Hall of Fame, Fall of Shame

The COVID-19 pandemic is giving agents, advisors and management teams a chance to educate young athletes on the perilous nature of their careers and their finances.

Eddie George was mature enough as a high school senior to opt for another postgraduate year at Fork Union Military Academy. It made him smarter and more disciplined than most of his 18-year-old peers.

But it did not immunize him from the potential for financial disaster.

In George’s case, it appeared in the form of an unscrupulous advisor to whom the future NFL star nearly trusted his signing bonus. George had received a $2.9 million bonus with his rookie contract as the 14th pick in the 1996 NFL draft. He ultimately did not give his business to the advisor in question, who was later charged with running a Ponzi scheme.

“I didn’t know what I didn’t know,” said George, who would earn nearly $30 million over a nine-year career. “I didn’t know anything about the SEC, FINRA, Broker Check, or looking at any information on the background on this guy. I just knew that he had other famous people, other famous athletes, so if they’re with him then he must be OK.”

The experience hardened George on the ever-present financial dangers lurking to trip up young athletes who become instant millionaires. From rogue advisors to profligate spending to poor investments and planning, athletes face many threats to their wealth.

Add in the short careers — the average NFL career us about three years — and it becomes clear that financial advice and planning are crucial for professional athletes, said Shaun Melby, founder of Melby Wealth Management in Nashville, Tenn.

“More than likely, they are not as experienced with money as they would be had they reached their peak earnings later in life,” Melby said. “Because of that, they have a difficult time setting boundaries. The best advice I could give an athlete is to hire a ‘No’ person. This could be a business manager or financial advisor, but their main job is to tell people, and the athlete themselves, ‘No.’”

Some athletes respond to the opportunities and challenges money provides — Eddie George, for example. After a standout career that saw him earn four Pro Bowl trips as a running back for the Tennessee Titans and the Dallas Cowboys, George returned to school and earned an MBA from Northwestern University.

He has several business ventures, including serving as managing partner of Edward George Wealth Management Group in Nashville. A full-service registered investment advisor firm focused on high net worth clients, George endorses annuities and said his own portfolio includes one.

“It’s worked well for me,” he said. “But it just really depends on the person’s situation and their long-term goals and objectives, and how it fits their lifestyle now and how it affects them in the future.”

While he does not have any athletes as clients, yet, George rarely passes up opportunities to mentor them.

“Don’t be in such a rush to jump at every business opportunity or rush to jump into the best-looking house and live this lifestyle,” George said. “Do it slowly and methodically because the goal has to be generational wealth versus living a rich lifestyle.”

Reaching Out

Patrick Kerney tries to help young football players whenever he can, working pro bono to teach them basic financial concepts like dollar-cost averaging and how the S&P 500 can make money for them with little risk.

These are topics he is passionate about. In fact, Kerney, an 11-year veteran of the NFL, helped the league run its personal finance boot camp for players in 2015-16. Dozens of players and their wives participated in session that included “Building Generational Wealth,” “Planning and Building Your Portfolio,” and “Examining Wills, Trusts, Estate Planning.”

“It’s something I care a great deal about and have invested a lot of human capital into,” said Kerney, who heads up Kerney Insurance Agency in Greenwich, Conn. “I’d love to see more guys have the humility to learn from it, but it’s a tough argument to get them to listen to.”

The 30th pick of the first round in the 1999 NFL draft, Kerney starred as a pass-rushing defensive end for the Atlanta Falcons. In February 2007, he moved on to the Seattle Seahawks and a six-year, $39.5 million contract.

Growing up in Connecticut, Kerney said he had a strong education on the value of both work and money.

“I understood how hard it was to make eight bucks an hour,” he said. “So, when I got some money in my pocket, it was harder to pry out than from most just because I think I respected the dollar more than most guys.”

Kerney’s rookie contract paid him $5.6 million over five years. He found a mentor in the Falcons’ locker room — fellow defensive end Lester Archambeau — who helped steer him to good financial decisions.

At the end of his career, Archambeau, a Stanford graduate, walked by Kerney’s locker one day and asked the rookie if he “liked money.” Kerney answered in the affirmative, and Archambeau tossed him a copy of The Millionaire Next Door: The Surprising Secrets of America’s Wealthy.

