Do 2 down quarters mean recession? Not necessarily

This past quarter’s gross domestic product is expected to have decreased when it is released tomorrow, which would be the second consecutive down quarter – and that would mean we’re in a recession, right? Not necessarily.

The two-down-quarters indicator is only a rule of thumb and there is a larger handful of data to consider. Generally speaking, we won’t know for certain that we are in a recession until long after. Until then, we have indicators.

But before looking at those, we have to acknowledge that the International Monetary Fund upstaged the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis’ GDP announcement by ringing its own alarm bell Tuesday.

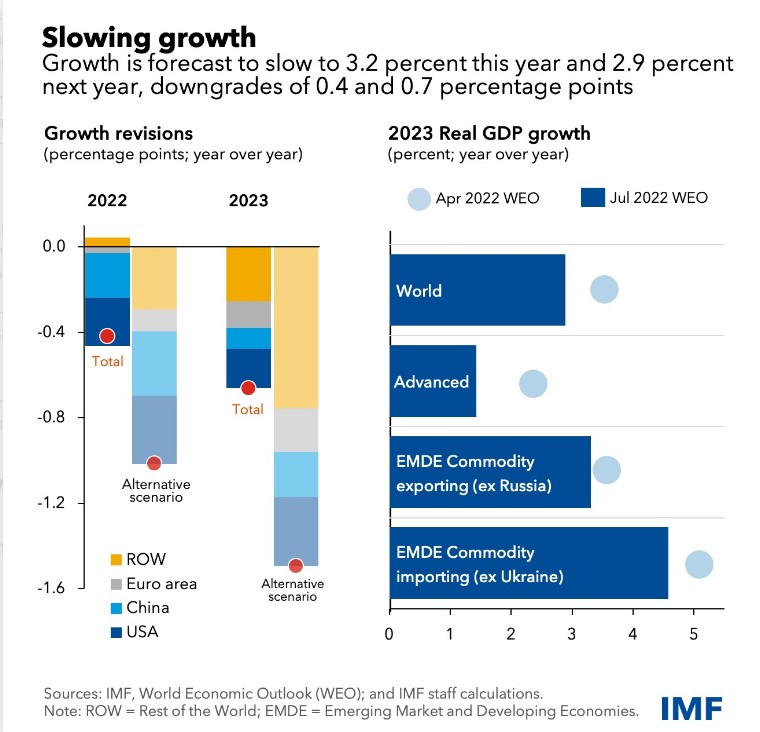

The IMF issued a fairly grim report that the world will see growth slow this year and slowing even more next year.

“Under our baseline forecast, growth slows from last year’s 6.1 percent to 3.2 percent this year and 2.9 percent next year, downgrades of 0.4 and 0.7 percentage points from April,” according to IMF’s blog. “This reflects stalling growth in the world’s three largest economies—the United States, China and the euro area—with important consequences for the global outlook.

The slump will be particularly acute in the United States, with growth slowing to 2.3% this year and 1% next year, according to the post, which enumerated the risks to the global economy.

- The war in Ukraine could lead to a sudden stop of European gas flows from Russia. [Note that Russia announced yesterday it would cut gas flow to 20% of usual capacity.]

- Inflation could remain stubbornly high if labor markets remain overly tight or inflation expectations de-anchor, or disinflation proves more costly than expected.

- Tighter global financial conditions could induce a surge in debt distress in emerging market and developing economies.

- Renewed COVID-19 outbreaks and lockdowns might further suppress China’s growth.

- Rising food and energy prices could cause widespread food insecurity and social unrest.

- Geopolitical fragmentation might impede global trade and cooperation.

Who’s running this recession?

The National Bureau of Economic Research is considered the arbiter of recessions, which it defines as the interval between a peak and a trough in economic activity. NBER has been keeping data since 1920 and started publicly pronouncing recessions in 1979.

Of course, the NBER doesn’t go to the town square and proclaim “hear ye, hear ye, the recession has commenced,” instead declaring recessions long after they are over. For example, April 2020 was the beginning of that year’s brief recession, but NBER did not declare that until 15 months later in July 2021.

“There is no fixed timing rule,” NBER said in a FAQ post. “We wait long enough so that the existence of a peak or trough is not in doubt, and until we can assign an accurate peak or trough date.”

Recessions are to NBER as pornography is to the Supreme Court: they know it when they see it. Broadly speaking, the NBER looks at three criteria: depth, diffusion and duration. The call is still subjective in a sense because even though the 2020 recession certainly did not have duration, it had a whole lot of depth and diffusion, offsetting the short duration.

Specifically, the bureau considers income, employment, inflation-adjusted personal spending, wholesale and retail sales, and factory output. But the analysts do not have any fixed rules about the information they process or how they are weighted, according to the NBER.

