to make other broader solutions available to the marketplace as well, certainly so that we can help insurance companies with custom solutions specific to their needs and their policyholders.

Dr. Edward Loniewski: I'd like to say this about being an employer. This is opening week for baseball, and a lot of times, as an employer, we would take all our employees down to the Detroit Tigers game. That would cost us about $200 per person easily. You add in drinks and everything, it’s like $250, $300. When I asked them, "What would you rather have? A Tigers game paid for or to get your health tested?" By far, nine to one wanted to get tested, because that means a lot more to them. That's their life. That's the life of their loved one.

Doug Bailey: The ultimate irony too, if you can demonstrate that it's a low-cost solution to this problem. Really, if you think about it in terms of volume, it's pretty incredible.

© Entire contents copyright 2024 by InsuranceNewsNet.com Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reprinted without the expressed written consent from InsuranceNewsNet.com.

What will the DOL rule mean for advisors?

Greg Lindberg back on trial for alleged bribery of insurance commissioner

Advisor News

- Americans increasingly worried about new tariffs, worsening inflation

- As tariffs roil market, separate ‘signal from the noise’

- Investors worried about outliving assets

- Essential insights a financial advisor needs to grow their practice

- Goldman Sachs survey identifies top threats to insurer investments

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- AM Best Comments on the Credit Ratings of Talcott Financial Group Ltd.’s Subsidiaries Following Announced Reinsurance Transaction With Japan Post Insurance Co., Ltd.

- Globe Life Inc. (NYSE: GL) is a Stock Spotlight on 4/1

- Sammons Financial Group “Goes Digital” in Annuity Transfers

- Somerset Reinsurance Announces the Appointment of Danish Iqbal as CEO

- Majesco Announces Participation in LIMRA 2025: Showcasing Cutting-Edge Innovations in Insurance Technology

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

- Mental health remains in the forefront 5 years after pandemic

- Proxy Statement (Form DEF 14A)

- Idaho Senate approves Medicaid budget

- John Oliver sued by health care boss

- Pharmacy bill passes House committee

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News

- Annual Report 2024

- Revised Proxy Soliciting Materials (Form DEFR14A)

- Proxy Statement (Form DEF 14A)

- Exemption Application under Investment Company Act (Form 40-APP/A)

- AM Best Affirms Credit Ratings of CMB Wing Lung Insurance Company Limited

More Life Insurance News