The 1996 book by Thomas J. Stanley and William D. Danko uses research to analyze millionaires. The authors compare the behavior of those they call UAWs (Under Accumulators of Wealth) and those who are PAWs (Prodigious Accumulator of Wealth).

“It just affirmed the fact that truly wealthy people aren’t the ones running around showing it with cars and multiple homes and jewelry and all the outward material goods, but really have built an asset base that creates awesome passive income flows and a level of security that people who have high spend will never have,” Kerney said.

Following his retirement from the NFL in 2010, Kerney graduated from top-ranked Columbia Business School with an MBA in finance and studied the insurance agency model before opening his own in 2018. Kerney Insurance offers lines of commercial, personal and life insurance coverage.

‘I Want To Do Deals’

According to a 2015 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, close to 16% of the NFL players in the study who were drafted between 1996 to 2003 also filed for bankruptcy within just 12 years of retirement. Sports Illustrated surveys put the number as high as 60% for the NBA.

The financial hurdles are the same across all sports: short careers, feelings of invincibility, rogue advisors and peer pressure. Kerney saw it during his 11 years in NFL locker rooms.

“A lot of these young guys get this idea that ‘I want to do deals. I want to start a business,’” Kerney said. “I saw a hunting camp, car washes and restaurants. So not only are you in a low-probability world of starting up businesses that are going to eat away your capital, you’re also now spending your time that you can’t put toward football.”

Many advisors are using the COVID-19 pandemic to drive home financial lessons about planning and emergencies. Professional athletes can learn as well, Kerney said. Most of the young athletes know only a world of fabulous stock market gains, he noted.

One of Kerney’s financial musts is to have 12-18 months’ worth of expenses in an emergency fund. Most athletes are living off their emergency funds, or other savings, for the foreseeable pandemic-paused future. Real life is verifying the wisdom of the advice.

Otherwise, the pause gives athletes a chance to evaluate their financial situation, their goals and who is handling their money.

“Hopefully, with what’s happened with the economy and the stock market, they realize risk is real and realize that no matter how nice the suit is, a business card or the person that they’ve employed, that they’re not a magician, and that it’s time to take a harder look at that person,” Kerney said.

Fall of Shame

John Daly

Fondness for drink and a gambling addiction are the demons that combined to derail professional golfer John Daly.

A pure Southern country boy, Daly captivated sports fans when he came literally out of nowhere to win the 1991 PGA Championship. The ninth and final alternate for the tournament, Daly was a surprise late entry and drove through the night to reach the Crooked Stick Golf Club course near Indianapolis.

Despite not having played a practice round, the middling pro played well from the first tee. Daly won fans quickly with his naïve demeanor, mullet and long drives and went from an unknown to an international golf star.

Daly would go on to win another major, the British Open in 1995, and 20 times total across several different tours. At 54, he remains an active player on the PGA senior tour and won $324,000 in 2019. His career earnings across several tours is pegged at $14.2 million by Yahoo Sports.

But a true picture of Daly’s career finances is difficult due to profligate spending, which includes gambling losses that Daly estimated at a staggering $55 million in 2014. He has also been married four times.

Author of John Daly: My Life in and out of the Rough, the golfer claims he drank a fifth of Jack Daniels each day when he was 23 and on the PGA Tour. Daly battled his alcohol problem until 2008, when he claimed to have stopped drinking.

But Daly found some success in business and has likely earned much more off the course due to his outsized personality. In addition to various endorsement deals, Daly owns a golf course design company and a partnership in Loudmouth Golf clothing.

Daly has slowed down considerably in his 50s and has said he now plays only the $50 or $100 slot machines.