So, given the mystery and the delay in the NBER’s declaration, the rest of us are left to our own devices, one of which is the two-consecutive-down-quarters rule of thumb.

Whose rule is this?

The origin of the two-month rule of thumb is a bit of mystery, but the main suspect appears to be Julius Shiskin, who was the commissioner for the Bureau of Labor Statistics when he wrote an op-ed on the subject in The New York Times.

In a Dec. 1, 1974, op-ed Shiskin said even though NBER had not declared a recession, he noted that a Harris poll showed 65 percent of Americans thought the U.S. was in one, which seemed to have been confirmed by the consensus among economists and the press. It turned out the U.S. was in fact in a recession, albeit a weird one.

Shiskin had acknowledged the complexity and delay in the NBER’s process, which was then even more opaque. So he came up with some rules of thumb.

“In terms of duration — declines in real GNP [as GDP was known] for two consecutive quarters; a decline in industrial production over a six‐month period,” Shiskin wrote. “In terms of depth — A 1.5% decline in real GNP; a 15% decline nonagricultural employment; a two‐point rise in unemployment to a level of at least 6%. In terms of diffusion — A decline in nonagricultural employment in more than 75% of industries, as measured over six‐month spans, for six months or longer.”

Shiskin said these were guidelines, “particularly for those who are not experts in business cycle analysis.”

But the period he was speaking about was a confusing one, much like our current situation. A gas price shock caused by the OPEC oil embargo of 1973 triggered economic instability that contributed to rapidly rising inflation. The stock market crashed, and much like our economy, hiring was still strong.

NBER Director of Business Cycle Studies Geoffrey Moore in 1974 had said increasing employment data prevented a recession declaration even though the U.S. had three consecutive quarters of GDP contraction.

They turned out to have been in a recession between 1973 and 1975, which would reverberate from the Nixon presidency through President Jimmy Carter’s one term and to the end of President Ronald Reagan’s first term. The Federal Reserve had helped choke off the recession cycle by raising interest rates up to 20%.

In 1974, Shiskin had acknowledged in his op-ed that the economic conditions were a different animal than might need a new name.

“For this reason, it would be better to describe the economic situation today, inflation plus stagnation, by a word with one component descriptive of declining output and another descriptive of inflation,” Shiskin wrote. “The term ‘stagflation,’ now being used by many economists, meets these criteria. If further declines in output take place and employment also declines while rapid inflation persists, another term, perhaps ‘inflation‐recession,’ would be more appropriate.”

Steven A. Morelli is a contributing editor for InsuranceNewsNet. He has more than 25 years of experience as a reporter and editor for newspapers and magazines. He was also vice president of communications for an insurance agents’ association. Steve can be reached at stevenamorelli@gmail.com.

© Entire contents copyright 2022 by InsuranceNewsNet. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reprinted without the expressed written consent from InsuranceNewsNet.

Product experts: Regulators need to end ‘gamesmanship’ of IUL illustrations

Integrity Marketing Group acquires Annexus in ‘game-changer’ move

Advisor News

- Americans increasingly worried about new tariffs, worsening inflation

- As tariffs roil market, separate ‘signal from the noise’

- Investors worried about outliving assets

- Essential insights a financial advisor needs to grow their practice

- Goldman Sachs survey identifies top threats to insurer investments

More Advisor NewsAnnuity News

- AM Best Comments on the Credit Ratings of Talcott Financial Group Ltd.’s Subsidiaries Following Announced Reinsurance Transaction With Japan Post Insurance Co., Ltd.

- Globe Life Inc. (NYSE: GL) is a Stock Spotlight on 4/1

- Sammons Financial Group “Goes Digital” in Annuity Transfers

- Somerset Reinsurance Announces the Appointment of Danish Iqbal as CEO

- Majesco Announces Participation in LIMRA 2025: Showcasing Cutting-Edge Innovations in Insurance Technology

More Annuity NewsHealth/Employee Benefits News

- Thousands of Missouri construction workers with Anthem health insurance left scrambling

- Don't let death penalty turn Luigi Mangione into a martyr

- More than 5M could lose Medicaid coverage if feds impose work requirements

- Don't make Mangione a martyr

- Boston Herald: Don’t make Luigi Mangione a martyr

More Health/Employee Benefits NewsLife Insurance News

- 2024 ModeSlavery Report (bpcc modeslavery report 2024 en final)

- Exemption Application under Investment Company Act (Form 40-APP/A)

- Annual Report 2024

- Revised Proxy Soliciting Materials (Form DEFR14A)

- Proxy Statement (Form DEF 14A)

More Life Insurance News