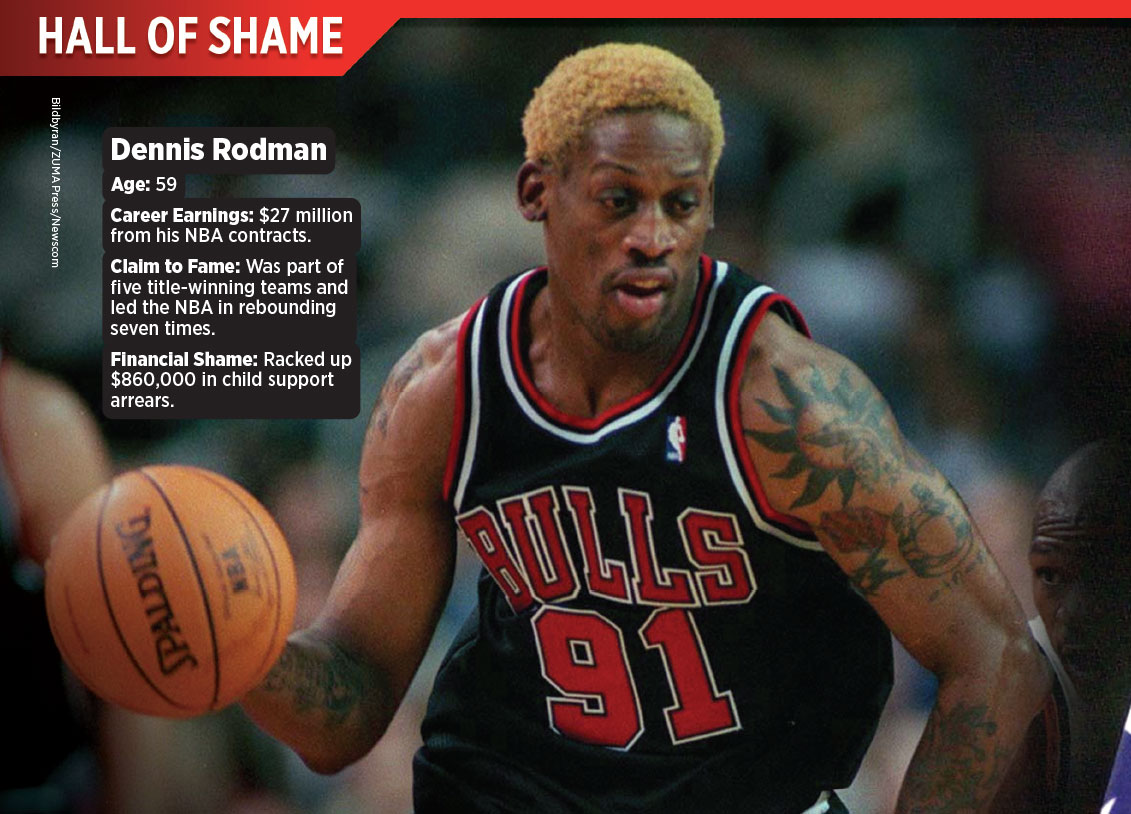

Dennis Rodman

One of the most eccentric sports figures in recent memory, Dennis Rodman made a lot of money and spent a lot of money.

A five-time NBA world champion, Rodman is best remembered for a dizzying array of hair colors while playing alongside Michael Jordan on a Chicago Bulls team that won three straight titles from 1996 to 1998.

Known as a rugged, defense-first player, Rodman led the NBA in rebounds seven years in a row and made the All-NBA Defensive First Team seven times.

Off the court, Rodman, now 59, grew up fatherless in a very poor section of Dallas. His lack of direction and discipline surfaced in a series of controversial incidents, often designed to get attention. He was frequently suspended by the NBA, once for head-butting a referee.

Rodman also wore a dress for a publicity stunt during which he claimed to be marrying himself, alleged that Madonna tried to get pregnant by him and had a nine-day marriage to model-actress Carmen Electra.

Unsurprisingly, this erratic behavior did not promote good financial decisions.

Rodman earned approximately $27 million at his peak, according to Spotrac.com. But these days, Celebrity Net Worth and other sites estimate his net worth to be about $500,000. Rodman once avoided child support payments by claiming he was “sick and broke.”

Married and divorced three times, Rodman eventually owed $860,000 in child support. He reportedly spent millions of dollars on a heavy-metal record collection that filled his $8.7 million Malibu estate.

But Rodman’s financial downfall was not all his own doing. He was one of many athletes scammed by a woman, Peggy Ann Fulford, posing as a financial advisor. Fulford, who is serving a 10-year prison sentence, gained trust by claiming to have a degree from Harvard and bragging of success on Wall Street. All lies, investigators later determined.

Marion Jones

For one brief, shining moment, Marion Jones stood atop the track universe as the fastest woman in the world. The year was 2000 and the place Sydney, Australia, where the sprinter won five gold medals at the Summer Olympics.

Also known as Marion Jones-Thompson, the Belizean-American would go on to play professional basketball for the Tulsa Shock in the WNBA during 2010-11. But the intervening decade saw Jones fall far and hard.

Jones’ problems began on Dec. 3, 2004, when Victor Conte, the founder of the BALCO lab, appeared on ABC’s “20/20” and said he had personally given Jones four different illegal performance-enhancing drugs before, during and after the 2000 Olympics.

Journalists later cited evidence and testimony from Jones’ ex-husband, C.J. Hunter, who claims to have seen Jones inject herself in the stomach with the steroids. At the time, nothing came of the charges, as Jones passed all drug tests.

But trouble was lurking. In October 2007, Jones admitted to lying to federal agents under oath about her steroid use prior to the 2000 Olympics and pleaded guilty in federal court.

Around the same time, Jones was linked to a check-counterfeiting scheme that led to criminal charges against her coach and a former boyfriend. Documents showed that a $25,000 check made out to Jones was deposited in her bank account as part of the alleged multimillion-dollar scheme.

Jones was stripped of her Olympic medals and served six months in prison in 2008 to satisfy all charges.

By that time, her financial troubles had also caught up to Jones. During her peak racing years, Jones received $70,000 to $80,000 per race, plus $1 million a year in endorsement deals from brands like Nike.

Jones was heavily in debt by 2006, the year a bank foreclosed on her $2.5 million mansion near Chapel Hill, N.C. She was also forced to sell two other properties, including her mother’s house, to raise money.

After retiring from professional sports, Jones settled down with her husband, Obadele Thompson, and their three children: Monty, Amir and Eva-Marie.

Hall of Fame

Alex Rodriguez

The popularly tagged A-Rod is one of the most talented and accomplished baseball players of the past 30 years. His post-sports career in business is on track to match or top that.

On the field, Alex Rodriguez, 44, was a polarizing player opposing fans loved to hate. Early on, much of that had to do with how easily he succeeded and the tough negotiations that led to a then-stunning 10-year, $252 million contract with the Texas Rangers in 2000.

Later, he generated controversy by dabbling in steroid use in two separate incidents. Rodriguez was suspended by Major League Baseball for the 2014 season.

When on the field, A-Rod produced eye-popping numbers. He finished with 696 home runs and 2,086 RBIs, making 14 All-Star teams and winning the Most Valuable Player award in 2003, 2005 and 2007. Were it not for the taint of steroids, he would be a cinch first-ballot Hall of Famer.

Rodriguez displayed his shrewd business acumen long before he retired following the 2016 season. Following the 2007 season, he opted out of his original monster contract and signed an even bigger 10-year, $275 million deal.

According to Spotrac, A-Rod has made more than $450 million in MLB salary to date, which included $5 million in combined 2019 deferred payments from two of his former clubs.

Rodriguez’s primary business ventures are made through A-Rod Corp., established in 2003. The firm oversees extensive investments in real estate, sports and even capital management funds. Its creative investments include Sonder, a home-rental company Rodriguez described to CNBC as “kind of a richer man’s Airbnb,” and Acorns, the micro-investing app that lets users invest their spare money.

Rodriguez is engaged to actress-singer Jennifer Lopez, forming a power duo who partner in some business ventures. According to a recent report, Lopez and Rodriguez are worth a combined $700 million.

Brian Orakpo and Michael Griffin

Ex-athletes do a lot of different things with the money and time they have upon leaving their games behind. But not many ex-football teammates partner to open a cupcake shop.

That’s exactly what Brian Orakpo and Michael Griffin did in 2018, when their Gigi’s Cupcakes franchise opened in Bee Cave, Texas. The pair — longtime teammates on the Tennessee Titans — are joined by a third friend and partner in the business, Bryan Hynson.

Gigi’s Cupcakes is a Nashville-based franchise that has more than 100 stores in 23 states. Griffin told ESPN that he and Orakpo were involved in all aspects of planning and building the business.

“We can talk football all day. But we had to learn about business,” Griffin told the network. “Learning how to start up an LLC to getting someone who is going to be working with your account to financing, just a lot of things we take for granted being professional athletes.”

The three partners described an intense three-week period working from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. learning how to open the shop, decorate, bake every cupcake they sell, be the cashier and close the shop. More time was spent learning the financial side of things.

The partners came up with a clever marketing tool in 2018 when they filmed a Microsoft Surface Pro 6 commercial about their Gigi’s franchise. Since then, they have continued to make funny YouTube videos to keep the momentum going.

“Cupcakes are a great business,” Orakpo says in their commercial.

“As long as you don’t eat the profits,” Griffin chimes in.

Nicole DeBoom

As of press deadline, professional triathlete Nicole DeBoom was seeking a partner for her women’s sports apparel firm Skirt Sports.

The business was hit hard by COVID-19, and adding a partner is just another shrewd business move for DeBoom, who spent the past 15 years building the company into a successful niche retailer.

“We’ve had a trifecta [of challenges] over the past six months,” DeBoom told The Daily Camera in Boulder, Colo.

She described those challenges as distribution partnership “setbacks” with Amazon, tariffs on imported materials to make the apparel, and COVID-19.

But challenges are nothing new for DeBoom. Growing up outside Chicago, she played every sport possible. At 16, she qualified for the Olympic trials in the 100-meter breaststroke.

But swimming was not to be her sport. After graduating from Yale with a degree in sociology, DeBoom transformed herself into a triathlete. The sport is a test of endurance, with many miles of swimming, biking and running.

She turned pro in 1999 and began winning races. But it wasn’t long before DeBoom realized she didn’t have the right training and racing clothes.

“I decided that I would turn the women’s fitness clothing market upside down and create something that had never been done before: a running skirt,” DeBoom says on her website. “My goal was to inspire and motivate myself and other women who couldn’t find what they wanted in the market.”

Skirt Sports opened for business in 2004, and DeBoom remains the CEO. Success in sport and business came quickly, with DeBoom winning the 2004 Ironman Wisconsin wearing a prototype of her first-ever running skirt.

In 2007, the company surpassed $1 million in sales, and business remains strong, even as COVID-19 brings new challenges.

“I’ve encountered obstacles big and small, caused by me or out of my control, through the ever-changing world of women’s athletics, and I continue to persevere, even when the future is impossible to predict,” DeBoom said in a January interview with Authority Magazine.

Read the full July 2020 issue online

InsuranceNewsNet Senior Editor John Hilton has covered business and other beats in more than 20 years of daily journalism. John may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @INNJohnH.

Key Regulations Come Into Focus

Hiring To Bridge The Generation Gap

Advisor News

- Study finds more households move investable assets across firms

- Could workplace benefits help solve America’s long-term care gap?

- The best way to use a tax refund? Create a holistic plan

- CFP Board appoints K. Dane Snowden as CEO

- TIAA unveils ‘policy roadmap’ to boost retirement readiness

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- $80k surrender charge at stake as Navy vet, Ameritas do battle in court

- Sammons Institutional Group® Launches Summit LadderedSM

- Protective Expands Life & Annuity Distribution with Alfa Insurance

- Annuities: A key tool in battling inflation

- Pinnacle Financial Services Launches New Agent Website, Elevating the Digital Experience for Independent Agents Nationwide

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

- National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital Describes Findings in Gastric Cancer (Incidence and risk factors for symptomatic gallstone disease after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a nationwide population-based study): Oncology – Gastric Cancer

- Reports from Stanford University School of Medicine Highlight Recent Findings in Mental Health Diseases and Conditions (PERSPECTIVE: Self-Funded Group Health Plans: A Public Mental Health Threat to Employees?): Mental Health Diseases and Conditions

- Health insurance cost increases predicted to cut millions from needed protection

- Department of Labor proposes pharmacy benefit manager fee disclosure rule

- WALKINSHAW, DUCKWORTH IMPLORE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION TO EXPAND IVF COVERAGE FOR THE MILLIONS OF HARDWORKING AMERICANS ENROLLED IN FEHB PLANS

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News